|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

When Donald Judd Came to Portland "It isn't necessary for a work to have a lot of things to look at, to compare, to analyze one by one, to contemplate. The thing as a whole, its quality whole, is what is interesting. The main things are alone and are more intense, clear and powerful." -Donald Judd in his essay Specific Objects

The founders set three objectives for the PCVA. First, they wanted to exhibit the best contemporary art that was being done in all regions of the United States. Second, they tried to stimulate commnunity awareness of the diversity and excellence of contemporary art through both exhibitions and others programs. Last, they wanted to bring the artist themselves to Portland to discuss their work. Over the 17 years they were able to put on an exhibition schedule that would have been successful and relevant even to MoMA. To give you some sense of the caliber of artists that have spent time in Portland because of the PCVA: Carl Andre, Yvonne Rainer, Lynda Benglis, Sol LeWitt, James Rosenquist, Daniel Buren, Ed Moses, Allan Kaprow, Frank Stella, Donald Judd, Alice Neel, John Baldesari, Chuck Close, Richard Serra, Chris Burden, Dan Flavin, Robert Irwin, James Turrell, Lucinda Childs, Andy Warhol and Agnes Martin just to name a few. It is hard to think of an arts institution that would have been more dynamic and relevant during that time period. The PCVA put on ten to fifteen visual arts exhibits every year as well as equal number of dance, music, and theater performances. There were a lot of things that were different about the PCVA and a comparable institution would not be created on the East or West Coast until the Dia Center was created in the late seventies.

Mel Katz and Mary Beebe, the director of the PCVA at the time, had been talking to Judd about an exhibition at the PCVA since the fall of 1973. The PCVA had extraordinary timing because this was one of the last site specific sculptures that Judd produced prior to having a large retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa which was curated by Brydon Smith. A large catalogue raisonne of Judd's work, which was also edited by Brydon Smith, was being published in 1975 in conjunction with the retrospective at the National Gallery. As it turns out, PCVA's timing might have been a little too good. The cutoff date for the catalogue was work produced prior to May 1974 and so the installation at the PCVA was excluded from one of the main references on Judd's work.

In a letter from Donald Judd to Mary Beebe and Mel Katz in late February, he expresses his concern that the work that would be in the show in Portland might be damaged during transportation, packing, or installation/ de-installation and proposed using an art handler in Los Angeles, Doug Christmas of the Ace Gallery, that had also worked on the Frank Stella show a year earlier at the PCVA. Perhaps the logistics of the retrospective and the concerns about working with work that Judd had already produced had become too much because by early March of 1974 the plan had evolved again so that the show would now be two large plywood sculptures that might be able to travel to other venues after the show. This would have been great for both the PCVA and Judd. Judd would have got a small travelling exhibition of sculptures in the United States at the same time he was having the large retrospective in Canada and the PCVA would have got partners in the other venues to help cover the fabrication and transportation costs, an arrangement that had already worked well for the Frank Stella show. The PCVA approached both the Denver Art Museum and the University Art Museum at the University of California at Berkeley to see if they would be interested but it seemed like their exhibition schedules had already been filled.

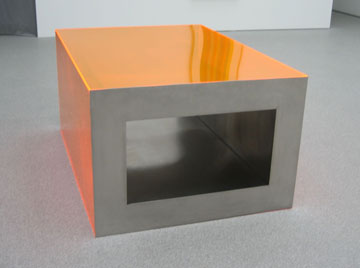

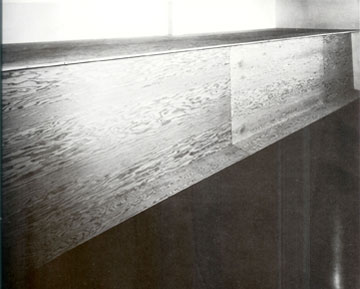

Judd had already been using unpainted plywood sculpture as installations, rather than sculptures since early 1972. In a way, it is in the warmth of the plywood pieces that Judd comes closest his goal as having a sculpture that is a simple and direct as he saw in the paint of Pollock's paintings. Judd thought that one of the most interesting things about Pollock was that paint was used as a material in its simplest and most natural state. The raw, physical properties of the paint as a material were enough. In Judd's plywood sculptures, because the plywood grain is so apparent, the natural character of the plywood as a material can be expressed simply and directly. It is even better if the sculpture arose from the geometry and proportions of the plywood itself. As PCVA would discover at the opening, it is in the plywood sculpture that Judd walks the line closest to having his sculptures become non-art, in the same way that Pollock's paintings moved beyond what people thought was painting. Ironically, that was Judd's intention all along.

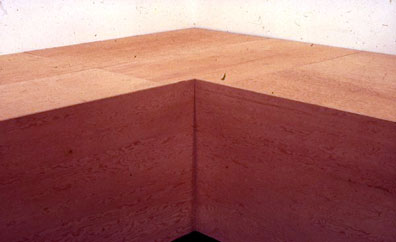

A direct predecessor to the installation in Portland was in two large plywood sculptures at the Lisson Gallery in London in 1974. In the installation at the Lisson gallery, the sculptures were large plywood rectangular volumes based on the proportions of the plywood and the specific dimensions of the space in which they were installed. The sculptures were installed in small alcoves and in one of the sculptures he recessed the front face 4" and in the other, the top is raised 4" to create a clean reveal along the top edge of the sculpture. In both cases, the reveal changes the way that you experience the sculpture.

In early 1974 when Mel Katz and Mary Beebe were still courting Judd for the installation at the PCVA, they had sent him a couple of drawings of the layout out of the space as well as photographs of the Carl Andre installation from a year earlier. Because Judd had never seen the space before and probably won't until very close to the opening, it was those drawings and photographs that were his only connection to how he might install something in that space. Early in the process Judd thought that he might be installing some of his work before the retrospective in the space, the actual layout of the space was not as important so long as it did not interfere with how his work would be viewed. When the installation might have been two new sculptures as part of a travelling exhibit, the sculpture would have to work equally well in a wide variety of different spaces. Over the summer of 1974, something must have changed for Judd, whether it was enthusiasm for the recent installations at the Lisson Gallery or he might have thought that it might be best to simply build one large sculpture that relates to the specific characteristics and constraints of the PCVA space. Ultimately, Judd must have thought that this was the best sculpture for the space. I can't really imagine Judd proposing a project simply because it might have been easier or more efficient. The PCVA exhibition space on the third floor of 117 NW Fifth was like the prototypical New York loft space: it was approximately 46'x 100', with white walls, wood floors, and large arching trussed rafters for the ceiling. There was a large skylight at the back of the space and five windows that looked out over the street below. The space was slightly "L" shaped because it was narrower closer to the street to the support the fire stairs and the elevator. The back of the space was about 8' wider than the front. Judd chose to install his work at the back of the space under the skylight. The space was wider but it was also contained by walls on three sides and was defined by the projection of the wall that contained the stairs and the elevator. Except for the sculpture, the rest of the space was left empty.

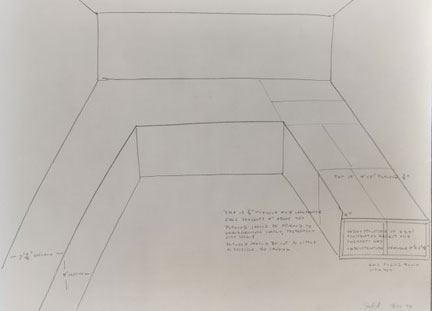

The sculpture itself was made out of 55 sheets of 3 /4" plywood was supplied by Hampton Lumber. According to Mary Beebe, the plywood was lent and then returned to the Hampton in "slightly used" condition. Judd had originally requested that the plywood would be marine grade plywood which would have made the budget 5x more expensive. The sculpture has three sides that starts and stops from elements in the architecture of the room. The long south side started at a column 3/4 down the length of the gallery, turned the corner on the short west wall and continued around on the north wall until it was flush with the projection wall that enclosed the stair and the elevator. The dimensions of the installation were 65'-4" on the south wall, 46'-1" on the west wall and 40'-6" on the north wall. There was a subframe built of 2 x 4's that ran around the room to support the plywood. Interestingly, the layout was arranged so that the 2 x 4's would only have to be cut to two lengths 7'-11 1 /4" and 3'-4 1 /4". The 3 /4" plywood was AC Exterior and cost $9.12 per sheet and 2 x 4's at 8 ft. lengths cost $.97 each at the time. Judd's instructions were simple: -Face is 3 /4" plywood 4' x 8' that is to be installed lengthwise. -Edge projects 4" above the top. -Plywood should be attached to understructure simply, preferably with screws. -Plywood should be cut as little as possible. No sanding. -Understructure of 2 x 4's to be constructed in the easiest and cheapest ways. Understructure measures 3'- 7 1 /4". There are two of those instructions that stand out for me. First, it is interesting that he did not want the fasteners to show on the exposed side. The sculpture was not to be a construction, it was to be the raw experience of the characteristic properties of a material. Without the fasteners, the sculpture is one object and it reinforces the monolithic feeling of the sculpture As is often the case, what seems to be straight forward and easy rarely is. In order for the plywood to be attached it means that besides short screws or nails, everything would have to be fastened from the inside. The second instruction that was interesting was that he asked that the plywood not be sanded. Plywood which is made of a series of thin veneers in opposing directions is very easy to sand through but I think that the Judd did not want the piece to look too "finished" or "hand crafted." These are industrial materials that are handled in the most straight forward way as possible. The installation in every sense of the word was very much a specific object.

In what might seem like a straight forward installation, the plywood is asked to perform some seeming contradictory roles. The grain of the plywood brings flattens out the surface of the plywood, we do not get the benefit of any spatial ambiguity that we see in some of Judd's metal sculptures. The volume of the sculpture is defined by a taut flat surface. Interestingly, it is the plywood grain that helps to flatten any residual spatial depth of the surface of the sculpture. An example would be, that if the sculpture was made of aluminum rather plywood, depending on the lighting conditions, the viewer might be hard pressed to determine exactly where the sculpture starts and stops. The sculpture is all surface that is sometimes stretched and folded to become a volume. The plywood describes as stiff, monolithic, rectangular volume that is contrasted with the 4" projection of the plywood on the front face. The projection reveals 3 /4" width of the material and undermines the solidity of the plywood box. Incorporating everything that Judd learned from Pollock and like all of Judd's best work, the physical properties of the material remove any implied illusion of space. Everything is flat surface, even when it is three dimensional. The installation becomes a real object in a real space that provides a real experience but nonetheless is somehow more than the just the sum of its parts.

Unfortunately, I was never able to experience the installation first hand and so I have to rely on photographs but it seems to me like those who experienced the installation would have to relate to the sculpture as a real object rather than as "art." The plywood on the front face which has the 4" projection which is lengthwise is amazing because the plywood is presented as itself but in a new context that turns it into art. The plywood exists with a natural dimensions 4'x 8' and you can see its 3 /4" width on top but at the same time it relates to the space in the way that you had never seen in another piece of plywood. It is the equivalent to the raw, liquid paint at the bottom of one of Pollock's cans. It is an expression of the potential of the material properties of a given material. It is the way a line of plywood relates to the volume of a room that I feel like I get closest to Judd.

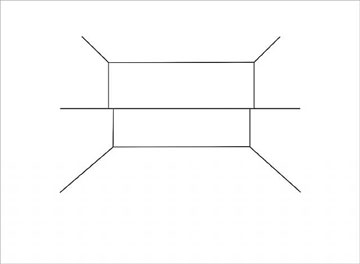

In 1970, Judd made a sculpture that was made of 15 units of galvanized iron. Of course, it was simply called Untitled, 1970 and I think that it was done for the lobby of the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York but I think it isin Marfa now. Of the fifteen units: 12 are 60" x 48", 2 units are 60" x 41" and one is 60" x 13". The galvanized iron plates that can't be more than 1 /2" thick and sit flush to the vertical face of the wall. It is Judd's equivalent to a sculpture by Carl Andre but it is on the wall rather than the floor. The galvanized iron redefines the plane of the wall by projecting it slightly into the space of the room. The installation is incredibly shallow but redefines the perception of the room. It literally changes the location of the wall. I would bet at the time that the galvanized iron was available in 60" x 48" sheets which is the module of the work. More importantly, the galvanized iron was cut to fit the walls of the Castelli lobby on three sides, that is why there are three different sizes to the units rather than just one. The installation of this sculpture in New York was a precursor to the ideas of that were to lead Judd to the solution for the installation at the PCVA.

Judd probably chose to run the sculpture on three sides because it would give him three different end conditions as well specifically addressing architectural elements that define the PCVA space. On the long south side, the viewer would be able to see the whole sculpture in profile except for the part that is hidden by the column which marked one of the constraints of the installation. In the middle, because it turns the corner on both ends, it is completely continuous and on the north side the sculpture is allowed to transition into the wall that houses the stair and the elevator. For being such a simple idea about how to define a space with plywood, when it is applied to the actual context of the gallery, the result is very complex. Judd effectively takes the main characteristic of the space, that it restricted in front and open in the back, and makes it the driving idea behind the installation. The piece starts at a column that breaks the wall plane of the main space and ends at a projection that significantly narrows the front part of the gallery. This is a more sophisticated than the installations at Lisson that were about enclosing a volume of space in a two alcoves because it is a relating to idiosyncrasies of a much larger space that you can actually walk into. The installation is less about an object and more about the redefining the experience of the space of the entire room. The object becomes the space and the space becomes the object. It is impossible to separate one from the other.

When Judd arrived in Portland he was put up in the Benson Hotel at 309 SW Broadway by the PCVA. After a few days of helping to oversee the end of the construction of the installation, Mary Beebe took him to dinner with Bruce West. Mary Beebe thought that it would be great to show Judd a little bit about what Portland has to offer before the opening that the next night. It was the beauty of the Northwest that made the exhibition attractive to Judd in the first place. Over dinner in what has to be one of the funniest stories in Portland art history, West asked Judd if he would like to go river rafting the next day when he goes with Robert Peirce and David Cotter. Now keep in mind that it is mid-November and already getting cold, but Judd amazingly said yes, so maybe Judd was desperate for a vacation after all. The next morning they picked up Judd at his hotel and he looked like he just bought a whole new outfit from a U.S. Outdoor's store. He climbed in the car and they headed up to the Clackamas river. West who was trying to assure Judd that they knew what they were doing kept telling Judd over and over that Bob Peirce has ridden this river many times. It worked until Bob, who did not know he was being made out to be the expert, looked up and said "This is such a great part of the river, I don't know why I have never run it." Judd looked up at Bruce and gave him a big smile.

Even more amazing is Judd was not the only famous person that they took on river rafting trips. Although Roy Liechtenstein turned them down on their offer, Roy's wife Dorothy who was the reining beauty of the New York art world said yes not once but twice. They took Dorothy on multi-day rafting trips on the Rogue and the Deschuttes rivers. Although the later presidential candidate's wife Joan Mondale declined their offer, their motto became "entertaining famous people in precarious ways." Judd by all accounts had a great time and took them to dinner afterward. As one can imagine by his homes and studios in Texas, he really enjoyed being in the outdoors. After one last check of the installation, Judd went back to the hotel to get changed for the opening. Some people say that Judd, who is of Scottish descent, wore a red plaid kilt to the opening and other says that it was a red plaid suit.

"Donald Judd is an internationally known sculptor living in New York and Texas. Although Judd's work can not be clearly categorized, he has been a leading and outspoken figure in three major contemporary schools of thought: minimalism, formalism, and conceptualism. He has designed a work of unpainted plywood specifically for the PCVA space and he will be in Portland to oversee its construction. His work has been included in many important exhibitions throughout the United States, Europe, Australia, and Japan. This will be his first one-man exhibition in the Northwest."

The exhibition of the Judd installation was just one of many excellent exhibitions at the PCVA. After Carl Andre, Frank Stella, and Donald Judd had exhibits and had a great experience working in Portland, the PCVA slowly begin to create a reputation that would open up many doors in New York. In the early seventies, the art world was a different place. The artists were more accessible as people. You might meet them in New York, write them a letter, or simply call them up. An artist would come to Portland to have a show because people were interested in the work and not because it was necessarily the next step on the ladder in an artist's career. In a way, the PCVA was successful because it was in Portland and not in New York. An exhibition gave the artists the ability to see their work in a different context but since Portland moves a little slower than New York, there was more time to think about the work or talk to other artists and students about an installation. Portland gave New York artists what they needed most: time.

By the mid-eighties the art world was changing again and the PCVA closed its doors when the grant money from the National Endowment for the Arts began to dry up in 1988. At some point a threshold was crossed when energy and enthusiasm was no longer enough, even for an institution with a track record like the PCVA. There is even a funny story where the PCVA was planning on having a show for, at the time, and upcoming young artist until the artist's New York gallery began demanding a catalog that would have cost as more than the budget for the entire show. An exhibition in Portland was not seen to have as much return on investment for the dealer. Portland was no longer seen as having unique value for an artist. The slow pace of Oregon life and the beautiful environment were no longer valued to an art world obsessed about making the next big sale so it became part of a long list of interchangeable places where an artist might show their work. Just as the PCVA changed Portland, I would like to think that the it PCVA could not have existed anywhere except here. The people here are hard working, resourceful and always willing to push the limits about what might be considered possible. The PCVA, like all of the people who were involved and like Portland itself, it has always been one of a kind.

Most of my writing has been about art that I experience firsthand. That was impossible in this case and it is a credit to the PCVA that so many people that were associated with the institution would remember their experiences so fondly and would be willing to share their experiences with me. I would like to give special thanks for all of the people that have been incredibly generous with their time in answering my questions and helping me with my research for this article: Mel Katz an East coast transplant that wanted to create a little bit of what he loved about New York in his new home of Portland. He was one of the PCVA's founders and still one of its greatest advocates. Mary Beebe, Executive Director of the Portland Center for Visual Arts (PCVA) from 1973 - 1981 and now currently the Director of the Stuart Collection at the University of California at San Diego. Mary Beebe has been extremely generous with her time in answering all of my numerous emails in the nicest and most informative way possible. Bruce Guenther, the Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Portland Art Museum for being supportive of my research at the museum. Debra Royer Library Director of the Portland Art Museum who was always extremely helpful in pulling things out of the PCVA archives and scanning things for me on short notice as well as providing me with crucial background information. Jane Beebe owner of the PDX Contemporary Art Gallery in Portland who helped put me into contact with Mary Beebe. Bruce West is an artist in Portland who often volunteered at the PCVA and who took the famous picture (with Bob Pierce's camera) of Judd going down the Clackamas River. Paul Sutinen co -chair of the Art and Interior Design Department and Director of the Arts Programs at Marylhurst University who wrote about the Judd installation as an art critic when it was on display and gave me some great things he had written on Vito Acconci, Carl Andre, Donald Judd, and Robert Irwin. In an interview he sent me with Carl Andre I came across one of the best quotes I had ever read. It said: "There is no one true way except that way which is true for one's self. My way does not invalidate the way of anyone else." Bob Peirce who is an artist in Portland who often volunteered at the PCVA, and lent his camera to Bruce West to take a great picture and most importantly, kept Judd safe going down the river. DK Row and Drew of the photo archives at The Oregonian for helping me find a little bit of Portland history that everybody could remember but nobody could find. Posted by Arcy Douglass on April 27, 2008 at 22:57 | Comments (5) Comments A very significant post. Judd is really important to a lot of Portland's scene (of all ages) and needless to say Portlanders shouldn't settle for less when we talk about raising the bar. This was the bar. Also let's arrange a rafting trip too that's a class IV rapid that's pictured there! Sure, Chinatown is pretty much hallowed ground but it shouldnt keep us from pushing forward and taking stock of our history. Some are pretty bitter about the PCVA's demise... I dont blame them but we have to take the legacy in a positve light. For example it's important to note how many of Portland's current arts leaders grew up aesthetically and honed their tastes around the PCVA and it's why they have such high standards. I just love the historical plywood tie-in too... all of these artists must have seemed so strange but that's the ride you take with art. Anything too familiar or academically obvious is already dead. Sure, the art world is different now and part of the PCVA's demise but the sense of risk taking discovery is important. Ignorance of such history is a crime.... thanks Arcy. Also, does anyone have something they would like to share about their PCVA or Judd experiences? Posted by: Double J Thank you so very much for writing this piece -- really a pleasure to delve into.I sincerely hope you will continue writing and posting more pieces like this. Posted by: Namita Wiggers I was incredibly pleased to come across this rigorously researched, but also quite personal, account of Portland art history. Thanks Arcy, it was fantastic. It would be great to see many more articles such as this make their way onto PORT in the future. Posted by: Sam Gould Thanks Sam I'm a historian so PORT has always had this in mind... though it takes someone passionate enough (with time) to tackle a historical subject. I knew Arcy would be stunned when he saw the PCVA archives... Actually I think Arcy's piece on The point is, we have a history and its a good idea to understand it. For many the PCVA was simply too painful too revisit but I think we have to move beyond that. Even the Chinati Foundation took notice. So yes we are working on more of these... Also, If anyone has a pet subject they'd like to tackle just contact me at Jeff (at) portlandart.net

Posted by: Double J Great article. And thank you for mentioning Debra Royer, the head librarian at PAM. Ms. Royer is one of the coolest people I've met in the arts community since coming to Portland years ago. When I worked downtown, quite often I would visit the PAM library on my lunchbreaks. She has always been helpful, willing to look up items or point out new books or media aquisitions. I don't get downtown much anymore, but the PAM library is the only must-visit place on my list. (The Yamhill Pub maybe a distant second). Ms. Royer deserves much credit for heading such an amazing resource. Posted by: Sean Casey Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)