|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Richard Mosse's "The Enclave" at PAM

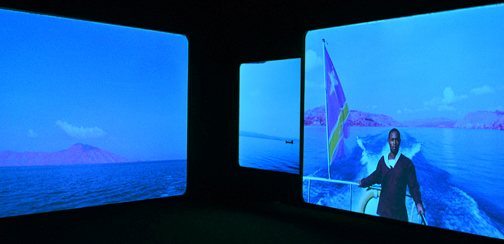

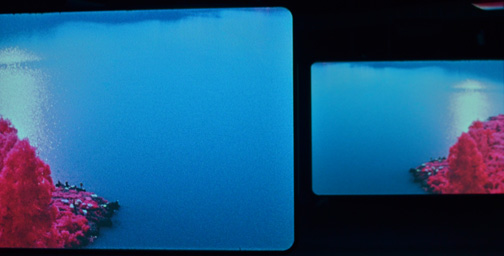

Yet, in Richard Mosse's "The Enclave," now extended at the Portland Art Museum through April, we enter into a paradox. What is in front of us is both truth and fiction, beauty and horror. We walk into a room of arresting unnameables, a corridor of exquisite contradiction. To enter into "The Enclave" is to step into a reified memory: out of time yet exceptionally visceral. The double-sided screens of cinematographer Trevor Tweeten's footage let you look but do not let you escape, and the addition of Ben Frost's minimalist audio compositions create another sensuous dimension of influence. The reception of this work cannot be anything but physical; we are swept up and consumed, against our will, a mimicry of experience to that of Mosse's subjects. Ultimately, it is the formula of the trope of horror: the juxtaposition of the sublime with the absoluteness of impending doom, and for which nothing can be done. The result is a pathos bathed in adrenalin. There is the woman, the child, the perfect beauty. We are about to lose it, like sand falling through our fingers, in the infinite and timeless way of warfare-for-what and Jason. No, no, no, no you say. Don't open that door. Don't walk into the forest alone. Don't close your eyes. Don't let your guard down. Not even for a second. Please. . .Be careful; there is so much danger here. The future of Mosse's subjects seems to hang in the atmosphere of the work like a sniper, buzzing in the soundtrack like a live wire. And here we have Mosse. 5.4 million lives lost in the Congo and to see it, to really see it, we need a man to be as crazy as this man, to turn the trees magenta and give us a bit of theater. We need an artist not bound to anything but himself to go in and charm villains wanted for international war crimes. He needs the freedom of a lawlessness that defies every agency in charge of feeding us our news and information. He needs a body of work he cannot think himself out of. He then needs to receive enough attention for this work so that it travels. We go to the museum. We open ourselves to these images. We are shaken. We become less ignorant. And while Mosse's premise is not fiction, "The Enclave" is theater. The conundrum within this work is not in the radical nature of its themes nor its methods, but that the lines are blurred between journalism and expression. What exactly does Mosse want to express? And for whom? Why is this psychedelic document featured in this place, the museum? How does it function here? These questions hang in the atmosphere when exiting the show and follow you through the rest of the museum. The various exhibitions and works here span a breadth of time unfathomable to one life, and that time coupled with distance is a spectrum of consciousness that is simply not housed in any other building or institution. The museum becomes a touchstone of human experience. Suddenly, "The Enclave" jumps onto the timeline of art history and settles in. We use art to tell truths that politics and society do not allow to be voiced. Art still creates a platform for those that have been silenced, even if that sound is not issued from the mouths of the silenced. "The Enclave" is Mosse's elegy in the name of humanity, his fuschiaed flag raised to the rest of the world in order to make poetry from an atrocity that is still virulently raging. The freedom found in art is not only protected but lauded, and this freedom often allows a story to be told in a way that is more powerful than the most accurate and detailed documentation. "The Enclave" is as much nightmare as it is paradise, as much reality as it is facade. We enter as audience and leave as witness.

Posted by Amy Bernstein on January 21, 2015 at 14:35 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |