|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Rothko's Portland Rothko's Portland

Portland marked the end of a long journey. It was a place that this family, like most immigrants, believed that their hard work would pay off and they could start anew. The Rothkowitzes were not alone in Portland. Jacob's brother, Samuel Weinstein, was already here and owned a successful wholesale clothing business called N & S Weinstein. The Weinsteins were important to the Rothkowitzes on both the West and East coasts. When Kate, Sonia and Mark arrived in Brooklyn, their first stop was to visit the Weinsteins in New Haven, Connecticut. It must have been a way for them to recharge their batteries after the long boat trip across the Atlantic and enjoy the comfort of family in an otherwise unfamiliar land.

When the Rothkowitzes were finally reunited in 1913, Samuel Weinstein had built a wooden, two-story house for the family at 834 Front Street in Southeast Portland. In my research, I found a photo of 832 Front Street from the 1940s showing that the house is not a single-family residence, but actually a duplex with 834 Front Street being the other half of the house. Perhaps the thinking was that the Rothkowitzes could live in one side of the house, and the other side of the house could be rented out. Starting a new life in Portland Mark's first months here must have been difficult. In September 1913, literally just a few weeks after arriving in the United States, he was enrolled in third grade at the Failing School, even though he was eleven years old because he did not speak English. Everything must have seemed strange and unfamiliar. For Mark, Portland was a place with a new language spoken by a different kind of people with their own traditions. Did the experience of being an eleven year old in a class of third graders have an isolating effect on him? Although he was described as being self-reliant and precocious, his first months here must have been an extremely trying time for a young boy.

On the plus side, at least the Rothkowitz family by 1913 was all together again and everyone was trying their best to make the most of the opportunity for a new life in Portland. His father Jacob who was a pharmacist by trade owned The Old World Drug Store and Ice Creamery. I suppose that you could say it was full service and he was going to help you feel better one way or another. It was very difficult to find any mention of Jacob in any of the Portland Directories and I could not find a reference to the Old World Drug Store either. Even at 834 Front Street, it was Albert listed in the city directory and not Jacob. I wonder if Jacob also felt uncomfortable speaking English at the time and so the people making the directories were sent to his sons, Albert or Morris. I did find a listing in 1915 of Weinstein Ice Cream and Confectionary at 709 1 st which would have been only a few blocks from the Rothkowitz’s house at the time of 834 Front Street. Weinstein was a relatively common last name in Portland at the time so there may or may not have been any connection at all. To put some perspective to what Portland was like in 1914, one of the big events was a large and well-publicized lecture by Helen Keller, who describes her ideal life in an article in the Oregonian: "I believe in work," she said, "but not too much. My idea of an ideal for human life is not too much labor, enough money to live happily, pay one's debts and help a neighbor once in a while."

By comparison, the Rothkowitzes lived on the edges of Portland, while the wealthier Weinsteins were able to live much closer in. Mark's other older brother Morris (or Mish) was a pharmacist like Jacob and opened his own drugstore called J M Ricen and was located a 315 First Avenue, a few blocks from the Rothkowitz residence under the old street numbering system, but still relatively far out in Southwest Portland.

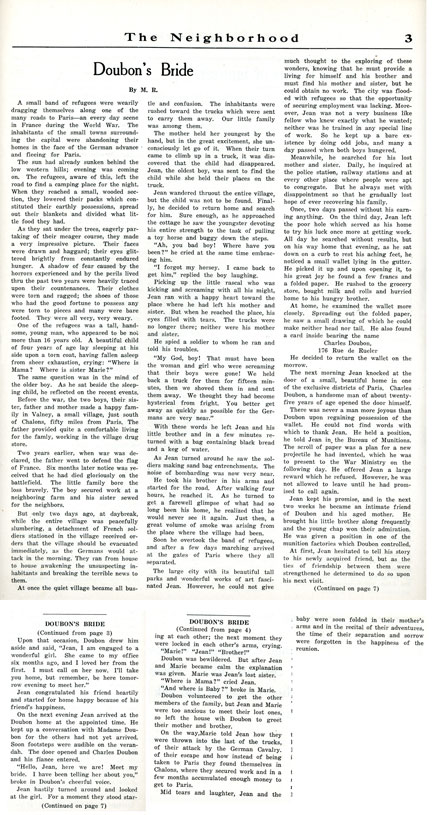

Life for the Rothkowitzes changed dramatically when Jacob passed away on March 27, 1914 of colon cancer, only seven months after Mark's arrival in Portland. The Oregonian, March 28, 1914, pg. 13: DIED ROTHKOVITZ-At his late residence, 834 Front St., March 27. Jacob Rothkovitz age 55 years. Announcement of funeral later. I could never find the funeral announcement. It is hard to overstate how difficult this must have been for the Rothkowitz family. They were barely getting settled in a new city, in a new country with a new language and most likely struggling to make ends meet, and then tragedy strikes. In later years, when Rothko tells people that the most important thing in painting is death, I can't help but think that in some way he is talking about his father. I do not think that there could have been a more painful experience for a young son. Everything that they wanted from their new lives in Portland. Gone. All of the family's dreams for a good future all together. Gone. They had to start over once again and it would be difficult for everybody. In February 1920, Mark wrote a short story called "Doubon's Bride" for The Neighborhood newsletter about refugees trying to make their way to Paris. One of his characters loses his father, who happens to be a pharmacist, at an early age. I believe hat that the story is at least in part auto-biographical. That might have been inevitable for someone that is a Junior in High School because at sixteen you write what you know, what your experience is. Doubon’s Bride is displayed and reprinted at the bottom of this post because I think it is very revealing of Rothko's mindset as prepares to graduate from High School and leave Portland. He describes the experience in the story as: The father provided quite a comfortable living for the family, working in the family drug store. Two years earlier, when war was declared, the father went to defend the flag of France. Six months later notice was received that he died gloriously on the battlefield. The little family bore the loss bravely. Was Jacob the hero in young Mark's mind? It is a strange juxtaposition of the real father dying of cancer at home and the imagined father dying gloriously in battle fighting the Germans. The funeral was arranged by Jacob's brother Samuel and he was buried at Ahavai Shalom Synagogue Cemetery on March 29, 1914. Jacob is buried in Section 128 and 34 years later he would be joined by Kate, his wife and Mark's mother, in an adjacent plot.

Even years later as a successful artist in New York, he is still haunted by the death of his father. Dr. Albert Grokest relates his conversations with Rothko in the late 1950s: What impressed me about Mark Rothko and his distrust was his referrals to his father's departure from Dvinsk. That bothered him a great deal and he would make references to it without giving specifics except that he was very much upset by it. Once Rothko and his mother and brothers and sister came here to the States to Portland and were all united with his father, the next thing his father does is die ... And he made reference to that as a terrible experience. A father's death is not something that you get over, and it would always be intertwined with his mixed emotions about Portland. In a lecture at the Pratt Institute in 1958, he said: The recipe of a work of art - its ingredients - how to make it - the formula: 2. Sensuality. Our basis of being concrete about the world. It is a lustful relationship to things that exist. 3. Tension. Either conflict or curbed desire. 4. Irony. This is a modern ingredient - the self effacement and examination by which a man for an instant can go on to something else. 5. Wit and play ... for the human element. 6. The ephemeral and chance ... for the human element. 7. Hope. 10 percent to make the tragic concept more endurable. I measure these ingredients very carefully when I make a picture. It is always the form that follows these elements and the picture results from the proportions of these elements.

While at Lincoln High, Rothko worked in the shipping department of Sam and Nate Weinstein's New York Outfitting Company. "At times," said Ed Weinstein, "Mark would occupy himself by drawing and sketching on the store wrapping paper." One day Rothko was discovered drawing by his Uncle Nate, who "shook his head and observed, 'Marcus, why are you wasting your time? You will never be able to earn a living that way.'"

A prominent man, the head of a well-known educational institution, made the following remark while addressing an assembly of high school students: "If I could conscientiously say that every person graduated from this school has, during his course, acquired the ability to observe, think about, and discuss any current social topic of interest and important with at least a moderate degree of intelligence, I should consider myself very fortunate; I could then say that the school is an acknowledged success. By this, I do not mean to minimize in your estimation the importance of any study, but I do wish to emphasize the great importance of intelligent discussion." Rothko then goes on to add: "The wisdom of the statement cannot be overestimated." And "The ability to think clearly and to set our thoughts in convincing order is always useful, is always a necessity, no matter what walk of life we choose as our own." And "If we have the power of intelligent thinking and expression, we shall not fall prey to the smooth tongues of politicians or self-seeking economists." This is pretty serious stuff if you remember its context is the equivalent of a high school newspaper. There is a surprising rigor and discipline in Rothko's early writings and he is asking a lot of his peers. But Rothko was a complete person, and he was often more than one thing. In the Cardinal 45 Who's Who section, Rothko is in a play called Alphonse and Gaston with another student named Max Naimark who will remain a friend in New York. Alphonse and Gaston were famous at the time for being comedians and for practically falling over each other trying to complete the simplest task. Perhaps like a lot of high school students, there was discipline and rigor, but there was also laughter and fun as well. In the Collection's section of another issue of The Cardinal - Collections: Marcus Rothkowitz Common Name -" Marcus" Reason for Collection - His Debating Will Become - Pawn Broker The other students listed that they might go on to become an undertaker, a comedian, movie vamp, angry, a lunatic, slang inventor, a dreamer, lion tamer of the circus, a confidence man, tight rope walker, somebody's husband, and Bass for the Chicago Grand Opera Co. While the pawn broker does not sound very flattering, it does seem to be in good fun, and it is impossible to tell if Rothko suggested that profession for himself.

Gazing into the vast arena of life below him, Father Time lounges in his heavenly seat. There is something below that interests him, which seems to drive the age out of his morbid and wrinkled features and which seems to inject new strength and vigor to his shrunken frame. At first nothing is visible, but upon closer view the scene unfolds itself to be one of the comedies staged by the devil, the implacable enemy of the human race; Mars, the god of war and glory; and Mammon, the lord of the unholy coin and gold; which deities are now sitting Father Time's side, boisterously proclaiming their merriment with loud peals of thunder - to break the everlasting monotony of his vigil. But let us leave this scene for a location where we can procure a better and closer view which most of us have, no doubt, recognized as this world of ours with the act of life as a continuous performance. When you read this you just knew that the Seagram Comission was going to end badly forty years later. I was sitting next to Sue Friedman, who is Samuel Weinstein's granddaughter and Mark Rothko's niece, when we came across The Neighborhood newsletter at the Oregon Jewish Museum. I happened to be standing next to her when she read the first paragraph aloud, before adding: "You know, that Marcus was always so precocious," which I thought was funny. Like most students, high school was a complex experience for Mark. He already knew that the stakes in life were high, and it seems to me that Rothko saw his life in the context of a larger drama. In 1921, Mark graduated from Lincoln High School, leaving Portland to go to Yale University on a scholarship. Moving to New York After an unfulfilling experience at Yale, Rothko attended the Art Students League in New York for a few months, and then he returned to Portland in the first part of 1924, where he studied acting in a company run by Josephine Dillon. It is during this trip that he applies to become a U.S. citizen, a process that would not be complete until 1938. It is interesting that Rothko thought that it would be better to go to New York rather than Paris. At the time, New York was an art world backwater, the place to make it as a famous artist was Paris. The City of Light was the center of the art world of the 1920s with Matisse, Picasso, Giacometti and Duchamp either living in Paris or having major representation there. If Rothko wanted to go somewhere to be an artist, Paris and not New York would be the place to go. So why didn't Rothko go to Paris? First, in New York he had at least a support structure of family and friends, as slim as that support may have seemed at times. But Rothko was resilient, self reliant, ambitious, confident and able to persevere for long periods of time in difficult situations. Having family and friends in New York would have been helpful, but not enough for him to stay there. The other reason was that he may have intended to go to Paris all along, and New York would have been a stepping stone. Even by 1921, when Rothko graduated from high school, the First World War had been over for three years and a full seven years before he started taking classes at the Art Students League. Two things may have stopped him. First, Rothko had very little money, which made his family and friends all the more important. The second reason may have been that Rothko was not an American citizen, and perhaps he was concerned that if he left the country he would not have been allowed to return. Even as he returned to New York in 1924, Rothko's Portland connections continued to be of help. In 1927 Gordon Soule, a pianist from Portland also living in New York, put Rothko in touch with Louis Kaufman, also from southwest Portland. Kaufman told Rothko about classes with Milton Avery, an artist who would become very influential in Rothko's life. Rothko returned to Portland in 1933 for an exhibition at the Portland Art Museum. He and his young wife, Edith Sachar, had hitchhiked across the country at the height of the Great Depression. Before arriving in Portland, he stopped in Dufur, Oregon, where his brother Albert was living at the time. Dufur is twelve miles inland from the Dalles and is connected to Portland by either going over Mount Hood or going through the Columbia River Gorge. A few things had changed about Portland by the time he returned. Samuel Weinstein, his uncle who had built his family their first house in Portland, had passed away in 1925. Rothko's mom, Kate, now lived at 411 South Broadway. In Portland, Mark and Edith camped in a tent at Washington Park, where they drew the attention of the police for public nudity. It is good to see that some things about Portland have not changed.

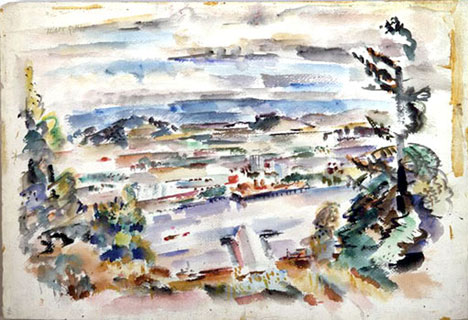

When he was not drawing attention of the police, Rothko spent time making hundreds of watercolors of the city and the spectacular views of the Oregon landscape afforded by the high elevation of Washington Park. I believe that the sense of place in those landscapes would never leave his work. They might be changed and transformed, but somehow their presence would remain. It makes perfect sense because those landscapes were the foundation of his skills as a painter and the beginning of his painting practice. Rothko would later give Portland a hard time for being provincial compared to New York, but I believe it was still a powerful source for him. Every time I look at Rothko's watercolors from the late 1920s, I get the feeling that he is looking at the space above the landscape rather than the landscape itself. It would be one thing if this happened in one or two paintings, but it literally happens in nearly all of the landscapes. I think that this is one of the critical differences between Rothko's early work and that of an artist he admired, Cezanne. When we look at a landscape in Cezanne's painting, we are looking at the landscape or at least the effect the landscape had on him. There is detail in Cezanne's landscapes that allows us to experience the rocks, trees and mountains in a much more intense and physical way than when we look at Rothko's early paintings. In Rothko's watercolors, the trees seem to be nothing much more than a vertical framing device, and the landscape (or city below) is useful only in conveying the feeling of the space above it. We are looking at the void, air, nothing. Here at some level he finds his language even though he won't realize it for nearly twenty more years.

Examples of his work at the museum are in black tempera and watercolor. There are twenty paintings by students, none more fifteen years old. From the Oregonian article: Mr. Rothkowitz intends to see how far, theoretically, freshness can be retained. His methods are simple. He says that he first impresses it upon the children that there are no technical difficulties in art, that good art is not a problem of exactness in reproducing what is seen, but rather a problem in beauty, of handling materials and subject matter so that the result explains the subject in a moving way and sufficiently for the purpose of the picture. On Rothko's own work in the exhibition: A hint of his admiration of Cezanne is in these water colors. They are carefully thought out and in no way theatrical or dramatic, as are the temperas which were spontaneously conceived and executed and which depend upon the richness of their blacks against white for effect. Those who admire the rich and velvety quality of the temperas will be mildly surprised that the artist combined only black watercolor or show card, the sheets from a 10-cent tablet of linen writing paper, with his own skill for desired effect. He must have liked the work that he made in Portland during his trip in 1933 because his first one-man show in New York at the Contemporary Arts Gallery included three watercolors made during his hitchhiking trip, including The Oregon Forest, Mount Hood and one called simply Portland.

There is always an unresolved tension between being an artist and being a provider for a family. In Rothko's case, Portland was associated with the needs and demands of the family, while New York was where he found his mature voice as an artist.

By growing up in Portland, Rothko forged bonds with other painters in New York who had also come from the Pacific Northwest. Clyfford Still spent many years in Spokane, Washington. Robert Motherwell was born in Aberdeen, Washington and spent time on the Washington coast up until at least the 1930s. Mark Tobey spent many years in Washington as well. I think that there is a shared background and a connection to the land between these artists that creates a strong bond. Yet Rothko needed to go to New York. Would Rothko's work mature in the same way if he stayed in Portland? Absolutely not. He need the interaction and the inspiration that only New York could provide. Strangely, I think Clyfford Still could have painted his mature work if he had stayed in Spokane. Would it have been appreciated or recognized? Probably not. Would Still have cared? No, that is why is he is great but that is the subject for another post.

While I wouldn't say that Mark Rothko's mature paintings stem from his experience in the landscape in Portland, the Columbia River Gorge and Mount Hood, I won't say that his mature work was entirely separate from those experiences either. His mature paintings are not landscapes but they are about a sense of place, a feeling that he first tried to articulate in the watercolors of the late 1920's. Looking at the space and color of the landscape in Oregon is fundamentally different than being in New York. Rothko reinforced those connections in the hundreds of watercolors that he would often do on his trips out there. Again and again, you see him painting not the landscapes but the space above the landscape. He is was always striving to convey the sense of place that he found in the landscape here. When we look at the watercolors, it seems like we are always staring not into the landscape but into the sky. The trees and the city grid below are not something that we feel a connection to but more as a frame for something that is harder to describe, space. This is an important difference between his work and that of Cezanne. In Cezanne's work, we feel like he is a rebuilding the landscape with each brush stroke in his painting. There is a real, physical connection between the painting and the landscape. In Rothko's early work, whether he realized it or not, we never feel that connection to the landscape. We feel the space of the landscape and a sense of place but these are different than rebuilding the landscape in the paintng. In Rothko's paintings, the experience is much more ephemeral and the trees that are painted seem to be framing space in the sky rather than bringing us back to earth. It is as though the landscape was useful in so far that it is leading us to a deeper, unspeakable experience. There is already something intangible that happens in these paintings even if it takes Rothko nearly 20 years to slowly work back to those experience in his mature painting. He might have been working back to something that at some level he already understood. The Portland landscapes did not need to be depicted in his later paintings, they were already in his fingers. Everything was right there at the beginning.

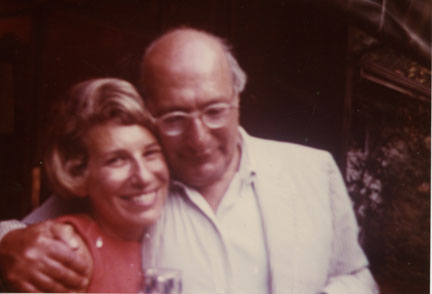

This project started one day with a conversation between Jennifer Yocom, Jeff Jahn and myself. There was the collective feeling that Portland had not done enough to recognize the time that Mark Rothko had spent in Portland and what implications, if any, it might have had on his mature work. It also raised the basic question: Could we still see Portland the way that Rothko saw it? James Breslin- Much to my chagrin I had spent many hours going through Portland directories thinking I had found something new only to discover that Breslin had found it years before. If any wants to learn more about Rothko's life, Breslin's book Mark Rothko: A Biography is an excellent resource. Bruce Guenther and Debra Royer opened the archives of the Portland Art Museum to me and were very helpful and supportive of this project. Judith Margles and Anne LeVant Prahl at the Oregon Jewish Museum were incredibly helpful and it was fun to go through some of their archives because they contain a unique perspective on Portland history. Scott Rook, Geoff Wexler, Sue Metzler at the Oregon Historical Society were incredibly helpful in finding neighborhood photos which gave me a very helpful perspective of what Southwest Portland was like during Rothko's timer here. David Anfam was very supportive and encouraging of my research and the premise of this project. The Portland Art Museum, Oregon Historical Society and the Oregon Jewish Museum.- We cannot know what Portland will be in the future if we do not know about the past. It is a simple as that. These institutions houses the cultural DNA of Portland. These institutions provide very useful resources for documenting and archiving and desperately need your support. All three institutions provide a unique and valuable record of what it is like to live in Portland. Dorothy Reiter is Morris (or Mish) Rothko's daughter and I had a very helpful telephone conversation with her one afternoon. Also the photograph of her and her uncle is one of my all time favorite photos of Rothko. Sue Friedman provided a Rothkowitz family tree and a critical moment. Thank you to everyone that helped me with the research on this project.

During my research, I found that doing research on business' and addresses in Southwest Portland from 1910-1920 was extremely difficult. Southwest Portland was very different. When I was doing research on Rothko's first house in Portland on 834 Front Street, I discovered that in the all of the street numbers were changed in the 1940's. Perhaps up until that point the streets were not numbered in accordance to the downtown grid and the city tried to connect them all together. This had the effect of changing the street numbers so 834 Front Street became 3434 Front Street. In the 1950's, Front Street was widened to become part of the 99W SW Naito Parkway/ Pacific Highway W. Other parts of the neighborhood were bulldozed to become part of the 5 freeway. 834 Front Street was bounded on the east and west by Curry and Whittaker. Front Street at the time was located between 1 st and Corbett. I think that Rothko's house in Portland is pretty close to 45° 29.886'N,122° 40.663'W which is a now in the middle of Naito Parkway and adjacent to a power station. Rothko wrote Doubon's Bride for the Neighborhood Newsletter in 1920 when he was 16 years old and a Junior at Lincoln High School. At least part of the story seems to be autobiographical. It is interesting to note that when his mother passed away, he supposedly stopped painting for two years and considered becoming a writer. Courtesy of the Oregon Jewish Museum.

Doubon's Bride By M. R. From The Neighborhood February 1920, pages 3, 4 and 7. A small band of refugees were wearily dragging themselves along one of the many roads to Paris- an every day scene in France during the World War. The inhabitants of the small towns surrounding the capital were abandoning their homes in the face of the German advance and fleeing for Paris. The sun had already sunken behind the low western hills; evening was coming on. The refugees, aware of this, left the road to find to find a camping place for the night. When they reached a small, wooden section, they lowered their packs which constituted their earthly possessions, spread out their blankets and divided what little food they had. As they sat under the trees, eagerly partaking of their meager course, they made a very impressive picture. Their faces were drawn and haggard; their eyes glittered brightly from constantly endured hunger. A shadow of fear caused by the horrors experienced and the perils lived thru the past two years were heavily traced upon their countenances. Their clothes were torn and ragged; the shoes of those who had any good fortune to possess any were torn to pieces and many were bare footed. They were all very, very weary. One of the refugees was a tall, handsome, young man, who appeared to be not more than 16 years old. A beautiful child of four years of age lay sleeping at his side upon a torn coat, having fallen asleep through sheer exhaustion, crying: " Where is Mama? Where is sister Marie?" The same questions was in the mind of the older boy. As he sat beside the sleeping child, he reflected on the recent events. Before the war, the two boys, their sister, father and mother made a happy family in Valney, a small village, just south of Chalons, fifty miles from Paris. The father provided quite a comfortable living for the family, working in the family drug store. Two years earlier, when war was declared, the father went to defend the flag of France. Six months later notice was received that he died gloriously on the battlefield. The little family bore the loss bravely. The boy secured work at a neighboring farm and his sister sewed for the neighbors. But only two days ago, at daybreak, while the entire village was peacefully slumbering, a detachment of French soldiers stationed in the village received orders that the village should be evacuated immediately, as the Germans would attack in the morning. They ran from house to house awakening the unsuspecting inhabitants and breaking the terrible news to them. At once the quiet village became all bustle and confusion. The inhabitants were rushed toward the trucks which were sent to carry them away. Our little family was among them. The mother held her youngest by the hand, but in the great excitement, she unconsciously let go of it. When their turn came to climb up in a truck, it was discovered that the child had disappeared. Jean, the oldest boy, was sent to find the child while she held their places on the truck. Jean wander throughout the entire village, but the child was not to be found. Finally, he decided to return home and search for him. Sure enough, as he approached the cottage he saw the youngster devoting his entire strength to the task of pulling a toy horse down the steps. "Ah, you bad boy! Where have you been?" he cried at the same time embracing him. "I forgot my horsey. I came back to get him," replied the boy laughing. Picking up the little rascal who was kicking and screaming with all his might, Jean ran with a happy heart toward the place where he had left his mother and his sister. But when he reached the place, his eyes filled with tears. The trucks were no longer there; neither were his mother and sister. He spied a soldier to whom he ran and told his troubles. "My god boy! That must have been the woman and girl who were screaming that their boys were gone! We held back a truck for them for fifteen minutes, then we shoved them in and sent them away. We thought they had become hysterical from fright. You better get away as quickly as possible for the Germans are very near." With these words he left Jean and his little brother and in a few minutes returned with a bag containing black bread and a keg of water. As Jean turned around he saw the soldiers making sand bag entrenchments. The noise of the bombarding was now very near. He took his brother in his arms and started for the road. After walking four hours, he reached it. As he turned to get a farewell glimpse of what had so long been his home, he realized that he would never see it again. Just then, a great volume of smoke was arising from the place where they village had been. The large city with its beautiful tall parks and wonderful works of art fascinated Jean. However, he could not give much thought to the exploring of these wonders, knowing that he must provide a living for himself and his brother and must find his mother and sister, but he could obtain no work. The city was flooded with refugees so that the opportunity of securing employment was lacking. The city was flooded with refugees so that the opportunity of securing employment was lacking. Moreover, Jean was not a very business like fellow who knew exactly what he wanted; neither was he trained in any special line of work. So he kept up a bare existence by doing odd jobs, and many a day passed when both boys hungered. Meanwhile, he searched for his lost mother and sister. Daily, he inquired at the police station, railways stations and at every other place where people were apt to congregate. But he always met with disappointment so that he gradually lost hope of ever recovering his family. Once, two days passed with his earning anything. On the third day, Jean left the poor hole which served as his home to try his luck once more getting some work. All day he searched without results, but on his way home that evening, as he sat down on a curb to rest his aching feet, he noticed a small wallet lying in the gutter. He picked it up and upon opening it , to his great joy he found a few francs and a folded paper. He rushed to the grocery store, bought milk and rolls and hurried home to his hungry brother. At home, he examined the wallet more closely. Spreading out the folded paper, he saw a small drawing of which he could neither make head nor tail. He also found a card inside bearing the name: Charles Doubon, 176 Rue de Rueler He decided to return the wallet on the morrow. The next morning Jean knocked at the door of a small, beautiful home in one of the exclusive districts of Paris. Charles Doubon, a handsome man of about twenty-five years of age opened the door himself. There was never a man more joyous than Doubon upon regaining his possession of the wallet. He could not find words with which to thank Jean. He held a position, he told Jean in the Bureau of Munitions. The scroll of paper was a plan for a new projectile he had invented, which he was to present to the War Ministry the following day. He offered Jean a large reward which was refused. However, he was not allowed to leave until he promised to call again. Jean kept his promise, and in the next two weeks became an intimate friend of Doubon and his aged mother. He brought his little brother frequently and the young chap won their admiration. He was given a position in one of the munition factories that Doubon controlled. At first, Jean hesitated to tell his story to his newly acquired friend, but as the ties of the friendship between them were strengthened he determined to do so upon his next visit. Upon that occasion, Doubon drew him aside and said "Jean, I am engaged to a wonderful girl. She came to my office six months ago, and I loved her from the first. I must call on her now. I'll take you home, but remember , be here tomorrow evening to meet her." Jean congratulated his friend heartily and started for home happy because of his friend's happiness. On the next evening Jean arrived at the Doubon home at the appointed time. He kept up a conversation with Madame Doubon for the others had not yet arrived. Soon footsteps were audible on the verandah. The door opened and Charles and his fiancé entered. "Hello, Jean, here we are! Meet my bride. I have been telling her about you," broke in Doubon's cheerful voice. Jean hastily turned around and looked at the girl. For a moment they stood staring at each other; the next moment they were locked in each other's arms, crying:

Doubon was bewildered. But after Jean and Marie became calm the explanation was given. Marie was Jean's lost sister. "Where is Mama?" cried Jean. "And where is Baby?" broke in Marie. Doubon volunteered to get the other members of the family, but Jean and Marie were too anxious to meet their lost ones, so left the house with Doubon to greet their mother and brother. On the way, Marie told Jean how they were thrown into the last of the trucks, of their attack by the German cavalry, of their escape and how instead of being taken to Paris they found themselves in Chalon, where they secured work for a few months and accumulated enough money to get to Paris. Mid tears and laughter, Jean and the baby were soon folded in their mother's arms and in the recital of the adventures , the time of their separation and sorrow were forgotten in the happiness of the reunion. Posted by Arcy Douglass on June 17, 2009 at 9:13 | Comments (3) Comments Arcy, Thanks for the time you spent researching and writing this article. Posted by: LaValle Thanks for bringing that up, PORT did a post on that Rothko painting, it wasn't in a private collection, it was on loan from So, if you have about 150K to burn, give Bruce a call at the museum... ..somewhat half seriously, Arcy and I have discussed how long a lemonade stand at the site of one of Rothko's local haunts would take to raise 150K. Oy! Posted by: Double J I loved this! Thanks so much for the history. While I've long loved Rothko, I had no idea about his Portland history. BTW, the Twitter sign in for comments doesn't work, after accepting the twitter app it rejects after the 'share email' and blocks comments. Posted by: Carissa Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)