|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

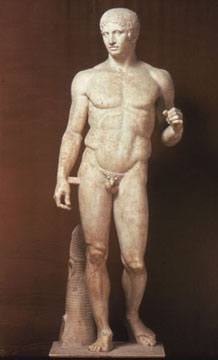

On Form (or from Polykleitos to Janine Antoni)

Is that really what art is about? Is art about what we know or what don't know? For me, one of the greatest things about twentieth century art is that we finally came to grips with understanding the best things in art are the things that we do not know, maybe it is what we can't know. When we go into our studios, do we go to work on things that we already know and reinforce our perceptions about the world?

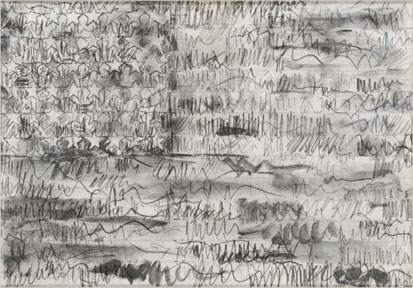

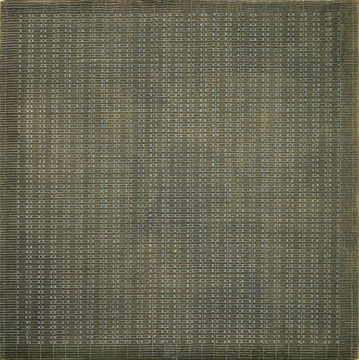

"When everything in the world was a possibility I only tried three or four things over and over... I didn't take advantage of that supposed freedom, and once I decided I was going to have relatively severe limitations, everything opened up... I was never happy making interesting shapes and interesting color combinations because all I could think about was how other people had done it... Now there is no invention at all; I simply accept the subject matter. I accept the situation. There is still invention. It's "how to do it," and I find that, as a kind of invention, much more interesting."

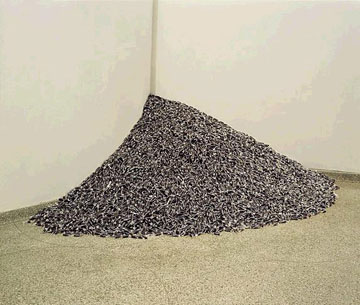

The last work that I wanted to talk about is Janine Antoni's Saddle from 2000. I thought it was fitting to end an essay about form with a work that is about the emptiness in form. Saddle is about presence and absence. You can feel her presence in the work but she is not there. It is a little strange that you associate the contours of her body with her skin, but in the work you do not see her skin it is the skin of a cow. So there is a spatial and tactile dislocation that is central to the experience of the work. It is not a representation of skin but real skin, except that it is not hers. The skin was part of a living breathing animal not long before it came part of this sculpture. So you thought that the work was about her body but is it really about this cow, whose natural shape that you don't see but whose skin defines the work. Never having touched the work, I can imagine that it is very stiff like a dog's chew toy. So sooner or later you realize that you really do not understand about the human body. Once we understand something, we change again. Is the expression of ourselves about the form of the body or our memories and associations of it? If what we value does not have a form, how can it be perfected?

Posted by Arcy Douglass on February 18, 2008 at 18:19 | Comments (6) Comments De gustabus non est disputandum. After nearly 5000 years of reasonably vibrant intellectual activity, we can finally agree that when it comes to matters of taste, there can be no dispute. Perhaps now it is time to move beyond the simple awareness that perceptions are relativistic and ask what our cummulative perceptions - and the fact they change over time - mean. In mathematics, the measurement of a specific instant is often meaningless, but a measurement recorded over time can provide a wealth of meaning. The rate of change (acceleration) of a rate of change (velocity) is far more interesting than the static reality that a car is on a road. That a calculus of aethetics exists is certain, in my mind, even if no one has defined it precisely . . . yet. And what thoughtful writers and thinkers on art (which you clearly are) convey to the rest of the world is their sense of awe at how their perceptions change and transform over time. What we discover, as well, is how difficult it is to discuss such matters, because they are complex and the terms we use can be so difficult to define. What is beauty? Is it an inate property of the object, or a measured response in a viewer? A 14 year old boy will respond with intense emotion and feeling to a grotesque drawing which adults will find juvenile and immature. Is the image beautiful - to the boy, absolutely. The question then becomes does the object have an intrinsic beauty? Your essay seems to lean towards a post-modern interpretation that would imply that, no, there is nothing instrinsic to the object, it is only about us, or as you suggest, the artist. I would dispute this and say that it is both. There is an intrisic value which is not created by an artist, only revealed; and the only way to discern the value is to observe how the object relates to a variety of viewers over time. The work which evokes a strong response in the widest range of individuals has tended to become the art which people have come to call the "best". I approach such terms with extreme caution, for I cannot help but answer in response, "best for what?" Best for developing a discerning mind? Best for overthrowing a fascist regime? Best for inducing meditative awareness? For art does all these things. Agnes Martin once chided an interviewer for not asking her what her definition of art was. Her answer - "the concrete manifestation of our most subtle feelings". A perfect definition for her artwork, but Picasso? Not such a subtle guy. The reality is that art is complex, and its production is a physical manifestation of our intellectual wealth. It is also fundamental, a pillar of our awareness of reality, along with its twin, science. Your writing, which contributes to a sturdy support of that pillar, is always much appreciated. Posted by: Amsterdammer What I appreciate as a historian is the fact that we have run out of intellectual whipping boys. What I mean by that is stylistic/ideolgical choices like: Beauty vs. Ugly (same thing really) ...are all acceptable simultaneously in any mixture today. I.E. the 70's pluralism that got hijacked by the idealogues of postmodenism is now back. Also, rhizomatic forms of communication like the internet have kept this pluralism alive and all channels have remained open since the interheck got big in the late 90's. Nobody fears/worships Greenberg anymore... he's useful Posted by: Double J Thanks for your comments Amsterdammer. That is an intersting analogy with 14 year old boy. I wonder if the drawing would be unlocking something that already exists in himself, even if he might not realize it at the moment. To continue the analogy, what happens in a few weeks or months and he gets bored and moves on to something else. What happens when the drawing can no longer unlock that same intense reaction? If the beauty was in the work, wouldn't that mean that it would always illicit the same reaction no matter what the circumstances. I think that it is we who change and not the work. When we respond to art, we are responding to the feelings that it creates inside of us, the actual object of the art is only vehicle. I have been getting a little frustrated with beauty lately and maybe it is latent in this essay. For me, beauty has become a stick to keep people in line. Beauty has turned into something to reinforce the status quo. Beauty does not exist without the cultural context to go along with it or maybe we keep adding the cultural baggage to beauty. I think that there will be an essay coming up on this soon. One thing I did learn is that we look at the world very different than Polykleitos did. As beautiful as my wife is, it has hard to imagine that the human body is the embodiement of the highest perfection found in nature. I am not sure that we see ourselves that way any more. Also Polykleitos derived a set of proportions that he thought embodied perfection but could never be found in a living human being, only in a carved statue. I would like to think that we are more willing to embrace the world and the experience that is around us. The good and the bad. In the difference between Polykleitos and Antoni, although they are both naked I think Polykleitos is more visual and Antoni is more tactile. Maybe we want to see with our hands now. Maybe we do not trust the perfection of our minds anymore. Posted by: Arcy It seems to me that this essay is another revisitation of Kantian aesthetic theory with an emphasis on Beauty (form/feeling) and the unpresentable (the Sublime) as theories of aesthetic taste. Why is it important to apply these theorhetical constructs once again? It simply reinforces a rather reductive discourse surrounding thinking about artistic practice and experience. In a contemporary society, utilizing the Lyotardian model of the postmodern sublime as a way to think about artistic production; it elminates binaries and encourages the indeterminate. According to artist and scholar Charles Gaines, the new model for contemporary artistic production relies on a metonymic structure. Metonymy occurs by relating two non-related things together in a new context, which creates new meaning. This is a linguistic structure which can also take part in our visual language of art. Contemporary advertising relies on metonymy to function. So does (in my opinion) the best of contemporary art. Contemporary art has many interesting concerns and issues (use of the archive, new narrative structures) that by reverting to this old model of discourse seems rather backwards and reductive considering that we are not living in the 18th century anymore.

Posted by: Metonymic Thanks for taking the time to comment Metonymic. I was arguing that experience is the primary effect of art rather than beauty or the sublime. I think that aesthetics always reflects the society that it arises within. My argument was that our idea of aesthetics was not permanent or absolute but simply a construct of our society's view of what should be valued in art. The experience of the individual is primary in my opinion. The dangerous part of aesthetics is that it can be used to close off avenues of thought or experience that could provide genuine growth simply because it is beyond the theory, or it is outside what society tells us good art should look like. At the beginning of the essay when I explain that my own taste, simply because it is impossible to be absolute, must be considered fickle and arbitrary. I was hoping that readers would also apply this to the art world as whole since we are only human with a limited amount of information to work with. Because I believe that one's personal experience is primary, I also do believe that metonymy only encourages us to be to distracted from what we are looking at, as if what we are experiencing is not able to hold our attention or worthy of the expereince. I liked what that you said it eliminates and encourages the indeterminate. In your argument it is strength, for me, it is a weakness. In my opinion, in order for metonymy to be successful we have to separate ourselves from the two sides that they could be see in perspective, so to speak. You have to have distance to be able compare two things. I am arguing just the opposite. I think that the best way forward is complete surrender to the experience so that it can evolve from the intentions of the artist. Another way to look at is to say the metonymy encourages the ego or the singular identity of the viewer, so that it can have clear separation between the two objects so that it can generate an indeterminate third. In my view, if the viewer surrenders then the ego dissolves, and since there is nothing outside of the present experience there is nothing to compare it to. We are free to experience what the artist has provided for us, unchallenged. I think that metonymy is what make contemporary advertising so unappealing because after the intial exposure there is nothing for us to hold on to, we are left floating in the indeterminate. There is no doubt that at one point these strategies were successful but I wonder if we are moving away from that now. Posted by: Arcy I certainly don't think that revisiting and discussing 'dated theoretical constructs' is inherently bad or can lead to reductive reasoning about the artistic experience. After all, theoretical constructs are similar to many pieces of art in that they are static, and can be viewed with a new eye at a later date. What's more, not everyone is immediately familiar with all the world's past philosophy, as none of use posting here happened to be born in the 18th century. Combine this with the fact that philosophies and aesthetic theories are constantly reapplied and given new context when new artwork is made and I don't think that Arcy's statements come off as regressive at all. The Bible is a metonymic piece of literature. Rembrandt understood the importance of process over product. Ancient Islamic architects understood the importance of aesthetic beauty relating to architecture. Truly gifted artists have come and gone knowing this stuff for hundreds of years, but it never gets old. That's why it's so great! Aesthetics is a wildly misleading term, and if you really hack it down it ends up meaning, as you stated in your essay, the standard of attractiveness for a certain culture in a certain time. For sure people are trained by society, biology, and past experience to enjoy certain images, representations, and formal relationships. However there are certain visual impressions that are inherent in our chemical makeup, generally those reflecting the biology of ourselves and the world that helped us spring into being. Therefor, some things will probably always remain to some extent, universally beautiful (we men love our naked ladies!). Even if the conceptual elements of the work or the rationale that brought about its existence are completely laughable, the pure visual makeup of it can bring people pleasure on a visceral level. So, are aesthetics something that must be done away with? Are they simply an intellectually stifling obstacle that prey on our animal nature and obstruct the sublime, intellectual appreciation for the experience of a work of art? No! The best forms of art find a way to use the aesthetic boundaries that define them to speak out their message in a beautiful way so that other human beings can embrace these products of their labor with open arms. Sometimes the bend the rules, other times they break them. But oftentimes when a piece of art is successful, these newly redefined borders help to establish new aesthetic ideas. When aesthetics run parallel to benevolent concepts, the resultant works can foster community, respect, and dialogue within and between cultures. Certainly paring down things to their complete absolutes is a ridiculous concept in the postmodern age. However, to speak of transcending any sort of shared form of visual communication is an equally specious concept. Where you see artists defeating their preconceptions of art in order to transcend aesthetic tastes and make work that is truly revolutionary, I see artists refining and honing their own visual language. I'm not disagreeing with you, mind you. However, I think that artists are aware of aesthetic and do make use of it, however they make a conscious decision to work within their own personal aesthetic, more commonly referred to as a visual language. A great artist is one who has matured enough to pare down his or her ideas into something that is greater than the sum of its parts. De Kooning painted his first great works with black and white. Why? Because these parts were easier to assemble than the infinite choices that were previously before him. And after all, if you broaden the scope too much, it's all a waste of time anyway. We're just a bunch of little specs floating on a rock hurtling through the void, etc. Perhaps, if aesthetics and an artists 'style' or visual language are all speaking roughly of the same thing, we should consider the definition of aesthetics to be equivalent to the language of mass culture, reflecting what is arguably the least common denominator. Meanwhile, a refined visual language is like a great novel or a beautiful poem. It takes many a tool we are all familiar with, and redefines it in a way that is somehow elegant, despite containing more ideas than ever before. Conceptually, or collective awareness is ever-broadening. We've seen an explosion in artistic thought due to the fact that art has only recently been permitted to embrace any and all materials, which all come with their own fascinating and inherent meanings. However, until we're all hooked up to neural networks and don't ever have to open our eyes again, art must still exist in physical space and is therefor a slave to our own animal senses. I continue to embrace beautiful art in the same way I enjoy a delicious pizza - through my romantic, life-loving, hedonist nature. This is a fascinating topic, and I don't think that any of us could sum it up in a scant few paragraphs. However, I don't think tossing the concept aside as a 'been there, done that' sort of response does any good. It's certainly not the equivalent to backpedaling 300 years. Posted by: Owen Hunter Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)