|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Portland's relationship to Rothko

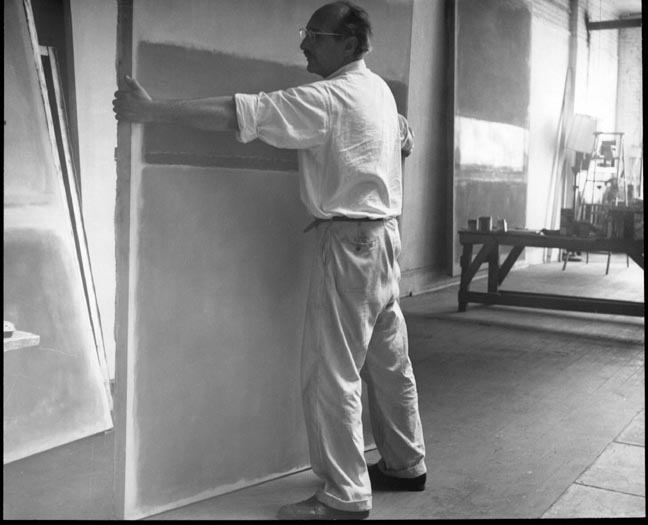

Rothko holding untitled (1954) ''I realize that historically the function of painting large pictures is something very grandiose and pompous. . . .The reason I paint them however. . . is precisely because I want to be intimate and human.'' Mark Rothko 1951 To say that Mark Rothko haunts Portland's collective civic psyche is perhaps an overstatement but there is a lot of evidence to the contrary (especially if one is sensitive to such things). This is partly because Portland as a city has bucked the predominant wisdom of the second half of the 20th century (we are pro approachable scale, anti corporate greed), just as its most famous son was. Portland is a city of shopkeepers rather than corporations as well as parks and public transportation, three things Rothko was also quite fond of. Rothko worked for his uncle, a shopkeeper and he painted subways, bridges and aggregate streets full of the masses. In short he was interested in the machine of civilization but sought a personal response amidst the modern impersonal grind. Markus Rothkowitz as he was first known was a driven, intense young man who worked hard selling newspapers beneath the Burnside bridge while cutting his intellectual teeth amongst Portland's Jewish community from age 10-18. He wrote forcefully for workers rights for the school paper at Lincoln High School (Now Shattuck Hall at Portland State University) and was even an advocate for women's rights to contraception. Rothko was above all else a humanist, driven by morals and superego more than the egotistical aim of being a great painter.  A stairway at Rothko's old High School So some may still wonder, why does Portland care so much about Mark Rothko? Certainly few artists today share any of his goals. In fact, my answer is almost too simplistic, his life's work constitutes the highest standard of cultural excellence by which we measure ourselves, yet ironically do not regularly have major examples available on display from which to do make first hand assessments. This has deep and abiding consequences since Portland has undergone a cultural renaissance over the past decade and a half, one in which visual artists have been perhaps the most emblematic. Yes music and food are also big players but it's the visual arts, which challenge Portland philosophically as a civic gadfly. When I first moved here nearly 12 years ago all I heard from long time resident's was, "Nothing ever happens here." I'd reply, "Mark Rothko." Then they'd say, "He left and didn't like Portland." My next response was always, "in the 1920's and 30's ambitious people had to leave and go to New York or Paris, surely you cant fault him for that... and his problems with Portland stemmed mostly with his family having a hard time understanding him choosing an artist's career during the Great Depression... he did have his first major solo show here, cut his intellectual teeth in the Jewish intellectual community while at Lincoln High and actually did paint quite a few pictures of Portland." Later in 2009 fellow PORT writer Arcy Douglass wrote the definitive report on Rothko's time here, debunking his lack of connection to Portland once and for all. As a Russian immigrant who lost his father immediately upon settling here it's pretty impossible to miss how that moment defined his life here and eventual decision to paint what he felt was a sense of the profound and tragedy in his late works. Perhaps the Rothko fascination stemmed from the simple fact that Portland was not telling its own histories and taking credit where due on the most basic level. Rothko's work is undeniably great and Portland played a crucial role in the way he wanted to make vast, yet intensely personally relatable paintings... if anything that humanistic scale as a moral thread is the one thing Portland and Rothko share at their core. In other words the roots of their greatness display a moral kinship to Portland's civic nature and spaces. Thus, the Rothko show at the Portland Art Museum was absolutely necessary, since a majority of Portlanders (some accomplished artists) were not even aware he grew up here.

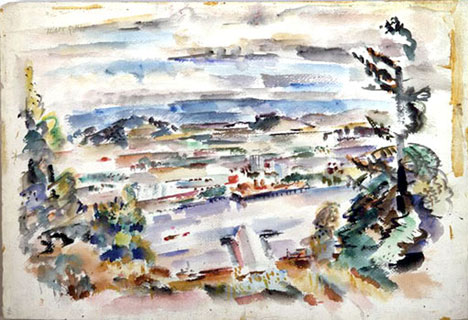

Untitled watercolor of Portland from the late 1920's. Image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art. So no Rothko's late paintings are not anything so literal as representations of Portland's moody sometimes profoundly colorful skies... but I'd say it's rather undeniable that growing up here as an intense and somewhat alienated youth and later returning to paint those skies repeatedly in the 1920's and 30's certainly gave him a sensitivity for the infinite yet up close depth effects that one finds in the later mature works. Rothko still needed to arrive at the ideas that would allow him to pain like that. You can see this quite clearly in the retrospective with early paintings like City Phantasy. The obviously New York City buildings are like scaffoldings that set up geometric volumes and the people and sky depicted are like dematerializing apparitions. He did this with countless landscapes as well. Trees and bridges set up the framing devices and the skies and landscape seem to meld... it doesn't work all that well. In 1946-1949 the same scaffolding composition undergoes a transformation and buildings, trees earth and sky all dissolve into color. By 1950 we have the Rothko paintings we know him for. The fact is that losing his father and falling in with the vibrant Jewish intellectual community were perhaps the two most crucial things to have happened to Rothko while here. Perhaps it's a missed opportunity that the Oregon Historical Society doesn't have a show based on Rothko's early days in Portland but there is time for that, especially since the PAM retrospective doesn't have a single painting of Portland in it (most of those landscapes are minor watercolors and this retrospective was already had numerous earlier even "student" level works, which is nice but you dont want to overdo it). A show fleshing out the people and places Rothko haunted would be eye opening but not entirely art centered like the Rothko retrospective at PAM. What about the retrospective? Well it is handsome and tells the mainline story without many surprises and PORT will discuss specific works in the show as it progresses. Instead, what I want to present is a cross section of reactions from artists and other preeminentPortlanders to Rothko's work. It is interesting how everyone seems to have been touched deeply, whether or not they are a huge fan: “I was into photography when I was younger and he was one of the artists that helped me see the world differently. I also appreciate how he came to Portland as a non-English speaking immigrant and went on to influence American culture so very much.” -Sam Adams (Mayor of Portland) "I consider Claude Monet, Vermeer and Rothko- the three greatest colorists , and light/ space painters of all time. Rothko's mature art is overflowing with poignant emotional power- a bit like a J.S. Bach organ chord held for eternity........ Rothko's work influences me everyday because of his profound understanding of the power of music..- after all he wanted his paintings to have the poignancy of Beethoven's 5th symphony"- Tom Cramer (Artist) "Many of the Portland artists I know whose works are as divergent as landscape painting and social practice hold Rothko's paintings as an example of the emotional timbre we would like to convey. There is this lush beauty and the shambles of human action spread across a field. I think Rothko's work thrums a chord of the sustained anxiety we feel. Seeing these works makes it somehow permissible to regard that feeling for awhile, temporarily relieving us of the duty to the jokes we were about to tell". - Eva Speer (Artist) "The experience of standing before a Rothko painting reminds me of TS Eliot's idea that authentic expression works first at the level of intuition and emotion. As Eliot says, 'Genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.' And so for Rothko." -Tom Manley (President PNCA) "While always enjoying a Rothko every time I saw one, he was not on my Heavy list. Then when I had the Crow's Shadow residency last year, Rothko came up when we looked at the rainbow roll of ink necessary for my prints. Those color stories and how they mesh and bleed are the foundation of the work. Everyone said it looked like a Rothko. I made 4 different prints and every time, he came up. For me the residency was an ultimate Oregon art experience - for too many reasons to get into here. That Rothko should keep coming up, it probably means something." -Eva Lake (Artist) When I was a graduate student in the painting department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago I regularly visited Rothko's Untitled (Painting) 1953-54 in the permanent collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. It was then that I understood the power of his work to conjure presence unequivocally with his signature color-field compositions by lavishing the surface of his paintings with nuanced silhouettes and irregular edges. That Rothko was shaped in Portland just sweetens the hometown pride and that he attended the Museum School represents a prestigious accomplishment for the institution and its faculty. Rothko stretched his figures to the margins of the picture plane without irony. His canvases each have a gravity that draw you in with their pallette and hold you with mesmerizing applications of pigment. Brushed on or into the canvas his compositions are specters. The exhibit is a great accomplishment for Bruce Gunther and PAM but above all an opportunity to study Rothko's development as an artist up close, face to face. - Victor Maldonado (Artist) "Every time we would go to Houston, we had a ritual -- before we went to the Menil Collection we would stop by the Rothko Chapel. I remember being there one morning under a dark overcast sky. We went to sit in the space and I started staring at the large triptych opposite the entrance. Because the light was low, I had one of the most intense experiences I have ever had with a painting. As I was watching the painting and as the light was changing in the room, presumably because of clouds masking the sun, the surface of the paintings started to slowly recede. Rather than paintings, they became windows opening into vast infinite space without scale or light. To quote those who write about the Sublime, I found myself face to face with the void. It was extraordinary. I was both in the Chapel and outside of it and because of the nature of the contemplation of the Chapel, I felt like I was caught between two worlds. Like Shrodinger’s cat, I was both here and there, between the living and the dead. As I was confronted with this void, I would wonder if that is what Rothko is showing, that after life there is nothing, just space, infinity, the void. Whether one would agree with Rothko’s point of view, it is an extraordinary statement to make, and not just to tell us about, but to show us, so that we could see what it was like for ourselves. It was an experience that I will never forget. I just did not know that painting a could do that. It was an experience beyond form or color or aesthetics or composition or any of the other things that we are taught about what painting should be. Nothing else mattered. It was an experience about being human and what it means to be alive. We went back to the Chapel in the afternoon when there was more light and the paintings were closed, just surfaces. - Arcy Douglass (Artist and PORT Contributor) Posted by Jeff Jahn on February 29, 2012 at 6:32 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |