|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Richard Serra  Richard Serra (2012) photo & interview: Paul Middendorf Set for an encounter with the art and the man I scurried into The Menil Collection to attend the meet and greet press event for Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective. There was already quite the crowd forming, so I made sure to get a quick glimpse of the show before the rooms filled up with people. Here is a short description from the Menil Press Release Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective is the first-ever critical overview of the artist’s drawings, as well as the first major one-person exhibition organized under the auspices of the Menil Drawing Institute and Study Center. The exhibition - which opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, traveled to San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), and now concludes at the Menil Collection - traces the crucial role that drawing has played in Richard Serra's work for more than 40 years. Richard Serra Drawing: A Retrospective is co-curated by Bernice Rose, chief curator emerita, the Menil Drawing Institute and Study Center; Michelle White, curator, The Menil Collection; and Gary Garrels, Elise S.Haas senior curator of painting and sculpture, SFMOMA. Installed in reconfigured galleries at the Menil, the exhibition opens on March 2nd and will remain on view through June 10th. This landmark traveling exhibition brings together more than 80 works, including 41 Installation Drawings, large framed works, and nearly 30 of the artist's notebooks. The exhibition begins with a series of sketchbooks filled with his notations and daily sketches under glass. A record of over thirty years of mark making, acting as a visual artist statement about Serra’s practice and ongoing rituals. The Menil had much more freedom with the presentation of this retrospective than its previous home, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Unlike the SFMOMA, the Menil Collection structured the room sequences and flow of the doorways specifically for Richard Serra’s drawings. Each drawing either commands the space around it or bounces the viewer’s attention from one wall to the next, connecting the rest of the drawings in harmonious energy.  Abstract Slavery (1974) I wound through the works of Serra’s first show at Leo Castelli Gallery (Abstract Slavery 1974) and to the ending with (Two Corner Cut: High Low 2012) a magnificent site-specific drawing on both the left and right walls as you enter the final room. The dueling shapes fill and block your senses at the same time, as it appears to pull the proceeding floor up to the ceiling. As my first visit was during this busy press shindig, I aggressively blocked to the door so I was the only one to experience this room. For as simple as it first looks, the drawings almost vibrate within the room. My eyes focused and unfocused, constantly trying to find the balance. The visual weight of the two drawings appear to be causing the whole room to sag. After a few minutes with the final set of drawings the crowd was weaseling into my space so I was back to work. The show was designed to run you back through the show, as if to give the viewer a second take on Serra’s works. A refreshing change from the usual exit-through-the-gift shop-path. I took in as much as I could and proceeded back to the beginning to get my spot for the talk and walk through with the curators and Richard Serra himself. Serra presented his show with great energy and vigor. He shuffled us from room to room and demanded each of us understand how they were made and how to view them. It was very crowded with photographers, videographers, and writers, but Serra made sure everyone got a chance to view the works. If the room got too cramped, he made half of us leave and move into the next room. Richard Serra didn’t lack in insight and was open to answer questions and eager for heated debate. With that being said, don’t impose religion or spirituality upon his works. It didn’t go so well for the poor woman that asked him about it. After the show, I was delighted to be hustled off to the library for a private one-on-one conversation with the man himself. Although maintaining the frame of a man at his age, he immediately took control over the room. He is a great speaker, has bold comments, and stands with his concepts. We sat down and as I was getting my recording devices situated he took my notebooks to A. Look for drawings and B. perhaps see what sort of traps I may be setting for him. I reached for them but he slapped my hand away. It’s Richard Serra. If he wants to take a look around, then no search warrant is needed. After all this is his Drawing Retrospective at The Menil Collection, and me…I have a notebook, a stolen pen, and a cheap sports jacket.  Two Corner Cut (FG) 2012 at The Menil Collection Paul Middendorf: I wanted to chat about your take on drawing. Your philosophy is greatly different than most. Hearing your talks, interviews, some of your recent book signing discussions, and your Charlie Rose conversation, I learned some interesting tidbits. One of the things I wanted to talk to you about was your practice of carrying sketchbooks around for over 30 years… Richard Serra: Probably over 40. PM: What is your take on those drawings in your daily sketch as to the drawings that we see in this exhibition today? RS: The drawings in the sketchbooks are notations and are really done for my own benefit to record where I have been at a given moment and a given time. They are like daybooks or diaries, but rather than written text they are drawings. I have been doing it all my life. It’s my way for me to keep in touch with places, space, and experiences as I go through my daily life. Some of them are interesting. Some of them, like when I was in Egypt, are continuous all the way through, detailing the sites I have been at. Some of them I actually think of as continuous, made as books to look at, where there are series of drawings that designate one subject or one theme. More so than not, they are really like diaries, where there is writing and drawings and drawings of different kinds. Sometimes there are rigging notations. Sometimes there are drawings or thoughts about sculptures as they are being put up. Sometimes there are drawings of paths of sculptures, spaces and places, topographical drawings. Whatever comes to mind, Notations about measurements? Things that I have to recall. PM: Well, these are some of the terms I have heard you use a lot: “the mark-making,” “the student work,” “the notations,” “the daily notes,” and “the studies.” At what point do these cross the line into your final drawings or do they? RS: No, I think the daily notebooks are a resource like a diary to remember space, place, and time. But they do not signify the way to move into a drawing that I would think deal with invention in the terms of drawings. These are more like simple notations that have cartoonish aspects to them or a traditional drawing notational aspect to them. I do not consider them in the same way that I consider drawings that I make to exhibit—which take on a whole different meaning for me, because as soon as you put a drawing for exhibit out in the world you have to consider everybody else who has ever made a drawing. What the meaning of the invention of language of drawing has been. And I am certainly not going to find that in the notations that I have made. I have tried to apply a certain kind of idea about the manifestation of drawing in its most simplest of terms. Mainly that matter imposes itself in form on form. So if you really pay attention to what the matter is, whether it is paper or paint stick or charcoal or whatever it is that you use, if you pay close attention to that material, and the manifestation of the material, it will lead you to its own invention without having to go to a correlative outside. Without having to go to a representation of something else.

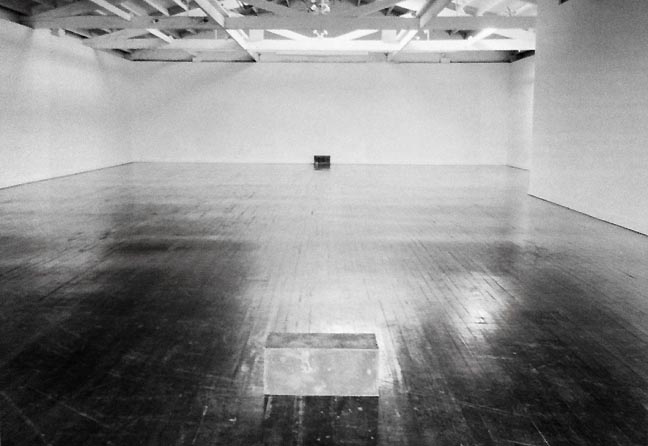

Out of Round X (2009) PM: With that being said, do you feel that these drawings in this show carry more weight than the sculptures or vice-versa? Do you feel that these drawings are representing a 2D aspect of your sculptural work? RS: [The drawings] don’t have anything to do with my sculpture. They are an autonomous body of work that deals with the context of where the drawings are made, and in that sense, they are not three-dimensional. They don’t configure volume like the sculpture does. They don’t configure path like the sculpture does. At best what they do is they re-delineate the space in the architecture to make a space within the space of the architecture that is different in kind than the architecture. They are always adhered to the wall, not in three-dimensional space. Even though in the last room they are on both walls and they create a space between them. It’s not the space of sculpture, it’s still the space of architecture. It’s a drawing space and the drawing delineation of architecture. It’s about the containment of the container. It’s not about placing somebody inside the container that changes the volume of the container by its physical manifestation. These are drawings. These are not sculpture.  Two Corner Cut (2012) and Richard Serra PM: They still act as installation as well. There is a grey area… RS: They are installation drawings, but I don’t think they have anything to do with sculpture. I made films and people called them sculptural films. I always thought that was an oxymoron. PM: Was there a point at which the drawings moved from being drawings to being installations? RS: The first show at Leo Castelli Gallery ( Group Drawing Exhibition, New York, Feb 23 – March 31, 1974 ) was the first body of drawings that I showed which were, Abstract Slavery and Zadikians. Those where the first installation drawings that I showed and those are what I considered my first drawings. Up to that point I was doing what everyone else was doing. I was making charcoal drawings on paper or paint stick drawings on paper that were figure/ground reversals that dealt with either plain or shape, but I didn’t think, until I got to the context of the space. When I started putting linen on the wall and started cutting it in relation to the architecture [then] the drawings really started to define an area, which I thought was more progressive than what I was doing. I thought what I was doing, albeit, I could do well with still dealing with an out more conventional drawing. It’s what most people will do. I have to explain something. I don’t try to make drawings first and then make my sculptures. I think a lot of artists do but I don’t do that. I am a model builder. I start by making models and then I go from the models to the sculptures. The drawings are an autonomous body of work. So I don’t make drawings that depict my sculpture. In the notebooks there are notations of drawings that sometimes after sculptures are made, but I don’t consider them drawings. They are notations. PM: So those drawings strictly live in those daily notebooks and are sometimes shown in this setting where they are all laid out? RS: In these three venues, it’s the first time I have every showed notebooks in my life. I’ve never shown them before. PM: Do you feel as though they act as an artist statement for the show itself or are they being displayed as works? RS: I thought what they would do, hopefully, was to give the visitor a grounding on who this person is as he goes through is daily life or as he goes through the years of the retrospective. What does he do on the side besides putting these drawings in the room? What are his daily notes? What is the memory of him recording of his events? You could go from Machu Picchu, to Von Schantz, to Iceland, to a sawmill, to wherever and you can see that’s what this person is about and his relationship to what his daily life is about. These are the drawings that he makes other than that. So [I] can see it as peeking into someone’s diary. They are not made with the intention of showing. They are made as private references. I don’t sell them. I will give them to a museum, probably Yale.

Richard Serra's Railroad Turnbridge (1976) on diplay in 2011 at YU in Portland PM: Changing courses slightly I wanted to talk about your films a bit. In 1976 you filmed the Railroad Turn Bridge in Portland, OR. I know you were working with some of the mills there and what else took you to that particular location? RS: I wasn’t working with the mills there. There was a center there. PM: PCVA! The Portland Center for Visual Arts, with Mel Katz and Michael Russo. RS: Yes and there was a woman there too. She went to San Diego and I can’t remember her name [Mary Beebe]. She was the main driving force there along with Mel Katz and Michele Russo. I showed some sculpture there, but at the same time I got completely fascinated with the fact that Portland Oregon had more bridges in a ten-mile radius than any other place I had ever seen. So I started going upstream. I had camera with me, a little Eclair camera. I had gotten to the railroad turn bridge and it was cloud covered. So there was no sun at all. And I looked through the viewer of the camera, and it appeared that I could reduce this turn bridge into a mechanical toy that would pirouette with in the frame. I thought that there was something fascinating about being able to the span of this enormous bridge and as it turned and opened up and looked down that river. To be able to use this frame of the panning at its edge of this section to be able to pan the landscape as it would swing back and lock. Then the train would go over and a train would come back and the bridge would open and close again. I thought that this had the potential to deal with the movement of the frame within the frame and I could use the landscape and the bridge to frame itself. I thought, that because there was limited shadow, that the structure that would occur within the minutes of the evolution of the film was something that I could see. I knew that if it came out on film once I got it developed, that I was sure there was something there. There are very few cuts in the film, probably about a dozen. I went back to shoot that film in Portland every time I would go back to the West Coast, and I made reasons to come to the West Coast so I could come up to Portland and shoot it. I probably shot there about seven or eight times and edited to a ratio of about ten to one. So a lot of it was thrown out. I was quite happy with the simplicity of the film. PM: Did you end up showing that at PCVA or did you just show sculpture? RS: No I didn’t show it at PCVA, but I did show it later and I showed it often.  Unequal Elevations (PCVA 1975, now in the Guggenheim's Panza collection) PM: Out of curiosity what did you show at PCVA? RS: There were two blocks at the end of the room. Very small. Probably a foot and a half by about ten inches at either ends of the room and it dealt with the simple elevations within the room. Someone wrote in the paper, “It was beneath contempt.” [Richard Serra shakes his head and laughs] PM: It sounds like a Portland writer. Did you do any drawing while you were there? Did any drawings come from that experience? RS: You know I went to this place in Portland. I don’t know what it was for, but there was this enormous pile in this yard of very large boulders. I don’t know what they were for, and I did a lot of drawings there. I actually hurt my back climbing over them. There was just this field of enormous boulders. They must have been eight by ten feet and all stacked. I don’t know what they would have been used for. I also remember I went to this place where they built boxcars. It was called Gunderson. So I went there and made drawings. PM: What a monumental experience this is for you to have finally the retrospective of your drawings. As I go I have just two final questions for you. Why is it that drawing tends to be overlooked in art history? Maybe you don’t feel that way at all? RS: I do feel that way. I feel that people always think of a drawing as a subtext to something other. They always feel that the drawing was before the painting or the drawing was before the sculpture so it was always something insignificant. It wasn’t something in or of itself as an audience of itself. If you ask me I would rather look at Van Gogh drawings than his paintings. I would rather look at Seurat’s drawings than his paintings. And I would rather look at Cezanne’s water colors that his paintings. I feel that you learn more about how one thinks by looking at their drawings rather than their paintings. In fact, color sort of resists gaze. Drawing does not. PM: Ok one final question for you. Should the art world now refer to you as “The Man Of Steel?” [Richard Serra laughs and shakes his head] RS: I wish they had never made up that moniker. [More laughter] I am Superman. PM: Thank you so much for you time, and again, congratulations on your exhibition. Posted by Guest on March 15, 2012 at 10:31 | Comments (1) Comments As far as Serra's memories go of his "discovery" of the railroad swingspan bridge that became the locale and subject of the film, they couldn't be more fabricated and false. I began that film before his arrival in Portland for the PCVA show, and after we met there during the installation, we became friendly and found we had similar visual interests in heavy duty industrial structures. He asked if I had a car and would show him some of the stuff in town that turned both of us on. I took him to the bridge and showed him the cinematic power of the framed rotating images it produced (I had already made friends with the bridge tender). I discussed the film idea and what I had already done in super-8, but lamented the lack of funds to do it right. He responded with enthusiasm and said we should do it together and that he had the financial resources. I borrowed 16mm equipment from a friend (who can corroborate this) who was a well known news cameraman for KATU and Richard and I went back to the bridge to film. He knew next to nothing about filming, and I set up and ran the camera while we both rejoiced at the unfolding power of the bridge, trains, ships and surrounding landscape in movement and repose. We were set to meet in NY and begin editing what we had, prior to additional filming back in Portland. I got there on one of my frequent trips hitchiking or hopping freights cross country and had a hard time getting ahold of him...which puzzled me. Eventually I had to climb up his fire escape and come through the window of his loft and wait for him to return. His response: "I'm a famous artist, and this is too good to share with you". An early lesson in how some artists treat others...to be contrasted with those who are generous to a fault. Although furious with his usurpation of my film, there was little I could do to get it back. It was only some years later when I owned and operated the premier sculpture rigging and transportation service in NYC that I confronted his dealer at the time, Leo Castelli, when he asked me to move something of Serra's. I told him the story and refused to move the piece until I at least got credit for the film and a copy. He promised to try, but pleaded with me not to upset the famously irascible Serra and let him handle it. He managed to do this and the showing at YU last year is that print... To this day the biggest loss from this episode is that the film that we would have made together never happened, and the bridge (the longest double track swing span in the world at the time) was subsequently destroyed by a ship on its maiden voyage and replaced by the present lift span. While the film that he did make is interesting, all its power derives from the intrinsic reality of the location, and is actually diminished by his relative lack of skill as a filmaker... Posted by: pdxh2o Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)