|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Okwui Enwezor

PORT: The challenge is balancing the ability to think about and consider one's audience while coincidentally maintaining the integrity and honesty of one's own creative voice. Enwezor: Yes, but one cannot only be introspective. One cannot only make work only for oneself. Ultimately, a work of art has an audience, even if the audience is one of which is you. This means there must be a critical boundary you must set up in order to objectively view one's own work; to not simply be an admirer of your own creations, but to be someone who thinks productively and critically in front of that work. It is important for artists to have confidence in their own notions and proposals but not to become overly invested in the opacity of art, based on, "These are MY thoughts; you take it or you leave it." I never accept as an absolute given that the work or set of ideas proposed by an artist can only be enabled by the agents of that artistic law. PORT: And that is something that one must constantly battle and consider. . Enwezor: And negotiate. That is something that the artist gives up, gives away, something of their own power. Yet it also means that the greatest work is able to withstand the ways of testing its integrity. PORT: For much of your career, you've acted as curator to various institutions around the world. How do the day to day activities of a Dean of Academic Affairs differ from those of a curator? In terms of organizing the education of art students versus educating the public, so to speak, in a large exhibition? . . Enwezor: Well for one, running a school is, in my view, no different than running a department in a museum. Obviously, there are different considerations that one brings to each task. To make an exhibition is also an educational project, yet rather than knowing who your audience is, it is an unknown. You have people who are deeply informed, and you have people who are amateurs. You have people who are mainly tourists, and you have people who are deeply purist. In an academic environment, the structure is guided by a number of principles, and the principles are really to make certain we have some fundamental competency that must be part of the learning environment. So my task, day to day, is to make sure that those competencies are utilized and tested, in terms of political innovation and in terms of new forms of teaching that address the multiplicity of the more political, social, and cultural experiences of our students. We want to kind of tap into the set of rigorous set of initiatives that makes learning, teaching, and producing art something that is fun but also challenging. So, while my work is administrative in that sense, it is also deeply intellectual. I think that beyond the administrative part of that work, what I value the most in being a dean is the intellectual work involved in making sure that we continue to attend to the notion of the institution as a place of higher education, as a place of thinking, and as a place of debate and analysis. My day to day is really involved in making sure that my colleagues, with whom I work very closely in various initiatives involving the curriculum around the classes and around new methodologies, have the tools necessary to make their job accessible to the students. PORT: Concerning the nature of the institution, Do you think museums and other various arts institutions are evolving at a comparable pace to the velocity of contemporary living?

PORT: How do you perceive the museum or gallery in this context? Do you believe they provide somewhat of a sanctuary and catalyst for critical thinking and learning for the public at large? There has been quite a lot of debate about the role of the museum in the breadth of contemporary society. Where does it exist? Admission prices, quite often for big shows and the like, often keep much of the public at bay, which seems counterintuitive. Enwezor: Museums, first and foremost, have a cultural role to play. To go to an exhibition at a museum is to be within the context of the redistribution of cultural capital. This is what is literally before you. However, there are very specific things that one gets to understand about the nature of the artistic object and what artists do. This needs to be learned. The artwork, while being a very specific creative model, is also an epistemological model; it has so much information in it that we cannot always have access to it without the kind of careful work that curators do, that museums do, to make those works accessible to the general public. Hopefully, the audience, by going to museums, not once or just occasionally, but as part of their cultural education, do learn things about the world or the society in which they live. I wouldn't say that art is always a reflection of the society in which it is made, but it is in a certain sense a refraction of parts of that society. Collectively put together, one thing next to the other, you begin to piece together this complex mosaic of thoughts, of experiments, of proposals, of inventions, of innovation that all, cumulatively not only enlarge our understanding of the value of art, but also have the capacity for cultural, political, social, and dare I say, spiritual renewal. So museums have a very important and powerful role to play in this regard. What I disagree with is that there is a tendency to think that it's ok to give the movie theater ten dollars for a bucket of popcorn, but that the museum should be free. How many movies do people watch every single year? And then add it up to the number of times they go to museums. . . it's very different. What I generally do is take out a membership at the museum in the city where I live in order to support those institutions. For the price of membership where you can go to the museum as much as you want in a year, it is literally, pennies. If it's just going to be an occasional trip to the museum, then it becomes expensive, but if you are someone who is deeply interested in art, and you might not know anything about art, my recommendation is to take out a membership at the museum. You not only gain access to the museum itself, but you gain access to all of the varied programs they have to offer. It is also a way to make a civic commitment, to show that art and culture matter, in modern economic times. PORT: I wanted to touch on something that you said earlier about works of art perhaps not necessarily representing the entirety of society but being somewhat of a representative refraction of it. Do you believe that when we look back on this time period, the last thirty years, that we will be able to say that this period's art was, as the fields of archeology and art history would have us believe, an accurate record of our experience? Do you think that we will look back and believe that this art was the voice of the people, of this time? Enwezor: I don't think that art is capable of being the voice of the people, and I don't think that art wants to be the voice of the people. The contradiction in this way of thinking is how can the present constitute a history? To think of contemporary art in historical terms is in itself a contradiction. To be contemporary is not to be on time; it is to be in time. It is to be current, 'in the moment', literally speaking. Of course, one can reflect on the artistic paradigms of the last thirty years and try to make sense of what has transpired. Something I have noticed is that contemporary art has indeed become more heterogeneous and more resistant to movements, even though there have been different movements which have emerged in the past half century: pop, minimalism, post-minimalism and so on. So you could look at the last thirty years and notice that what is very impressive about contemporary art is its capacity for regeneration, its capacity for historical citation while coincidentally re-engineering the ways in which the art object is constituted. So when we say the last thirty years, o.k., the spirit of the 1980's, in which there was a kind of return to this very grandiose, egoistic, conventional authority of the human subject, and, at the same time, there were these other forms of practice happening alongside those larger movements. You had appropriation going on and, concurrently, the vestiges of identity discourse emerging. All of this implies that in any given moment in the practice of art, there is never simply one specific paradigm, but multiple, competing sets of ideas within the artistic landscape. There is never just one particular dominating theology. One might have the greater visibility culturally and institutionally, but this doesn't mean that this is the only valuable system of engagement of a particular point in time. When I look back today, I think we are in a moment of rethinking of what the models of contemporary art should be. We've made it through the period of the great patrius of contemporary art, such as Damien Hirst, the sort of grandiose, rhetorical work which does not occupy a large mental space yet takes up a lot of physical space. I think the economic recession may yet bring about a rethinking of that artistic form, and what I would argue is that there are vestiges, at this moment, of what I would call the politics of form that are on the verge of emerging: younger artists using humble objects. I will also call this the politics of disaggregation. This politics of disaggregation is a model of unbuilding the grandiose, rhetorical work. This process of unbuilding is something I am currently interested in, in seeing how it manifests itself in various segments of the artistic scene.

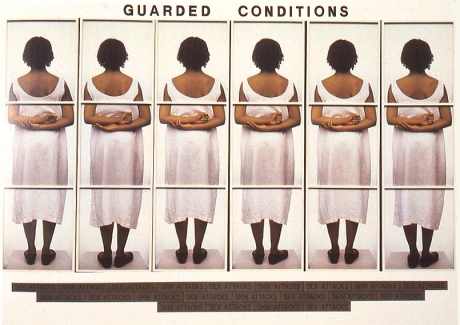

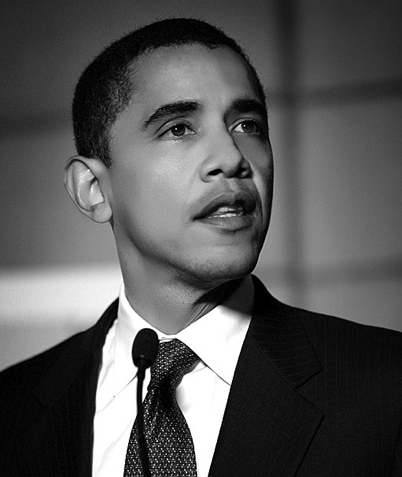

Enwezor: It depends. It is very interesting that over the last several years that it has been precisely thinkers that have not been art historians that have really been influential in helping us think about works of art: a philosopher like Jacques Ranciere, for example. . . a philosopher like Giorgio Agamben, who may not necessarily be talking about art but the kinds of things he talks about, his philosophical terms, come very close to the things that artists are struggling to do. The current decade is a decade where theory was basically jettisoned. The late eighties and early nineties were at the height of the theoretical implications of post-modernism. Theory was given a great deal of license and was mobilized in various ways to help us understand the goals and the characteristics that artists were constituting for the reception of their work, for the understanding of what they were doing. You've seen, for example, artists like Lorna Simpson, and the ways in which the image becomes, not simply just an image, but a series of complex signs which have very deep social relationships to the ways in which the figure, the feminine figure, the black figure, has been deployed in a Eurocentric, Mediterranean culture. Theory gave a kind of buttress, if you will, to enabling us in thinking productively about those shapes in thinking, in art making. But, over the last few years, I would say that theory has not been first and foremost in the minds of artists. The return to beauty and beauty opposes theory, the return to painting and painting is aesthetically pleasing. . . So we are constantly engaged, especially over the last half century, in a process of constant historical return. And thus there is always a place for theory in art. There is always a place for philosophy. But to the larger question that you pose regarding where criticism and theory are today, I will say it is not very good. There are simply less and less places where criticism can actually be practiced. There are fewer publications devoted to serious thinking about art; most are not just simply academic. There are less academic journals where a certain type of art historical practice can occur. There are fewer popular magazines where a certain type of criticism can occur. Newspapers are laying off the art writers. . .. So, there is a crisis. There is a crisis of discourse. What we need to think about is where can the discursive dimension of contemporary art be located today? What happened in the nineties, with the emergence of the curator, is where this discourse has shifted to the catalog publication. This, for the curatorial field, seems to have absorbed part of this loss of critical debate. I don't know if this debate takes place in catalogs, because often catalogs become almost like advertisements for the art. They become almost like a press release rather than a critical examination. There is a tension there.

Enwezor: I think that while we may claim that art has become pluralistic and heterogeneous, the context within which that can be engaged has shrunken. Also the broadening of the media has changed that. I think that the context of artistic participation is bigger; there are more museums. There are more galleries. There are more things. More, more, more of everything. When the art world was smaller, you could read five different magazines and feel as if you were immersed in a very intense discussion, but today contemporary art is global. There is not a single publication that has the capacity to encompass the richness of the field. In a sense, one has to read as thoroughly as one can. Even if you have all of the time in the world, it's impossible to capture all of the different arenas in which this is happening. Yet, there is a lot of debate taking place in different parts of the world; there are publications in every corner of the world. To take a perspective in which the art world is the center at a time when global culture is completely off center is to miss the fact that there are multiple contexts that are really generating new positions. PORT: As a curator with such a global resume, do you see a zeitgeist in the midst of contemporary art or does geography still grant us somewhat of an autonomous experience and identity? Enwezor: I don't know if there is a zeitgeist, and I will be careful in even trying to identify one. But it seems to me, in the last several decades, that contemporary art has become part of the global reality. More art is made across the world, by many more people than ever before. I will give you an example, in 2008, there were eleven triennials and biennials in Asia in the months of September and October. In Korea alone there was Busan Biennial, there was Seoul Media Biennial, there was Guangju biennial, In China there was Shanghai biennial. There was the Guangzhou triennial. There was the Nanjing biennial. There was Taipei Biennial. . .You can go on and on. So, when you think that, in this region alone, in one month, there was such proliferation of art, and when you think of the size of these cities. . . Beijing: 12 or 14 million, Shanghai : 18 million, Singapore as a city-state, Sydney, Seoul, Busan, and so on. What we have is such a massive potential for enormous throngs of people seeing this art. I took a group of students on a trip last year to about five of these cities in Asia and also to the biennial I curated in Guangju. While Guangju is a city of about 1.4 million people, the audience for the exhibition was 425,000 people. Now that is more than the Whitney Biennial. Are all of these people really invested in contemporary art? I think not. But contemporary art, in some of these, what are called transitional societies, is a novelty. So, free exhibitions in those areas may not have the same level of sophistication but nevertheless, they inform people about what is going on. In Shanghai, on the day we arrived, they had a ticker of the number of visitors and there were already 670,000 people who had seen the exhibition. Now that is enormously important for contemporary art. How do we make sense of all of this? Some magazines in the United States try to do an overview of all of these exhibitions. That can only mean that there is no one singular form of criticism that can appropriately engender the intricacies of all of these, except to basically say the state of contemporary art has become a phenomenon of global scale. I imagine that, given this complete dispersion of artistic senses, the value of contemporary art will be different depending from the space in which you, as an audience, engage with the work. PORT: With such enormous audiences and numbers of artist participating in these exhibitions, they have been criticized as 'spectacle'. . .What do you make of this criticism? What do you believe is the true purpose of these biennials? Enwezor: Well, first and foremost, a critique of biennials as spectacle is already, for me, not so interesting because I have not really read yet an intelligent encapsulation of what people mean by spectacle. It presupposes that art should remain in this exclusivist domain of privilege. The fact of the matter is, in the mid 19th century, more people went to the British Museum on weekends than you would normally find in museums today. People went because the museum was a novelty. It was a social gathering place. I would not criticize an exhibition because so many people showed up. Why would that be a bad thing? However, I do understand the worry, and the worry is that contemporary art has been sucked into the mode of entertainment. We do a great disservice to audiences by assuming that they learn nothing from going to these events. Biennials are event driven, and therefore they have the effect of seeming like spectacle. There is no doubt that they have the quality of spectacle. But the critique of spectacle in this sense, for me, seems not to take into consideration what I mentioned earlier, which is that these societies in transition are places in which we are only witnessing the first generation of the emergence of a middle class. So, let me simply speak about my experience in Asia, in China and so on. The cultural revolution in China destroyed the public sphere; it destroyed institutions. There was no place where artists could show. Today, the public in China are hungry for whatever. They go. That can only mean that they are interested in art. The difference is saying whether or not that exhibition is pandering to that spectacle. That is where there is a genuine argument to be made. Either within the curating or if the artwork produced becomes entertaining, populist, etcetera in order to generate curiosity. Now there is an argument to be had, in which the critique of 'spectacle' is valid. I know that popularize the notion of the bienniale form as spectacalism, which I suppose was intended to be a derisive term. I think there were many reasons why this emerged. It was not simply the fact that we had an exponential growth in the number of artists that were practicing, but that there were not that many more places where they could all be shown. A biennial is a temporary exhibition which then turns into a bridge in order to enlarge the context of artistic determination and presentation. And as temporary structures, they were responding to the context of contemporary art in ways that museums are not equipped to. I think that what it did was to create new, discursive spaces for the reception and the presentation of contemporary art. And it made sense, because biennials are literally global models. And it made sense that they emerged precisely at a time when globalization became so prominent. One other thing that I would like to argue is that, contrary to what many people think, most biennials are not large scale. Most biennials are not spectacular either. Look at where most of these biennials are and the budget that they work with. They don't have enough money to really be spectacular. Let's face it, it's very different to work in Documenta, with a five million dollar budget and the Whitney Biennial with a two million dollar budget. The scale is very different. Venice is also different, from say, SITE Santa Fe, which is a biennial too, but which could never be spectacular, even if it wishes to. Its context is smaller. Its means are smaller. There are so many other things that intervene in the workings of many of these biennials that mitigate against them being spectacles. PORT: When you wrote about Lorna Simpson's work, you touched on the notion of politics and aesthetics as being inextricably linked within a work of art. I believe in your writing, you described these two facets as being formed like "Siamese twins", to quote you. Do you believe that this is true of all art, that its politics and its aesthetics develop simultaneously, concomitantly? Enwezor: No, they are not inextricably linked. What I was going after in discussing Lorna's work was forms of what Toni Morrison would call 'American African Inference'. There is no way to divorce the aesthetics of race from the politics of race. PORT: What do you think the election of Barack Obama might do to this marriage of politics and aesthetic in regards to racial perception? Enwezor: Nothing. PORT: You don't think the unbelievably prolific presence of his face everywhere in the global media might have even the smallest influence? Enwezor: No. Absolutely not. It makes us feel very good. I hope it doesn't, but, I think there is a danger in the fact that Barack Obama is the president which may make us feel as if the job has already been done. Look at institutions in this country, museums in this country. Take a poll of all of the major museums in this country, and tell me how many have directors who are non Caucasian? How many have chief curators who are non Caucasian? It is much more feasible for Barack Obama to be the president of America than it is for Barack Obama to the director of MOMA in New York. It's amazing. PORT: So you don't think the image of his face being as prolific as it is might have any influence on the image of the black male in America? Maybe as the catalyst to changing the notion of what Frantz Fanon would have described as the 'other'? Enwezor: Well, Barack Obama is first and foremost a post-colonial phenomenon. So yes, this somewhat touches on the issues of race in the United States. However, it is very important to remember that there is a part of Barack Obama that is being obscured. He is part African. He is not African American. Think about this, in 1961, when Barack Obama was born, his father was not an immigrant, he was a foreign student. Kenya was not even independent. Segregation in the United States was still an issue. So there are many complex historical issues that are tied up in the personality of Barack Obama which we can use as a cipher, not for the normalization of race, but for the normalization of the complexity of race. I think that Barack Obama is really wonderful to watch. This young couple is of my generation. Obama is older than me by just two years, and he is the president. I see Obama and there is a constant shock of recognition. I know who Barack Obama is, not individually, but generationally. You can see that in the way he thinks about the world. It makes sense; there is a clear generational shift. This is why I feel he is a post-colonial president. It is interesting that you mention Fanon. Obama was born in the midst of the post-colonial transformation of the world, and that is in his D.N.A. PORT: Would these great thinkers, (such as Fanon) feel as if his being elected was a notable progress for what they believed in? Enwezor: I think that Obama is a step in the right direction. It is hugely positive. At the same time we could ask ourselves, where else in the world could this have happened but in America? But yet it is important to say that well, America is not the first place that this has happened, after all, Fujimori, the son of Japanese immigrants was the president of Peru, but we don't see that as momentous because Peru is so small in comparison. And that in America, the politics of race has been fundamental to the identity of the American self. This is why the election of Barack Obama is such a big symbol and has made him a cipher of the aspirations of many people. He will perhaps make many people who feel imminently qualified to think that they can be candidates for important positions. We will have to wait and see, but, I think, the mold has been broken. We have to make a new mold. PORT: Who do you think of as your general audience when writing and curating? Enwezor: Oh dear, that is a question I ask myself repeatedly. I begin from the point of view that there are three fundamental audiences I'm interested in. When I curate an exhibition, I am as much speaking to my peers as I am to historical precedents. I use those two relationships to develop an image of an unknown audience. At this point my focus can be based on a series of historical and intellectual attributes that then have to be unknotted for the public to really understand what the exhibition is trying to say. I am as much in conversation with the historical precedents, not to correct them, but to address them, as much as I am in conversation with my colleagues, with the field, as such. Finally these considerations allow me to say well there is something new I want to say to the public. Otherwise it becomes narcissistic, as in, 'this is my great voice, and it is a gift'. This is not for the public at all. It is a complex melange of conversations that leads to these multiply connected audiences. PORT: What do you think is the role of the curator within an exhibition? Enwezor: Well, first and foremost, for me, a curator is not merely an organizer of exhibitions, even though that is a part of what they do. A curator, in my view, creates the platform that advocates and enables ideas that he or she supports and endeavors to create the most hospitable environment in which those ideas will be understood. It is enabling and working with materials that are challenging, provocative, and that have the capacity to influence the way in which we think about the human condition. All of those things are bound up in what I do. I feel that my role as a curator is fundamentally intellectual, but that doesn't mean that it is intellectual in the sense that there isn't any possibility of communication across historical, economic, and cultural experiences and differences. I organize my shows with all of these things in mind which is why maybe sometimes people think of my exhibitions as political, but they are not. It's just that the representation of art and its institutionalization is deeply political, and I do not curate an exhibition with the kind of naivete that art trumps politics. There are so many different political social factors mediating who gets to be in the canon, who gets to be collected in the museums, and having worked in museums a number of times, I understand what the internal conversations are. I know what the anxieties about certain forms of art are. PORT: To not think about all of these factors is to run the risk of isolating art for its own sake, and make the claim of denying its socio political importance, relevance, and implications. Enwezor: That is why for me, to present an artwork in public has deeply ethical implications. Because why should we look at your art, no matter how great it is? PORT: In view of the recent economic recession, we witness the collapse of a lot of our capitalist economic architecture. Much of the ideals of our motivation in terms of an economic society have imploded, soufflé style unto itself. Will the art market mirror the financial market in its implosion as it has its explosion? What will this mean for our ways of seeing? Enwezor: It will have a temporary affect. Artists will have to adjust to what their expectations are. Galleries will have to adjust the ways in which they instrumentalize the works of art to generate more profit, and I think the bubble, as you say, has collapsed. Whether this is a return to order is a different question. Yet I think that the moment that the market rebounds, it is almost inevitable that it will be back to square one. After all the new expression is the market collapsed; nobody ever asked whatever happened to all those great works by Schnabel and Salle. You don't see them in museums any more. So will the same kind of backlash happen with people like Damien Hirst and Koons and so on? I don't know. But I think that, certainly, there was already a sense at the very height of the market, some forms of resistance by artists towards this rhetorical, flaccid gesture. And there artists now who are working in the kind of opposite vein. This is what part of my lecture will be on this evening so that we can talk about some of these emergent relationships. After this height of the market, the M.F.A. became the new M.B.A. So bankers and artists. . . PORT: Which is why I wonder if this recession will distill some of the inflation? Will it distill the critique? Will art making continue to be next to banking as a sort of capitalist endeavor? Enwezor: Well I don't think that art making was ever a capitalist endeavor. The marketing of art is a capitalist endeavor. But we must be very careful that we do not demonize the art market. The art world as such is a complex ecology. There are many different aspects playing a role in our ability to have access to the most challenging ideas that artists are putting forth. The art market is one of the entities that enables that, that supports artists so that they may make a living, to produce, and so on. The museums represent another one. There are many different mechanisms that enable art. My fear is that a collapse of the market might not simply just affect the ability of dealers to sell work, but that it might cause the erosion of resources that support experimental ideas that support younger artists. We've already seen that. Now there are very few philanthropic support networks dedicated to the arts, and this inevitably effects institutions. Institutions become more conservative. They become less daring. So the implications of this economic recession have the possibility of being very severe. I am very concerned for my students and their ability to have confidence that they will have a chance to present the public with their work. You know, we critique all of these biennals, but when they disappear, what replaces them? I can tell you that without these biennales, the shape of the contemporary art field will be very different from what it is today. We have the opportunity to see a greater number of artists than ever before. The recession affects the support for those networks in the same way it affects the support for the art market, in the same way it affects the support for the acquisition of works by museums. The endowment of curator postions is already affecting the support for research. Institutions have taken out moratoriums on programs which require research and travel. . . How do we gain an understanding of whatever this new art that is being made? How do we gain an understanding of this work? This is far more complex for me, in this sense. This is the concern I have. PORT: Do you still write poetry? Enwezor; Oh dear. No! Well. . . Tim Griffin and I occasionally exchange poems with one another. Posted by Amy Bernstein on April 24, 2009 at 0:16 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |