|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

The Primacy of the Mark: the Brice Marden Retrospective at SFMoMA

Brice Marden has been trying to bring the experiential quality of making and looking at paintings into the foreground of his studio practice for forty years. If there has been a common subject matter to his paintings, it would be about the long, slow, patient observations that the paintings require and the effect those observations have on the way we see ourselves and the world around us. His career has been an exploration of the ways that different forms and surface could be used to tighten the image to the picture plane. He has, on his own terms, been always trying to cut through to what is the essential nature of painting, and he does it by asking a series of questions: when does one color change to become another, when does one object transform into another, and what effects do the paintings have on the people that look at them? So it was no surprise to be confronted at his retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and to feel like you were walking through a series of paintings suitable for contemplation by Zen monks. The retrospective which started at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, travelled to San Francisco and is now continuing on to Berlin. Like all great painters, Marden's paintings tell us more about ourselves than we ever thought was possible. Marden's work has always been about transformation of colors, planes and lines into something transcendent. Guided by a rigorous process , he has consistently found ways to allow his painting to take on a life of their own. The early monochromes were all about how can one color can be overlaid with another to create a third new color. The Cold Mountain paintings are all about how one line can be overlaid with a series of new lines to become something else. So his painting is always about a series of a little steps that when taken together achieve something quite extraordinary. His work is a constant dialog with the materials: the weave of the canvas, the viscosity of the paint, and the length of the paint. All leave an indelible mark on the paintings. The paintings are about his process in the same way that Pollock's drip paintings are about the movement of his body and the buckets of paint. Everything is completely legible and every mark counts, even if is erased or painted out later. Marden's paintings are slow. Slow to make, slow to evolve and slow to take in.

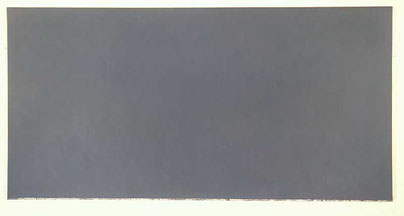

I was surprised about the stillness that was created by this first group of paintings. Since there is nothing to the paintings except for surface and color, the paintings become about what you bring to them. Who are you at the moment, and how is that reflected back to you at the moment through the soft dull surface of the painting? It was the stillness of these paintings that created the atmosphere of contemplation. They were completely open and completely closed at the same moment like Zen koan. I was a little shocked at how little of the stillness of these paintings has carried over to contemporary painting; we just do not see anything like this today. Maybe we do not have any need to be still or quiet anymore, or perhaps these qualities do not make the paintings exciting enough.

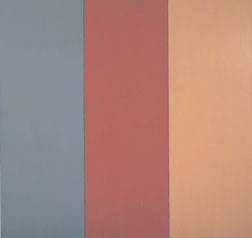

Perhaps it was not enough for Marden as well since the stasis of the first gallery is dissipated as you walked from through the next series of galleries, where the paintings are made of multiple colored panels juxtaposed one right next to each other so that each painting is an accumulation of monochromes. The panels become more about the evaluation of what each painting is through the linking of the colors of the painting from one panel to the next. Although the paintings are beautiful, you cannot sink into them like the simpler monochromes that started the show. The splits in the panels also remind you of Barnett Newman paintings, except that in this case the zip is actually three-dimensional because it marks the joints between two panels. The early monochromes were about the totality of the painting, while the later paintings are about evaluating the relationship between each of colored panels. In a strange way, the simplicity of the earlier paintings allowed them to be more inclusive, more holistic, so that they could be experienced in their totality without judgment. The later paintings become about aesthetics and evaluation between the panels, and therefore tend to be about something else. One exception to this is the painting Adriatic, with a dark grayish green over a dark bluish gray, reminds you of the calmness and tranquility of being on a ship and looking out over the Atlantic on a moonless night.

Another exception was the painting that also ends the first half of the show, the immeasurable The Seasons owned by the Menil Collection in Houston. It is nice that these beautiful paintings ended up in Houston, where they are only footsteps away from the Rothko Chapel. These grand paintings are amazing because they are about Marden's ability to capture in a single complex layered color the essence of a season. Here the panels are not attached and the gap provides much needed breathing space that allows each painting to be viewed on its own. In this case, the gap allows you to swim in the space and color of each season before you move on to the next panel. While the painting looked beautiful and was very well installed in San Francisco, I got the feeling that it probably is even more beautiful in Houston, where is could be looked at in relation to the outdoors and perhaps by literally watching how you and the painting might change over the course of a year.

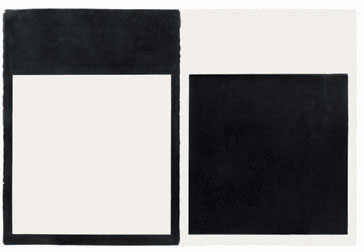

The galleries of paintings are interspersed with smaller, darker rooms in which his drawings are sequestered together. I understand that for conservation purposes the drawings might be light-sensitive and by keeping them together it gives more breathing space for the paintings, but I think it sets up a false distinction between the paintings and drawings. Especially in the case of Marden's work, his drawings express the same ideas of the paintings with the same rigor, but with different materials and on a different scale. I was impressed with the way that he is always very aware of the surface that he is working on and how that can modified to suit his purposes. For example, when he was working on the monochrome paintings, he was also working on drawings of pencil, charcoal and wax in which the image doesn't sit on the surface of the paper but is slowly and patiently worked into the paper. The technique might be scraping away a thin layer of paper with a razor blade to allow the image to be flush with the paper or smoothing the worn paper coming apart from being worked with a tip of pencil with a thin layer of wax. These were some of the most complete drawings I had ever seen with all of the power of the paintings, just in a different medium. They are worked and reworked with the same intensity and focus as his paintings. The dull reflective quality of the wax also give the surfaces a slight give so that you sink into the space in the same way that you could with larger monochrome paintings. In the late seventies Marden must have begun to feel trapped. Maybe the paintings had become too fussy because they were about linking these panels of colors, and it was getting harder to go deeper. He was no longer able to say what he wanted and he needed to evolve his language. I think during this time Marden began an intense dialog with Richard Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series, both the paintings and the drawings. I think that Marden was looking for ways to push more space into the paintings by dividing the rectangle with a series of vertical, horizontal and the occasional diagonal lines, which is exactly what Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series is about. It also worth noting that in his drawing, Diebenkorn began using white gouache or paint, to cancel out lines that did not work, which in turn created a sort of counter image of erasures. Diebenkorn might have been looking at Matisse (see his View of Notre Dame from 1914 ) when he came up with this, but that is for a different review. This is an effect that Marden uses in a new way and very successfully in his drawings related to the Cold Mountain paintings.

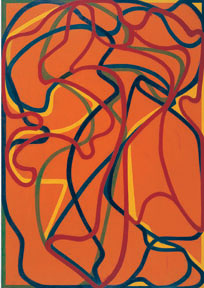

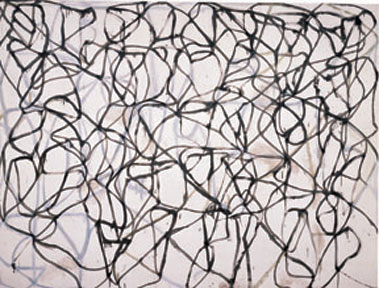

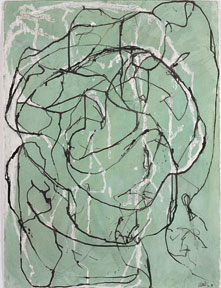

In the mid-eighties, Marden reinvented himself by moving away from his signature monochrome paintings and in a direction that created paintings that have more space and were inspired by Japanese calligraphy. I think in some way both too much and too little is made with Marden's interest in calligraphy. The retrospective really made it clear to me that during this time Marden's painting process evolved but didn't drastically change, although the paintings look very different. He moved away from the wax, switched to Terpineol, and the large planes of color become lines that were worked over in more or less the same way as the earlier paintings. The method, approach, focus and the layering of different colors were still the same, although they were used to different ends. They never stop being Brice Marden paintings. Marden's interest in calligraphy culminates in the early nineties with the Cold Mountain paintings based on a series of poems by the Chinese hermit Han Shan. These have always been some of my favorite paintings because the overlaying of the lines allows the painting to grow and evolve in a unique way. Also, some of the spaces and shapes that are created by the lines are really beautiful and extraordinary. You can see everything in these paintings. From the marks of the palette knife, to the dripping paint, to the lines of paint being sanded down to expose the weave of the canvas. Like in a Pollock painting, no single line is more important than any other one, but it is how they work together to create the totality of the experience of the painting. For me this directly relates to how Marden used to paint the monochromes by painting layers upon layers of color to create a new unexpected color that was the essential quality of a particular painting. In each case, the process is used to go somewhere you could not have predicted in advance which is suitable for a series of paintings based on the writings of a Taoist hermit. If in the earlier painting the brush strokes are scraped and encased in wax, in these paintings the marks are left to stand where they were placed, being metaphorically open to the sky and to the natural weathering of being outside. These paintings are all about nature, being in the mountains, the firmness of stone and the fluidity of water, while breathing the cool clean mountain air. Before the show I had always thought that my favorite Cold Mountain painting was Number Two, which is owned by the Hirshhorn in Washington D.C. But walking through the retrospective I think that Number Six (Bridge), owned by SFMoMA is even better. In Bridge, those lines are intertwining with such complexity there is a real transformation from the five couplets of calligraphy that formed the base of the painting. In reproduction it hard to understand the scale of the painting, but when you are standing in front of it, it is very large. The paintings are about 9'x 12', which means a lot of the lines are about two feet long. It is amazing that a painting made up of so many smaller line segments can be put together to form such a strong coherent image. Like all of Marden's best work, the painting slows you down. There is a lot of information to take in and you have to take time to absorb it. Like most great paintings, they reward a prolonged viewing, and we are transported outside to the mountains of China to spend time with a Taoist hermit from seven hundred years ago.

Some of the lines are painted out with white paint. This pushes the erased line back in the space of the painting and forms a coherent counter image of erasures similar to Diebenkorn's Ocean Park series. Other painted lines are sanded away to reveal the grain of the canvas so it mutes the color of the line like a halftone. This is a little surprising because it is something that is quite common in traditional Chinese landscape paintings as well as the paintings of someone like Titian or Rubens, who consciously use the grain of the canvas to supplement and alter the colors of the paint. I think this touches on one of the great things about these paintings in that they are taking the best of both eastern and western approaches to paintings. Marden is always is looking for new ways to exploit the potential of all the materials that he is working with. When you are looking at the paintings, you feel like you are in the middle of three-way conversation between the artist, the materials and his influences.

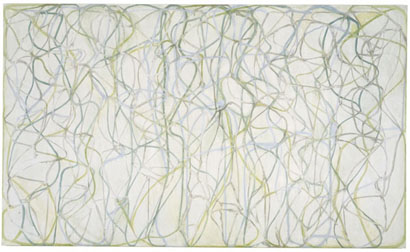

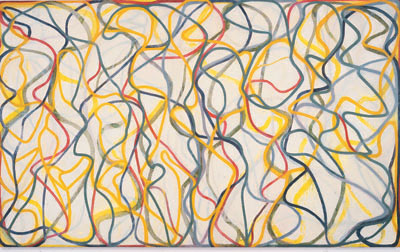

At the end of the long gallery with the Cold Mountain paintings is The Muses, which is one of the most beautiful paintings in the show. The Muses were painted right after the Cold Mountain paintings and is the grand finale of the Cold Mountain period. The background is much greener and the lines are much more silvery than the other paintings. The Muses is owned by the Daros Collection and again was one of the paintings I would love to see at its permanent home. In this case the Daros Collection is in Switzerland, so I can only imagine how the greens, grays, and blacks would play against a backdrop of the mountains there. After the Cold Mountain paintings, Marden's language began looking for new ways to capitalize on things he saw and learned from these paintings. The development of Marden's language has always followed his exploration of finding new and different ways of tightening the image to the picture plane. The monochrome paintings were about holding the picture plane, not only with a color but with a surface that was a counter intuitive because it was waxy and soft. Later when he began to look at Asian art, he was interested in holding the plane with overlapping lines. Since the mid-nineties he has been trying to hold the pictures plane with lines that are connected to form a coherent shape. These shapes are given individual colors so that when you look at his more recent painting you can clearly read the shapes and how they stack one on top of the other. The effects of looking at the newer paintings are sometimes not that different from looking at images in flip book where a single image is multiplied to create an animated vision of a space or object.

Although there have been some brilliant paintings with this new way of defining space, such as Marden's Study for the Muses (Hydra Version) and Bear Print, I have often found these new paintings more difficult to get into. When you are looking at one of the monochrome paintings, you are drawn in to the space of the painting because every mark and every subtle shift in color become significant. Later in the Cold Mountain paintings, the layers and layers of lines accumulate to form spaces and shapes we could have never imagined and could not be created any other way. In both cases, the method extends the language of the painting to reach a new or unexpected territory, and like in Pollock's painting we are along for the ride. In the newer paintings the process is a little too straightforward without enough breathing room to allow the method of the painting to transform into something unexpected.

Study for the Muses (Hydra Version) works because the shapes reach a sort of critical density where it is impossible to follow any single shape for very long and therefore we have to open ourselves to the totality of the painting as whole. It is a beautiful painting, but you can see that it was either hard to sustain that density in the other paintings or Marden made a decision in which he wanted to have the painting be more open and legible. Perhaps he thought that he could hold the picture plane with just two or three shapes, which you might be able to if they were all the same color, but if they are different colors it is impossible to generate a critical mass. An example of a painting in which I feel these relationships break down and that there is not enough energy to hold the picture plane would be a painting like Epitaph Painting 5. Even in Pollock's painting, he never tried to hold the space with a single stroke or form, but he unleashed a whole array of different brush strokes to generate the density required grab hold of the picture plane of a large painting. Pollock was never seduced by any one gesture, and up until the more recent paintings, neither was Marden, and that was the genius of the work.

In a way Bear Print is the exception that proves the rule. The lines in Bear Print were actually transferred from another painting that was beginning to break down. The transferring of the lines, by "printing" it canvas to canvas, reversed the image, and provided much-needed distance between the artist and the painting. After the image was transferred, the painting was completely reworked, but it is critical that transfer resulted in starting point that Marden could not have anticipated when he started the original painting. Bear Print is successful because the separation between the intent and effect that had happened in the transfer and reversal was enough to open the painting so that it could transform into something else. So in this case the lines and shapes were enough to hold the space of the canvas but the caveat was that they had to be put on in such a way that it allows the work to get outside of the artist. I am not just being critical of Marden here, but these ideas are all the backbone of twentieth-century art, namely different strategies of separating the artist from the painting in order to get the painting to take on a life of its own. If it could have been done a different way, Pollock would not have had to drip paint, Newman would not have had to reduce his language to zips, and De Kooning would not have had to paint his paintings over and over again, just to name a few artists. These are all ways of separating the artist from the work so that the work can grow on its own unimpeded. There is no shortcut and it seems like at one point Marden understood this better than anybody but maybe he has forgotten.

It was a little strange at the end of the exhibition to come across a room full of two sets of the painting The Garden of the Propitious Image, the first and third versions, which are Marden's most recent works. They formed a strange bookend to the monochrome paintings that started the exhibition. The monochromes, which might at first glance give you nothing, end up giving you everything by making you aware of yourself. There is plenty of room to breathe and the move around. In the Garden of the Propitious Image, the background and the shapes cycle through six colors of the spectrum in so that the order of the colors changes from one panel of the painting to the next. In these paintings, there is no more room to move and no room to breathe, because the panels are so close to one another and that each a panel has to have six layers (the background plus five shapes) so that the system will work. The work never transforms and the panels are never allowed to evolve because that is not what the system is about, or perhaps the changes between the panels became too forced and lost its opportunity for natural growth. In this case, I think that Marden followed his system, which has helped him so much in the past, too closely because it extinguished the life of the paintings. The colors are beautiful and the craft of the paintings are amazing, but there is no room for us to get into the painting and that is what makes them slightly decorative. In Brenda Richardson's great catalog essay, Marden mentions that he could not wait to start using the colors black and white again, colors which are not included in the Garden paintings. I was a little shocked at that statement because I could never imagine an artist like Pollock or Cy Twombly saying something like that because it would have meant that the painting was not changing with them and that the painting was somehow separate from where they were at that moment. If Marden was getting a little bored making these paintings, where does that leave us?

Marden is constantly evolving his painting language to suit his needs. He is always growing. When you are looking at his paintings you get the feeling that he questions everything: his materials, the supports, the image, the plane and his purpose for making a painting. On the plus side, that gives his work a rigor allowing it to open up in whole new directions. He is also an extremely successful artist so that he can have studios all over the world, but it really does not mean much if he loses his connection to his work. Marden also brings out the idealist in me because I have always thought of him as having some of the most romantic ideas about art and being artist. As one of the most famous artists in the world he deserves to be held to the standards by which all great art is judged: how does a work a change the people that take the time to experience it? It is on these grounds that I think his more recent paintings are less successful, but perhaps they have just been stepping stones to a broader breakthrough. Marden has always found ways to reinvent his painting to make it more relevant to himself. He has never allowed himself to repeat the same ideas over and over like other successful artists. He has always pushed the boundaries of himself and his medium to make it more relevant to his current interests and to the way he sees the world. Nobody who pushes that hard can always make perfect paintings, but the key is to keep changing and evolving. But when I was walking through the retrospective, it was like some of his earliest work is more relevant to the interaction between the artists, the paintings and the audience than his later work, when really it should be the other way around. All of the artists that Marden admires either died young or got better as they got older. We still need great painters, perhaps now more than ever, and we want to be challenged in the way that great paintings have always made us feel more alive and connected to world around us. Posted by Arcy Douglass on May 30, 2007 at 9:48 | Comments (15) Comments I'll always love Marden's monochromes and I like the Cold Mountain series as a more rehearsed all-over Pollock moment... but is he too rehearsed like Sean Scully is? Refinement for refinement's sake frankly pisses me off. Its an uncertain world and I want uncertain art... not the Hampton`esque version of "diversely hedged risk," in paint form. I'll take Karin Davies over Marden's later stuff. Ellsworth Kelly seems to have kept his edge... Marden seems comfier, but that's just me. He's still real good and a lot better than Sean Scully. Posted by: Double J I think that I understand what you mean about the work appearing too rehearsed because in the case of Marden's work, he is as he likes to say working within "Spartan Limitations." He is always working within a set of closely related ideas that he has developed over the decades of his studio practice. I think your analogy with Scully is a good one because I have always thought that Scully's work is not about formal invention, he would be the first to tell you that he did not invent painting with vertical lines. I think that he would say that his art is in the way that those lines are painted and the way that those marks can convey an emotion. I wonder if Scully would say that by freeing himself from formal invention he could get closer to what he thinks is important in painting: the emotional connection. The paintings become about different ways of tapping into the way that a variety of emotional connections could be expressed. I think Scully is more interested in what Chuck Close calls an "invention of means", meaning how is a work actually made and how can that be used to convey an idea. Prompted by your response, I think that Marden's monochrome raise a seies of interesting questions: where is the art? is it in the viewer? in the painting? in the materials? in the connection between the two? I think everyone has to answer this question for themselves and it is probably what makes art so exciting and dynamic because it is always being redefined. I think that Kelly is much more of a formal painter than Marden or Scully whose work functions on a different level. I am speculating but maybe Kelly's work is about the way a piece relates to the space of the room while Marden's and Scully's work is about the space within the frame. That is sort of interesting because the might seem to be similar but I think that the view relates to them in completely different ways. In all three cases I think that each artist does their best to paint themselves out of the picture. So I do not think it is necessarily refinement for refinement's sake, I mean you go where the work takes you. Some steps in the development of the work are just larger than others. I think that each artist would stop if they weren't saying anything new. Posted by: Arcy I’m a new visitor to Port, but after reading comments posted to Arcy’s article on Marden comparing the work of Marden, Sean Scully and Karin Davie, I had to respond. Let me quote Marden at the outset: “And I paint for anybody that’s willing to look at it. Really, at heart, for anybody who wants to see it. And when I say see it, I mean see it. I don’t just mean look at it.” I think the distinction between looking and seeing is a good one. How much “there” is there? Does the work reward sustained attention? If it is another “one-liner”, maybe a magazine or book illustration of the work will suffice. But if there is more going on, if the artist is truly and deeply engaged, aren’t I obligated to give time to “seeing”, and seeing the actual work before I offer a critique? I saw the Marden show in NYC at Moma last December. I’d read the literature, of course, and seen many individual works, but I wanted the long view. And to give the retrospective time to work on me, I “saw it” over two successive afternoons. Re. Arcy’s comments on Epitath Painting 5 and The Propitious Garden series, I think Marden is doing something more than “holding the picture plane” here. I too love the monochromes but this is different territory. The colored lines each sing from different depths within a picture. It takes a while to “see” or hear their chorus. Sometimes harmonic, sometimes contrapuntal, these voices sing fugues. And for an artist to create fugues takes “rehearsal” time. Years of practice. Why does Itzhak Perlman move us? “Refinement” is what nets the spectator the continual surprises and resonance from “seeing” the work. And this uncertainty is of a different order and more sustainable than any superficial novelty. Karin Davie? I was in Sotheby’s two weeks ago and looked at her two diptychs there, part of the Contemporary day sale on 5/16. A look was enough. Emotional Depth? I know Neo Op is fashionable, but beneath the calculatedly energetic surface play, there was not a lot to “see”. Uncertain art”? More “hedged risk” I think. After seeing Marden at MOMA last December, then hip-hopping through Chelsea, I went to the Met. Posted by: artworker Well, I do like Marden so take my comments as relative. First off, Rothko has no heir, except maybe Judd, who also has no heir. Also, refinement isnt bad thing but what one trades or doesnt sacrifice to achieve it says a lot about that artist. As for Marden, It gets down to taste so there is no right answer. Ive seen a lot of his work over the years and the issue for me is.. does Marden paint a lot of pretty good paintings at the expense of painting few if any great paintings? This is my issue with risk and Marden (and I consider him second tier to Ellsworth Kelly). I see Marden just fine, even love many of them but he's definitely a painter who hits a lot of high percentage. Davie is a different kind of artist. True Davie is a lot more erratic, she's got lots of stinkers but when you compare her "Pushed Pulled Depleted and Repeated" to anything Marden has done there is a sense he's part of the painter's discussion that she out flanked. Nothing wrong with either strategy. Sean Scully is fine too but I think it is Mardsen and Scully's epicurian quality that both makes them good... but not first tier. The question with Davie is more, can you top what you did back in 1999 without repeating yourself like Marden or Kelly seem to do? Her painting titles already give the answer. Maybe Marden and Davie are not the right artists to compare... how about Marden and late de Kooning? Somehow I sense de Kooning forgot more than Marden had ever learned. Marden is a really good painter, a really great painter though???? Posted by: Double J I think the comparison between late De Kooning and Marden's work is worth exploring. While Pollock's process was essentially additive (with a few exceptions including Out of the Web), meaning that he resolved a painting by adding more and more layers of paint, De Kooning process goes beyond elementary mathematics and probably gets into the artistic equivalent of calculus. De Kooning talks about how he deliberately tries to put himself into place where he doesn't know where a painting is going and he is not on stable ground. He is trying to paint outside of himself or you can look at as he is trying to paint himself out of the picture. There is a story of De Kooning when he was a teacher at Black Mountain, North Carolina. Albers' hired him because he was an avant-garde New York painter and that's what the students thought they were getting. Anyway, De Kooning walks into class and puts down a vase of flowers. He says that they are going to keep painting the same vase of flowers until naturally goes away or turns into something, and then they were going to keep painting it until the flowers naturally came back in there paintings. Half of the students walk out because in their mind this is not what modern art was about and the other half stay and do their own thing over the course of the class. Only De Kooning keeps working on the same thing and it turns into Asheville(?). First the discipline to keep working on the same thing and keep painting it over and over. Second, he set up a process in which he did not know what was happening next and that over time he could bring together all of these forms in new combinations. It is a very non linear, quasi- random in the sense that you can take advantage of an accidents along the way, very intuitive painting practice. Third, the painting is not about a single move, form, or color but it is about an accumulation of steps and processes in way that De Kooning could not predict in adavance. All of this comes to ahead in 1977, when De Kooning stops drinking and gets on a roll. Besides being Dutch, you could take one of these canvases and put it in the Rembrandt show and it would fit right in where as I am not sure that a Pollock or Marden would. There language is different where sometimes a De Kooning is like a blown up detail of a Rembrandt with more colors. De Kooning and Pollock (also Rothko, Newman, Still, etc.) reinvent painting in the late forties and early fifties and so where does that leave the rest of us? I think this Marden's dilemma. After all of the formal invention of the fifties how do you begin to make a painting that makes sense to you. First, maybe there is not much formal invention left to be developed so you are left with working variations on the processes of these other painters to see if you can get somewhere else. In Marden's case, I think that his process is closer to the additive process of Pollock but just slowed down. Each mark is felt and thought about in way that was intuitive and fast for Pollock. Even when Marden erases, you can still see the mark, and he doesn't necessarily put something completely different in its place like De Kooning would have done. But that said, I do think that Marden is a great painter. Not only the Cold Mountain paintings, The Muses, and the Hydra Version of the Study of the Muses are all first rate. But he his just different than De Kooning. I think one of the big differences is that even though Marden's work is about layers, De Kooning's and Pollock's work is about layering different kinds of marks, textures, and Pollock's case objects. I was in Seattle this weekend and I was looking at Pollock's Sea Change at the Seattle Art Museum. I think the varnish that they put on it was too glossy the painting itself is beautiful. You can really feel the tension between the brush strokes of all of these different colors on the under layer of the painting and the pored black enamel over the top. Pollock was even looking for more texture so he put little stones and pebbles to transform it again and amazingly it works. The result is a really complicated painting where you have all of these graphic languages and systems interacting and overlapping each other on the plane of the canvas. The painting is also not beautiful in the way that Marden's paintings are, but still there is just so much there. I wonder if Marden and Scully, like a lot of other painters today, have fallen in love with the image, which is not necessarily representational image but could be any preconceived idea, while Pollock and De Kooning did everything they could to destroy it. Posted by: Arcy Double J seems to see art activity in combat terms, with artists risking and strategizing, outflanking and outranking other artists. This plays right into the old fashioned notion of the avant-garde. Ah - the illusion of progress. Competition, novelty, fashion: Better bumpers, lower profile, we have it in wasabi green this year! From the composer Bela Bartok: "Competition is for horses, not artists". Rothko knew that. And so does Scully. Art for both of these artists was/is a meditative activity, focused on the numenal world instead of marking territory or scoring points. ",,,epicurean qualities"? "Taste?" Boy that's another one. With maybe a little whiff of class consciousness, social darwinism? "top tier"? Better Kuspit's "good enough artist" (see "Signs of Psyche in Modern and Postmodern Art"). Better to see the artst's role and art activity as "self healing" and "world healing" finding a balance betwen inner and outer worlds, making both better paces to live in. Read Dore Ashton's book: "About Rothko" or Bonnie Clearwater's new "The Rothko Book". Rothko wasn't interested in "form" or "color" - he was always adamant about that. He was interested in emotions and light (as insight, illumination). Epihanies then. Not simply epicurean delights. It's not dullness or lack of courage (to "risk") that has artists working in series ("repeating themselves") - but the possibility of...revelation. I see Scully and Rothko as illuminati, revelators, healers. And Judd? Not Rotko's heir surely, but rather a constructor of high end decor. Years ago, drinking with Phillip Guston into the early morning hours. I'm paraphrasing, but this is close: "Art is not a matter of self expression but rather self expansion". "I'm lucky if when I'm working, Rembrandt and Piero and all the rest, who have been looking over my shoulder, I'm lucky when they leave the room. Then, it's my contemporaries who argue with me, observe me. If I'm lucky, they go too. And I'm left with myself. But I only really make art - when I leave the room". Posted by: artworker Arcy and artworker- Finally some folks willing to talk painting - and to a refreshing depth that we don't see here in Portland much. artworker - if you really drank into the early morning hours with Guston, I am truly truly insanely envious. Posted by: graves Graves. My night with Guston was in 1967. I just finished my MFA. Our converstaion took place in his kitchen in Woodtsick over innumberable Budweisers. I recall him complaining about Warhol spoiling his appreciation of the beer label. All Guston's generation had problems with Warhol.. No wonder. Rothko had called his paint, the media which registered that wonderful touch of his, his soup. Warhol, denigrating the notion of touch and spirituality, had his employees silkscreen images of EMPTY SOUP cans onto canvas in his FACTORY. Those paintings were a direct slap at Rothko. Posted by: artworker This is a first, I am actually coming to the defense of Warhol. I read that somebody said that Warhol did the best portraits of the 20th century. They are slick, high contrast, on colorful back grounds that sort of represent the shallowness of the high speed modern life that we all lead. He was an artist of his times and unfortunately his times are still our times. He does not go away. Elvis, Jackie, Marilyn all pass away but his images keep bringing them front and center. There is also the whole obsession with celebrity which is the dark side of the American Dream. If you can live it yourself, you surround yourself with images of those people who do. For better or worse, Warhol captures this perfectly in the shallow alienation in his paintings. To paraphrase our Lou Reed song "He is our mirror". Last thing, and then no more Warhol from me. How many collectors owned Rothkos and Warhols? I do not know but probably alot. They are like two sides of the same coin, very Tao... Rothko's painting's are beautiful but like all good ideas they need to be reinvented and reworked by a younger generation for a younger generation. I mean you do not get Carravagio without the example of Rubens/ Velasquez. I mean Rothko's paintings are gorgeous but if they are locked up in rich people's houses and in museums they lose currency in contemporary culture. They inevitably become someone else's, as the sky high auction prices demonstrate, and not our own. If ideas in art, or anything else, are to continue to be relevant they have to been owned and experienced by those who are living at that time. Book knowledge (read museum visits) are one thing, hands on practical experience is something else. Scully is interesting because he shows us a way that Rothko's ideas can be carried forward just as Marden's work is a critique and affirmation of Pollock. I don't think that one is better than the other because both parts of the process are necessary. Warhol shows us our dark side even if we don't like to see it. This is why making art is so difficult because to be influenced by Rothko you just can't copy Rothko you have to find your own way. You have to take his language and make it your own. Picasso did this with everybody. Rothko did this with Matisse. You are just adding more information to the discussion. But it works both ways, by looking at Rothko maybe we can understand Matisse better. By looking at Judd, Marden and Twombly we can understand Pollock better. Every generation has to learn this for themselves. If an idea is to last, every generation has to make it their own.

Posted by: Arcy

If only Warhol had done portraits of paintings of Zen monks... Posted by: Arcy I hardly see art as a form of pure competition sport amongst artists (did you notice how I stated that Rothko has no heir, this isnt some "kill the father" to ascend the throne situation). You are mistaking comparisons to competition (I'm a historian so we like to compare and contrast artists). That said, all cultural activities have some competitive element for finite resources (cash, esteem, media attention, museum wall space) it's impossible to deny... besides it's good for artists to feel some pressure. I merely see some artists like Marden as a little safe, there is nothing wrong with that but I do feel he is a somewhat hermetic artist who has been refining a good painting practice rather than an artist who has redefined painting. Goals = Outcome I doubt Marden has even wanted to redefine painting. That might be smart because I'm not even sure painting can be redefined now. Artists like Grotjahn, Davie and Mehretu each add something but none of them redefine painting either. It probably isnt possible (but it doesnt keep them from doing worthwhile things). Rothko was particularly interested in "volumes", which seems to be what Davie is interested in too. Also, though Rothko tried to redirect the discussion away from color every time it was brought up I feel he had to be concerned with it... he painted too many works that are extremely sensitive to color to discount his attention to it. I understand Rotko's defensiveness at the time to being labeled a colorist but the man did protest just a little too much....Today loving color for color's sake isnt a crime like it was in 1967. Things are a bit depressurized now for painting, it isnt seen as the ultimate visual art form, just one of many. It is kinda nice because it allows the genre to relax in areas it was too uptight for 30 years ago. I like younger painters like Carlos Estrada Vega too... by painting on magnets he built some interesting compositional freedom into the old grid painting genre. In conclusion I simply doubt Marden a little. Of course there is something noble and valid about the old brush and paint can, I'm just not certain that Marden is the premier example of that genre right now. I don't discount tht Marden is very good, but I do doubt he will be talked about like de Kooning and Rothko have been here. Is he a benchmark like they are? Will Terry Winters, Grotjahn, Davie or Mehretu fare the same? It will be interesting to revisit in 50 years. Posted by: Double J Okay, if we are just talking comparisons here, and how history will see some artists 50 years from now, then let me reiterate. I too think Marden is "very good". I don't believe Davie or Grotjahn or Mehretu or Winters or Marden are "benchmark artists". Gerhard Richter, Ed Ruscha and Cy Twombly might be. But maybe the whole notion of signifigant moments and major players is an anachronism. There is certainly enough written about post historical Post Modernism, pluralism and the conflation of high and low. I guess I'd like to simply talk about impact. Scully does it for me. Double J. Did you see the show at the Met of his work? If you did or have had any opportunity to view his recent stuff, you might concur. I was astounded by the work.and many people seem to agree.- every huge painting in it was in the collection of a major museum. Candidly, a lot of what European painters have been doing the last few decades feels stronger to me than what I see being done in the states. Of the Brit Sensations, Gary Hume's work continues to knock me out. I feel Damian and Tracey are just...sensational. The Leipzig school: Neo Rauch. The Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp: Luc Tuymans. And of course Daniel Richter and Peter Doig, Interestingly, a lot of this work is figurative. But then Callum Innes - see the new Cantz book on him.

Posted by: artworker Didn't see Scully at the Met, maybe that work might convince me too. Ive seen a # of his shows and liked them well enough... not life changing like agnes Martin. Ruscha is great. I think Hirst is doing well, I liked the skull the moment I heard about it. Emin always seems to impress me. Agreed the Europeans seem to be more interesting. Daniel Richter is a personal favorite... a lot better than lets say Tim Eitel. Rauch and Eric Schnell are pretty darn good too. I like spatial things so Schnell is my favorite of the Leipzig bunch. I'm a big proponent of pluralism... anything that claims to be "post anything" especially "history" is suspect... like the dot.com boom's "new economics". so post historical? It might be easier to not eat or breathe. I think we are in an interesting historical moment where a lot is up in the air.... and with the internet decentralizing media it's made it all very democratic... or at least open. I sense a good grasp of these times from Daniel Richter. Also, (completely off topic) is Furnas trying too hard? Posted by: Double J Why do you think that the work of painters like Peter Doig and Daniel Richter are better than what is going on in the U.S. right now? Thisnext question is a little bit of a conceit because I am fully aware that both representational and abstract paintng are two extreme sides of the same spectrum. Every painting has a little bit of both and it is only the amount that changes from painting to painting but you get my drift. Second question (possibly related) why do you think that the quasi-representational painting is more interesting than abstract painting? Is it the reassertion of the narrative? Do we like to look at human bodies? Vanity? Posted by: Arcy Well I dont think representational is more interesting than non. In many ways I think its interesting that they arent a divided camp like they were in the 70's. I like Tomma Abts and I liked Cecily Brown more when she had almost no discernable figuration... back in the late 90's. I think figurative/narrative work is easier to sell. Posted by: Double J Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)