|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Adam Stennett for Disquieted I met Adam Stennett on a sunny, Saturday afternoon in May. Seated

on a park bench outside the Portland Art Museum, we discussed the development

of Stennett's working process, growing up in Oregon, and his life in Brooklyn

since 1994. Stennett's video piece, Mouse Swimming Overhead, is featured in the

PAM

Disquieted exhibition. Disquieted closes Sunday May 16, 2010.

Adam Stennett in the South Park Blocks, Portland Or. "...you have to grab them from across the room and then punch them when you get them up close." - Adam Stennett Gary Wiseman: Let's begin with your impressions of the [Disquieted] exhibition. Adam Stennett: First of all when Bruce [Guenther] contacted me and said that he had a video of mine that he had borrowed from the collection of Ben And Aileen Krohn, and then he started telling me about the exhibition and who was going to be in it, you know, it was kind of like my dream team. So many artists whose work I really reacted to. They were already people that I had seen in New York and a lot of the work was from artists that I already considered interacting with or reacting to. If I was going to list fifty artists whose work i liked, there were several in the show. It was really exciting; It's always exciting being in a group show with other artists you have a strong reaction to. GW: Were you surprised that he wanted to show the video since, I mean, would you consider yourself a hyper-realist painter?

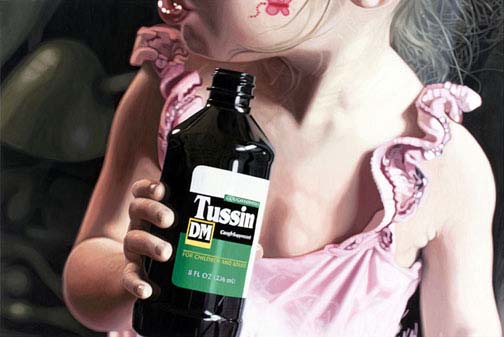

Adam Stennett. Girl Looking Left with Tussin. 2007. Oil on wood, 48 x 72 inches AS: That's the majority of what I do. I do some installation work, some video work. Its funny though... Galleries often want to show the paintings and, so far, the museums lean toward the video work. GW: It's compelling work. I love low resolution video. I have explored water and tarps blowing in the wind with video as well, these kinds of investigations, so I love watching your video. I was just up [in the museum] looking at it prior to meeting you thinking to myself, how did he do this, just on a technical level, did you have a bucket or something, and were shooting up through the bucket? Is that how it worked?  Adam Stennett. Mouse Swimming Overhead. 2004. video (DVD), edition of 9 AS: It's the first video that I ever did as a serious art piece and it came out of the paintings that i had been working on... GW: So you did the paintings first? AS: The paintings came first.

Adam Stennett. Mouse Swimming Overhead 1. 2004. Oil on wood, 12 x 12 inches GW: Ah, that is really interesting. AS: To make the paintings I work by first taking a bunch of photographs, so I usually have an idea and then I'll shoot 200 or 300 reference photographs. GW: Do you ever show the photographs? AS: I haven't ever shown the photographs as finished products but it is an important part of the process because what I set out to do isn't usually what I end up doing. It's an organic process. GW: Kind of like drawing or sketching... AS: Yes, it is a lot like sketching. And then I go through all the work and narrow it down to a few images that I think are strong or work or convey the metaphorical ideas I am trying to convey. GW: When you are shooting are you shooting in a three dimensional way? All around an object? And then when you start working are you working from a specific photograph? AS: I work from a specific photograph. GW: So you are making a painting of a photograph? AS: I am making a painting based on a photograph although my end goal isn't necessarily to make a painting that looks exactly like the photograph. But I work out the compositional aspects in photography first. So I know exactly what I want the composition to look like and then it is just a matter of the process that goes from the reference imagery through the eye, through the brain and gets translated to the paint. GW: As I was looking at your work that was the question that kept coming up for me. Is he making a painting of a photograph? But I think that your paintings are a lot more compelling than a photograph and are more effective as paintings because you work with such intention. Every centimeter is hyper-real. Highly representational of what is going on. I think that that aspect of your work makes the subject a lot more effective. AS: Well when I think about paintings, the thing that has always interested me about painting more than image is object. You know, the process I use to make a hyper-real painting in a lot of ways is a really abstract process. I try to disconnect myself from the image as much as possible when I am painting and just look at shapes more than painting an object or water or a person. GW: Ah, you're painting abstract images... AS: ...I am painting darks and lights. So it almost becomes like meditation in a way. A lot of times I work in grids from the first couple layers and then the last layer I move away from the grid. I often work upside down also. GW: You're disconnecting yourself even further. AS: Because the brain tends to fool us into thinking we know what something looks like and what I am interested in more is translating and making marks. GW: You talked about having the photograph, running the photograph through your mind and hand... AS: Also when I am painting I think about painting out what's wrong. I paint until the painting doesn't bother me anymore. So I am covering things up as much as I'm putting things down. GW: A taking away... AS: A subtractive process. Not entirely, but because you're building up layers...in building up layers they cover things up. They also let things show through, but it's a pretty abstract process. But getting back to the video, that was the first video piece that I did and I had been exploring this mouse swimming imagery, mouse underwater and I had started working with mice because a lot of the ideas I was exploring were the little things that are all around us that either we don't notice or we're too busy to notice or it's too uncomfortable to pay attention to. And things that might be trying to tell us something. It could have a little signal for us that if we'd only paid attention we could avoid something or improve something or move in a different direction. I have always been interested in the idea that if you had turned right or left or go diagonally in your route somewhere life could be completely different. That kind of idea. The idea that there are little things trying to tell us something and we're not picking up on those or it is possible to pick up on those more than we are is really something I'm interested in. Mice seemed like a good metaphor to explore those ideas because they are everywhere we are in a lot of ways. GW: Almost like a symbiotic relationship. AS: Yeah that is a good example. GW: Same thing with cats and dogs. I saw this sensationalized T.V. program about what would happen if humans disappeared. It said that the first thing to go would be the cats and dogs because they're so dependent on us. AS: Yeah, well its funny how interconnected we are. I do a lot of research when I start. GW: Yes, I have noticed that. You are very rigorous in your research process. It actually made me a whole lot more interested in what you do. AS: Well, I like to be prepared and I like to look at things from every angle to really figure them out when I am working on a new idea or piece. The more I researched mice and rats... GW: Did you read that book Rats? AS: The one about rats in New York city? GW: Yes. AS: Yes, that is one that I read. GW: I was blown away when I read the part about rats being able to fit through a hole the size of a quarter. AS: Yeah, smaller sometimes. They are incredible. GW: The ability to compress the body. AS: And I also met, along the way, a mouse and rat scholar from Princeton who wrote this book on mouse genetics. He gave me his book which was amazing. GW: The Edward O. Wilson of mice and rats? AS: Yah, he was looking at my paintings and saying, "This is an M-56 mouse", I'm probably giving the wrong number, but he knew them on such an intimate level. He was saying, "The thing that's interesting about this mouse, a European house mouse, is that over the years it has developed a taste for wine" It is basically an alcoholic mouse... GW: [Laughing] AS: ...and the reason it works in experiments so well, this particular mouse is used in experiments often is because it has an addictive personality. That's something that is interesting to me too. The human need for...the way humans are compelled to do certain things. Why or what's behind what we do. GW: That's something I was wondering about as I looked at the imagery, your choice of subject and what you are presenting. Is a mouse sometimes a proxy for a human being as far as test mice. There is one painting, I can't remember the name of it, in which there is a needle going into what appears to be an albino mouse...  Before the Accident. 2004. Oil on wood, 24 x 24 inches AS: Yes, "Before the Accident" GW: ...and then there's references to pharmacology, the further references to conspiracy, I am wondering about your relationship to those signifiers, why you brought them in? What they mean to you? I know how I'm reading them but what is your intention with this? AS: Ok. One thing I try to focus on as an artist is using every experience to influence your work and using your experience to build your work. My father was a professor of pharmacy for 35 years and is actually getting an award tonight in Portland. GW: That is one of the reasons you are here? AS: Yes. GW: You grew up in Portland, right? AS: I grew up in Corvallis, but spent some time in Portland. So I sort of grew up with this science and pharmacy background and then the idea of medicine. Most of the medical breakthroughs that happened in the last 150 years are partly due to mice and the sacrifices that mice have made. If it wasn't for experiments with mice a lot of these things wouldn't happen. I think mice are amazing creatures and incredibly important to human life. GW: That goes back to the symbiotic relationship. AS: Yes. It's also something we aren't so comfortable thinking about. GW: Yeah, a lot of people are pretty angry about it. Especially in this town. AS: Which is important too. I remember being in art history in college and the professor talking about Matisse, and Matisse saying that painting should be like a comfortable armchair. GW: That's not the case with you! AS: Yeah. I remember being, not upset, but I really disagreed with that at the time. You know I was like, "Screw Matisse" he doesn't know what he was talking about. As I got older I sort of understood more of what he was talking about but I had a real aversion to that idea. I really want my work to give people a shove to push people slightly outside of their comfort bubble. And this video piece that's in the show here was actually the first piece that I ever got protested about. GW: Did the mouse drown? AS: I wouldn't have done that piece without doing a lot of research, and in my research I discovered what good swimmers mice are. In a lot of scientific studies mice do endurance tests. GW: They research how long mice can swim? AS: Yes. Rats have been known to swim three miles. That's often how the Norway rats came to New York. They swam from the ships which were moored out [in the bay] but in these tests they have mice swim for 30 minutes, 45 minutes, which was much longer than these mice were swimming. In the video the footage is slowed down to 33% so what looks like a long time...it's more hypnotic. I was taking something that is sort of troubling and making it beautiful. Walking that line between panic and calm. That is something I was really playing with in that piece. GW: I feel like, for me, that is the most effective art strategy, something that rides that line, sets up a dichotomy between opposing ideas or feelings, like panic and calm or funny and disturbing for instance. AS: The protest was actually one of the best experiences that I have had as an artist. It wasn't really a huge protest. It was at the Bergen Museum in New Jersey. It was a small show. A mother and her ten year old son came to the show. They had read about it in the newspaper and knew that there was this video piece with the mouse. They were animal rights activists and the mother was teaching the son about being an activist and speaking out and going to something like that and they came to the opening and she introduced herself and said, "My son had something he'd like to say to you". So he said, "I don't think you should have made that mouse swim. I think it was probably very scared." And so we talked about it for about a half hour and we had an amazing conversation. I said, "It's really great what you're doing, being active and talking about things, this is one of the best conversations I have ever had about an art piece with anyone, and I am having with you, right now." GW: He was ten? AS: Ten, yeah. We began talking about, this was about the time that all the Abu Grebe stuff came out. And he was saying that the mouse looked like it was being tortured. And I said, "Well, that's an important thing for us to think about and that is part of the idea of the piece. Is the mouse being tortured? What is torture? The mother got angry then and said [emphatically], " I don't want to hear anything more about Abu Grebe. I read it in the papers. I'm sick of hearing about it." GW: Right, that is interesting. AS: I said, "Well... GW: It's happening. AS: Yeah..."That's interesting but it's good to be concerned about anything like that. I applaud you for being concerned about that, but you can't just be concerned about one aspect of it." That was a really powerful piece, but it did make me think about being misinterpreted too because I love animals and these mice I raised from baby mice. I actually bred them. I had as many as 36 mice in my studio and when I was painting I used to have them sit on my shoulder. The mice in the video are, probably about ten different mice, the mice were only in the water for about 30 seconds at the most. I would drop it in and pull it out, dry it off, give it a snack. GW: So you had a pretty intimate relationship with these mice? AS: Yes. For about four or five years I was basically a mouse farmer. [Laughter] AS: I would give them a bath every Sunday in my studio. GW: All 36 of them? AS: Yes. GW: How did you do that? AS: It was a bit of a conveyor belt process. But I got pretty good at it. GW: So, individually? AS: No, I had a little bucket that I filled up with warm water and pepperminty soap and let them splash around in there while I was cleaning their cages, anyway, we're sort of getting out there on this. But, yeah, I was very close with the mice. GW: So the references to pharmaceuticals isn't necessarily a critique then. When I was looking at the mice, there was the mice, the pharmaceuticals, and that is such a hot topic, especially in art right now like in Damien Hirst's work. AS: I never intend my work to be one definition. I always hope that it opens up more questions than it defines. But taking things that are, that will push people, or push people in a certain direction, or step outside of their comfort bubble a little bit. I think we just go through life in a kind of bubble sometimes and we don't really see. When you get pushed outside of that bubble, you are like, wait a minute... GW: I call it the moment of destabilization. AS: Yes. GW: Which is where transformation can occur. AS: Exactly. GW: That's what happened with 9/11 on a national scale. AS: Yeah, it wakes people up and it could be in a bad way or a good way. GW: Well, we automatically seek stability and if that comes in the form of Homeland Security... AS: Right. Yeah it can be dangerous but it can also be enlightening. GW: I learned that in Tea Project, I told you about before we began. I would take people out into places, and they would often not know what they were doing. These "Tea Parties" would be in public space, in a vacant lot for example. They [the people] were dressed according to a theme, they were in this unfamiliar place with strangers. So there was that destabilization, they were all on the same level, there was not really any status there, they could interact and have conversations, connect with each other, see things differently. AS: The pharmaceutical stuff is, this idea of medicine or fixing yourself or fixing your brain, or tweaking your reality. I did a show called, Off the Grid, these still lives of homemade drug recipes. GW: Yeah, I was looking at those. They are strangely disturbing. AS: I researched a lot on the Unabomber stuff. Just people who were living off the grid and conspiracy theory stuff. GW: I read on your website that he was involved in CIA mind control experiments. AS: He was definitely part of the Mk-Ultra project when he was at Harvard. He was actually a math prodigy and was at Harvard at 16 or 17. I think he was there at 16 and then at 17 started to do these experiments. He was from a lower middle class family, didn't have a lot of money, and they would pay students to be a part of these projects. There are a lot of people who think these experiments broke his brain a little bit. GW: I know of this man who did a magic mushroom trip, just one, and it triggered Schizophrenia. AS: Yeah, the mind is fragile and reality is... GW: Tenuous. AS: What we think is real is not necessarily real and our everyday understanding of reality isn't necessarily right. GW: Believe me I think about that everyday. I have no idea what real is. AS: That is something I am interested in exploring with my work. At least asking these questions or encouraging others to ask these questions. That series [Off the Grid] was a series of an unseen presence. A portrait of an unseen person through objects…like evidence. GW: It was various representations of the ingredients of recipes. AS: Yes, Exactly. GW: You had poppy seed and nutmeg, everyday household items that you could tweak yourself out with. AS: Yes, you could self medicate with or change your reality with. In a way that is part of the allure of art, there are these objects that, if they are effective, might change the way you see the world. GW: The more I go into art, the more i realize that it is totally about the artist, that individual working stuff out. AS: It is important that the work speaks to you as the artist, but it needs to communicate. When I first started showing the mouse paintings, half the people would walk into the gallery and say, "Ugh, I can't even be in the room with these. They creep me out". The other half would be, "Oh my god, I love this". And that strong reaction...I am not interested in a medium reaction. GW: Exactly. I think, as I walk around the Disquieted exhibition, and I know you are presenting a video work here, but looking at that work and looking at your paintings, which you said the video work came out of, I feel like you are one of the most appropriate choices for the thesis of this show. But you work, generally, in one of the most traditional forms of image making. That is really compelling. AS: Its a good challenge. I went into the Whitney Biennial a couple of weeks ago and walked through it again and I found myself not interested very much at all in the painting. There wasn't a lot of painting to begin with in the show, but the video work, I was really excited about it, that's really interesting. Video work has been getting a lot more attention from museums, but the collectors still want paintings. There are some collectors, but I think it takes a special type of collector to collect video. They have to be pretty confident in what they do. GW: I find that to be an interesting question actually. Because, really, with flat screen televisions you could have a... [Simultaneously] Moving painting! GW: You get so much more information. So many video artists, myself included, work that way. Thinking about everything in terms of drawing or painting, very intentional selection of what's present in the work. AS: The thing about paintings that I still love, and I will always paint, is that they're a charged object. There is the energy of me sitting there and making marks on this object. GW: For hours and hours. AS: Some of the bigger paintings are three or four months of my life, everyday. GW: You work from 8 [PM] to 8 [AM], right? AS: Sometimes...most of the time, yes. If I have a solo show that is usually the schedule that I end up on. 8 [PM] to 10 in the morning. 8 to noon, it depends. I was on a six hour alarm clock for awhile when I was really under the gun. Somehow I went for six hours of sleep a night and whenever I got that it was cool, but I didn't leave my studio for a month or two. GW: That is a pretty intense schedule. AS: But there is something about that intensity that, I feel, is almost like alchemy. There is something chemical that gets instilled into the paintings, It's sort of a weird... GW: Benjamin talked about the Aura, is that what you mean? AS: Yeah, I guess so, it's sort of a romantic idea I guess. GW: One of the questions I had for you was, "Do you think of yourself as a magician or alchemist?" I wrote that question down because, when I was researching your work, that was the response that viewers had. A response of wonder, "How did he do that? I thought it was a photograph". I had in my mind magicians pulling rabbits out of hats, and started thinking about your work in terms of a performance. AS: It is sort of like a performance I guess. I would hope that they would get beyond the idea that it looks like a photograph because that's only the first layer. GW: Exactly, but that is something that really draws people in. AS: Yeah, you have to grab them from across the room and then punch them when you get them up close, or have something more to give. The thing that is interesting for me as a painter is that everyday is different. GW: When you are painting? Even though you are doing the same action, it is like a ritual? AS: Yeah and you try to keep things similar, try to get on a schedule, try to have as little distraction as possible. That's why I paint at night because there's no distraction, it's quiet, there are no errands that you have to run. But it is always scary. Because the human brain is so chemical. You could be sitting in front of the painting and make this mark that you wouldn't make another day. So sometimes when I'm painting I don't want to stop because I'm afraid if I stop I am going to miss something or screw something up. If I'm on a roll I just want to keep working. There is a process that I go through before I start painting everyday where I get myself, it's almost like meditation, get yourself in that place... GW: While you are working? AS: No, before I start working, when I am mixing paint, I sort of like get myself in the head... GW: To a meditative space? AS: Yeah, I try to detach and make these marks. GW: Would you call it a process of disassociation? AS: Probably. Detachment in some way. GW: Which is another thing I wanted to ask about your work, something my friend Gabe Flores and I discussed, there is a lot more intimacy with the mice, but from that point you moved on to depicting humans, women with bottles of Robitussin. But they are very detached, they almost seem lifeless, the people featured in those images. AS: Well that's part of this idea of the human need to numb ourselves, self medication, this fear of feeling too much. Which is something I want people to feel through my paintings, but I also know that there is a human barrier to that and a wall that comes up when you push that. GW: There is a moment, like we talked about. A small moment. AS: And a lot of the imagery that I, sort of, a lot of what, because I'm not trying to define something with the imagery, I'm trying to open up something. A question or something... GW: They [the viewer] go away and think about it again? AS: It is usually the moment when something is about to happen. That is the moment that I am often interested in. It hasn't happened yet. It could go one way or another. GW: Would you define that as in between or liminal... AS: Yeah, I guess its an existential moment. The possibilities are open. GW: It could go either way. AS: I studied painting and writing in college and I wrote my senior thesis... GW: At Willamette [University] in Salem, OR? I was surprised when I saw that. AS: [Laughing] I'm surprised constantly. I liked Willamette a lot. It was an amazing place. I went from Willamette to New York, two weeks after I graduated I moved to New York. I had never been there, but everything that I had studied at university was happening there, so... GW: What year was that? AS: 1994. Awhile ago...15 years, 16 almost now. GW: Sorry, I interrupted to clarify there, what were you saying? AS: Oh, just that I wrote my senior thesis on Heidegger on his book, "Being In Time", it explores possibility, awareness and our everyday understanding of being in the world. A lot of my work has literary influence and philosophical influence. GW: You do so much research. Where do you look for your information? What are your top five books at the moment? AS: I used to read a lot more than I do now, unfortunately. Most influential books? GW: Not necessarily the most influential, everything we read is still there. We learn information, I call it feeding. AS: More recently, in the last five years probably, I do a lot of research online. I mean I have folders and folders of imagery that I am constantly pulling from things, I like the way this image does this certain thing that I am interested in doing. GW: Visual diary or reference material. AS: Yes, Reference material. I did a lot of crazy research on conspiracy theory right when they were talking about if they are watching your computer, 9/11, all of the wire tapping and, is the government watching what websites you go to. I was also researching things like drug recipes, do it yourself stuff. I was often wondering if there was a file being made on me somewhere. If you put all of these clues together, thinking about research as clues... GW: It starts making a picture. Do you know this artist Mark Lombardi? AS: Yeah, I like Mark Lombardi's work. GW: He read the New York Times and various news sources everyday. He kept a file of cards with information he had collected, and figured out some pretty controversial things. He represented his findings with hand-drawn data mapping diagrams and got killed for it. AS: Maybe I was thinking about someone else. GW: He was working in the eighties and nineties and I think, figured out the Iran Contra scandal among other things. AS: Oh yeah. GW: At one point the CIA came and bought almost everything he did. It was all there. That is what he showed us. If you pay attention, the information is there. AS: The CIA is frightening. I mean the more research I did the more frightening it becomes. Project MK Ultra is just one small part, that by itself is totally insane.  MK-Ultra. 2008. Screenprint and spray-paint on US Army issue t-shirts, pvc pipe, astro turf, carrying case, 36 x 22 x 86 inches. Accompanied by signed, first edition, Hardcover Mk-Ultra Handbook. GW: I'm interested in those installations as well. It seems like people aren't as familiar with your installation work. Could you describe them for me and why you made the choices you did. Because they are pretty reduced and they don't make, in my mind, as much sense without the text. What are they about? AS: Part of doing research is, the more you dig the more you find. I kind of wish that I didn't need to present the text because everything is there if you dig enough. GW: So, is it like the drug recipes in the Off the Grid series? You are presenting the ingredients of the recipe? AS: Often times I choose objects, like buy objects on eBay specifically because I want to put them in a painting and I would research a hundred different nutmeg tins, the year this nutmeg tin is and what state it was from, why that could be significant if you Googled those things. Every detail. And I almost feel like some of my paintings have hyperlinks in them. You know back in the old, early days of the internet you would click on an object and it would take you to a page of information. A lot of my work has hints or clues in it that hopefully open up new things. GW: Offers a lot for future art historians to chew on. AS: Yeah, it's a riddle. That piece, the MK ULTRA, the two soccer teams, the MK ULTRA installation was a really fun piece to do. And it came sort of organically together while I was doing research for the still life paintings for that Off the Grid show. GW: That was around the same time? AS: Yes, 2008. I did publish a handbook that goes along with the piece so there wasn't a need for a compendium of research or objects or back story of the piece. And at first I wasn't sure that I wanted that to be necessary to the piece, but installations are interesting to me because they are more of a gift. It is pretty hard to sell an installation unless it is fairly self contained. GW: Which you did with these installations. They're in military boxes. AS: There was an idea that the whole thing could break down and fit into a box and then be transported and be reassembled back into an army. Into two armies. GW: Which is what the military does really. AS: Yes, and that, conceptually, was part of the piece because living off the grid is about being self sufficient and breaking it down into the bare essentials and having those so figured out that...you're a survivalist. You have everything you need in a box. GW: Nomadic, it is a whole different way of looking at reality. Essentialist, being light on your feet, I guess. AS: But the idea that you have these two groups who were interested in the mind and altering the mind and controlling the mind, using the mind in certain ways or opening up the mind or closing the mind. They were basically interested in very similar ideas from opposite angles. GW: You are talking about the Millbrook piece and MK ULTRA? AS: Yes. GW: So, I didn't get that. They were actually made at the same time, representing two soccer teams? AS: They were made at the same time and were exhibited facing each other on two strips of green Astroturf. They sort of faced off. There is like this hooligan aspect to soccer and soccer thugs... GW: There is also a kind of refinement. AS: Exactly, it's like a beautiful chess game, it's called the beautiful game. It is international, the most played game in the world. In the U.S. we tend to be, and I played soccer growing up, and in a way I feel like it opened my mind culturally to what was going on in the rest of the world, because in the U.S. you realize that when you go out of the country, how little we know what is going on in the rest of the world. GW: It is very insular. That is one of the things that blew my mind when I returned from Australia. First there was the infinite amount of mundane choices you had to make, and second, that all you saw was the United States, all you heard about. It was mind numbing. AS: And then when you go spend time in Australia and you hear about all this other stuff going on and then you come back here and you don't hear about it at all. You're like, what's going on! So soccer as a metaphor for weird sport that could culturally open, I mean it did culturally open a lot of the brains of kids kids I knew from the time I was in Kindergarten. GW: They wanted to watch the World Cup? AS: They wanted to watch soccer made in Germany or PBS because it had soccer on every Saturday, you know something other than what we're fed. In a way it probably influenced me to look more seriously at studying art. Not doing what everyone thinks you have to do. GW: May be gave you a little push? AS: In finding out about other places, traveling, asking questions. GW: You said your dad was a professor? AS: Yes he was a professor. He retired recently from being a professor of pharmacy for 35 years. GW: Where was that? AS: At Oregon State. GW: You grew up in Corvallis and were born in Alaska... AS: I spent a little time in California before we moved to Oregon. Most of my family is from Northern California, the Bay Area. GW: If your dad was a scientist, I would assume that he is a pretty inquisitive person and interested in pushing boundaries? AS: Yes, well he was always...you know it's interesting, he was a professor of pharmacy that I think deep down inside may be should have been a professor of English. He was incredibly good at what he did and won professor of the year a bunch of times, he is actually being honored as an icon of pharmacy, but he always had this sort of romantic idea about writers. GW: Was he an influence on you to study writing? You still write. AS: I still write some. Before I moved to New York I wasn't sure if I wanted to move there as a writer or a painter. I wrote some plays in college and short stories. I love reading good writing. I think art always came more naturally, they say writing is the hardest thing, that you stare at the blank page until the beads of sweat turn into beads of blood, something like that. Writing is something I love but it is really hard. GW: Yeah it can be. The more you do it the easier it gets. Not totally, but... AS: I like writing and I like reading good writing. GW: Who is someone you would point to as an example of a good writer? AS: Céline is amazing. He wrote, Journey to the End of the Night. He is sort of an extreme example. He was sort of an angry writer but...Joyce is amazing but I also love Raymond Carver, very human...Bukowski. GW: These are people, in my mind, that seem to have a similar approach to their writing as you do with your painting. AS: Yeah that's probably true. Tim O'Brien and Denis Johnson I like a lot. GW: Total reduction of a thought. AS: Well I think studying writing and the writers that I was interested in...I think about painting in very similar terms to the way I thought about writing. GW: I noticed that about your work. That you use a very specific visual language, well not specific, may be precise. AS: Developing a character, when you are writing a story, too, you can tell more about a character by the way they stamp out their cigarette, or the brand they smoke. GW: The details. You were talking about that earlier. There was a time in my life where I felt that that is how I survived, just going from detail to detail. Walking through life, noticing things. AS: Yah, it opens up, and is also really kind of hopeful, this idea that may be there is something amazing that we are about to discover that is just right there. You could have walked right by it, but if we pay enough attention we might see something amazing. It's a really exciting idea. GW: It reminds me of, I don't know why, but it reminds me of this thing Baudrillard said. He talks about the "New Nihilism" where there is no meaning but that it is positive for him because you can make your own [meaning] and discover your own things and possibilities. Maybe he was following Heidegger? AS: Yeah, Heidegger talked a lot about an everyday way of existing and that we are thrown toward death from the time we are born obviously, but most of the time we are sort of in this fog. Every once in awhile we peek above the currents and see what's going on. GW: When we see one of your paintings. AS: Well, hopefully. That would be great if that is the case. That is something that I strive for I guess... GW: So, are you trying to make people uncomfortable? AS: In a wonderful way. GW: Because you love them. AS: Yeah. GW: Sometimes I think that telling people the truth or shaking people up can be an act of love. AS: I think pushing people outside of their bubble is exciting for them and exciting for me, hopefully. I remember, and this is kind of a weird story, but do you know about Burning Man? GW: Yeah, I think half of the City of Portland goes to Burning Man. AS: Yeah, Yeah, I forgot where I was [Laughter] AS: Yeah, I forgot where I was. Well a long time ago some friends of mine and I were there and we had this weird little plywood ramp for loading stuff off of this truck. We had all of this stuff on this truck. It [the ramp] was about six inches high, and we put it right outside in front of our tent and we put a sign next to it that said, "Ramp of Death". And we started yelling, "Dare to ride the ramp of death!". And everyone is on a bicycle there, so people started jumping over it and you know, its the most ridiculously small, non-death defying ramp you could possibly imagine. And all these people started lining up to jump over it, and the line went back, and people got so excited about it. GW: They made it over and kept going. AS: Well, everyone would cheer when they went over it, and then someone would crash, and then two friends of mine would rush over and pretend to bandage them up and it became this big performance. Then this little old woman came on. I don't know what she was doing at Burning Man, she looked like she was having a great time, she was probably 65 maybe, sort of looked...probably didn't ride a bicycle very often but was having a great day and it was a beautiful day and she was determined to ride over that ramp. And you could tell that she'd never done anything like that before. She probably hadn't ridden off a curb. GW: A bit terrifying. AS: It was terrifying but exhilarating and she made it over. Everyone cheered and gathered around her and it was just so...it brings tears to your eyes. Like, wow, what a big thing out of a small thing. To challenge someone or push them outside of their normal way of doing things. It's really powerful, so if I can do that with my work, that's something that I would feel really good about. GW: It seems like you already have. AS: Working on it, working on it. As long as people spend a little bit of time with it, which it seems like they are. It's fun seeing people, its fun spying on people looking at the work. GW: That is the great thing about being a visual artist. No one really knows who you are or what you look like. AS: Yah, I was there with my family today and they were going around and kind of watching people and they were saying, "Do you think anybody knows who you are?" No, nobody knows who I am. GW: I like that. AS: Yah, It's good, it's good...I don't know if we said anything intelligent, here, but I think we had a good conversation. GW: That's what I care about. AS: Yah, that's good. But there is a lot of work in the show [Disquieted] that I really like. It's exciting to be showing along side of some of those people. Su-en Wong I have known for a long time, she's kind of a friend of mine, so that was cool to be in a show with her and other people, whose work I have known for a long time, its pretty awesome. GW: When you admire someone and then all of a sudden you are put in the same place it is a very strange feeling. AS: It's pretty exciting. GW: Who was it...I think it was Sting. He talked about the first time he heard one of his songs in public. He got into an elevator and he heard his song in the elevator for the first time and he spoke about feeling like his mind had been blown. To be in a random elevator and hear some song he wrote. AS: It's just as exciting with the internet too. I have had my web site with my work on it for 10 years now. But it is always amazing to me when someone emails me from who knows where. I had someone email me from Turkey recently and they wanted to ask me some questions about painting and had a reaction to my work. And a strong reaction. It is just exciting when your work is out there. I mean it's exciting in a physical place because then people can interact with it in the way it is intended, but online it's exciting too. GW: I think your work stands up online, but I found myself wishing that I could stand in front of one of your paintings because I saw an installation view and they are actually enormous. They're big. AS - Yeah some of them are really big. The scale does make a difference. GW: Almost to scale or larger than... AS: Some of them are larger. The largest I work is six feet by six feet, so some of the elements are larger than life. It's nice when a painting sort of engulfs you when you stand in front of it. GW: I went to the Guggenheim when I was in New York awhile ago and saw the Ad Reinhardt show, the Black Paintings. I don't think I had ever experienced that level of visceral response to a painting. Did you see that show? AS: Yes. His work you've got to see in person. A reproduction, no matter how well it is shot, just isn't the same. I remember when I first moved to New York, I read Jackson Pollock's biography on the plane, and I went to the Museum of Modern Art and sat in front of one of his paintings. It was one of the first things I did when I got there. I stood in front of it and then sat in front of it for like an hour and a half. Just sort of soaked it in. That was amazing, amazing experience, coming from... GW: Rural Oregon. AS: Yah, all of the sudden, just being in New York where all this was happening. For the first month or two, even longer, I was in New York I would just be walking around like, I can't believe I'm here. GW: New York, my experience of it, is it's kind of like being immersed in a Jackson Pollock painting. AS: It is a special energy there. It's like history is happening around you. You really feel that way. Which is exciting. You ask yourself, "How do I become part of this history?" GW: Did you go on to study after your Bachelors? AS: I didn't. I thought I would. I went and I researched a lot of schools. I moved to New York and I ended up getting a job as an art handler for a little while, was researching schools and looked at a bunch of different schools in New York and RISD and some others. I just kept finding that people I was meeting, I met a lot of painters in New York because I really wanted to get out there and meet other people. I was really excited to be there. GW: People you had read about? AS: People I had read about or just people like me who had come, I was really determined, I just wanted to paint and I just wanted to do it. And I wanted to meet other people who were doing that and I did and it was really exciting. I went to these grad schools and I would meet the people who were there and they weren't as exciting as the people I was already interacting with so I decided that New York can be sort of a grad school on its own as long as you're disciplined. GW: I have had the same experience here. I did one year of art school and came back here and all of this stuff started happening. AS: Portland has a good art scene too and a great music scene. GW: There are a lot of opportunities here, if you have an ounce of motivation and energy you could pretty much do anything you want. AS: And you can make something happen here. GW: Yes, that's what I mean. I have organized projects like that, with hundreds of people involved. Real estate brokers seem to be a lot more interested in working with artists here. For one project (Step Into My Office, 2007) I got a 5000 square foot office space, for two months, for the pro-rated price of utilities which was around $400. AS: Wow, that's amazing. That's smart though because when the artists come the money comes. I remember when I first moved to New York I moved to Williamsburg, which is now like a...playground of hipsters. But at the time, I got held up at gunpoint my first night there, and the dumpsters were on fire, it was a scary place. There were probably 20 artists, 25 artists that started living there making it what it became. GW: That's how it happens. AS: That's what is exciting about New York is that even though its such a big overwhelming place in some ways, it does have a lot of people making things happen and sort of a DIY aesthetic. Like in Brooklyn people are doing stuff all the time. GW: I did a project with Flux Factory (Long Island City, NY) before they closed down. AS: Yah. Mm Hmm. GW: That was really fun. It was for one of the last things they did before they lost their building; did you hear about the, Going Places Doing Stuff, series? AS: Yep. That's awesome. GW: There's a lot more money there as well, so if you start going, and people see that you are committed...I mean they [Flux Factory] got money from the Andy Warhol foundation. AS: There are people who want to support artists [in New York], It's a lot more expensive in a lot of ways, but there are people who, that's exactly it, once you get going and people can see that you are committed they want to help a lot of times. So it's just a matter of getting momentum and staying afloat, and making it work. Beating the system. GW: This is one of the last questions I have, I know that we have been talking for quite awhile. It seems, as I have been reviewing your work, that a lot more installation and almost performative video or performing for a camera, is emerging. At this point we are interrupted by a woman collecting petitions. Petition Lady: Are you Oregon voters? AS: I'm not GW: He's not from here. Petition Lady: Are you registered to vote in Oregon? I have a petition to get sex offenders longer sentences, first degree rape, first degree sodomy, repeat offenders. It increases it from 70 to a 100 months to 300 and 90 days for driving under the influence. We are just trying to get it on the ballot to let everyone vote on it. GW: Are you going to be around this area? Petition Lady: Yeah, I got a couple other ones too. GW: Well we're right in the middle of an interview, so... Petition Lady: Oh! Ok, sorry. GW: That's Ok. Petition Lady: Thank you. The woman walks away. GW: Um...I'm specifically interested in, Potato Gun With Video Demo (2008). What was that about? AS: That kind of came out of the Off the Grid show survivalist, DIY sort of thing. GW: It's a potato Bazooka! AS: There is also an element of humor in a lot of my work and absurdity and the embracing of absurdity. GW: But it's kind of buried. AS: Yeah, It's an underlying, dark, absurd humor. The potato gun grew out of the drug recipes ideas in some ways  Potato Gun with Video Demo. 2008. Pvc pipe, krylon fusion paint, bbq igniter, aqua net hair spray, potato, stickball bat ramrod, custom rack with 58 second demonstration video 56 x 14.5 x 8" GW: Because it is something you can make at home with PVC pipe and hairspray. AS: Yes. You can make something ridiculously dangerous in about half a day, $40, and going to Home Depot. Which is just the way you can order opium poppy pods online for flower arranging and make opium tea. GW: I know someone who does that actually. AS: A lot of junkies do it to get off of heroin. It works, and it's, you know. This kind of mad scientist idea too in a way, I spend a lot of time in this 7 foot by 17 foot cement room... GW: Bunker. AS: Bunker, Yeah. Making paintings. GW: Are there windows? AS: Not in my studio right now. You know I researched, the more I researched the Unabomber the more I realized that I'm this crazy guy in this room that makes weird objects and has weird schemes and plots to take over the New York City art world. It's sort of similarly insane in a lot of ways and when you don't leave your studio for two weeks at a time and sleep on an army cot, which I was doing for awhile, you do get a little crazy. When someone calls you on the phone sometimes you can't even talk. I mean, do you experience that? GW: Over the last six years I have had to work with people because that is what I have been doing, interacting and organizing people, but I know what you're talking about. AS: The brain changes and that change is interesting too, it's chemical, but something happens when you're doing a certain task over and over again, the other parts of your brain change. GW: A friend of mine has this theory based on her research into neurology. If you do something 10,000 times, the same action 10,000 times, your whole brain lights up when you do that action, it completely turns on. Like enlightenment. AS: That's probably why I like doing this so much [holds up his finger] I got a good bump right there from holding the brush. GW: A painting callous. That's amazing. AS: At the very beginning of this conversation we started to talk about the video work and I sort of got off track, but you were saying you liked the lo-fi aspect of it. You know, when I started out doing that video piece I knew what I wanted. I had a picture in my head of what it could be, but I didn't have much technical experience. When I was a kid I made weird, funny horror movies, when I was 12 or 13, on VHS camera. GW: Do you still have those? AS: My friend probably does somewhere. I should get a copy. We just wanted to do it and figured out a way to make it work however we could do it. That is how I approached this video. GW: I learned a long time ago that limitation is the best friend of creativity. That is how I operate. I will use computer programs that other people would scoff at to do video work and sound, I do music too. AS: Yeah. Give yourself a problem and find a way to solve it. That's the process. Use whatever you have at hand. Otherwise you just end up making excuses why you can't do something. GW: Or resorting to gimmicks. Put 17 Photoshop filters on it and call it good. Too many possibilities. No restraint. AS: Part of the magic of making something is that you don't know what you're doing when you're doing it and you end up with things that you never set out to do, but the real choices are whether you keep them or get rid of them. It is the reductive process of painting. What marks you leave, what marks you get rid of. Editing video is very similar to the painting process. GW: Especially the way you describe it. Cutting it back, taking stuff away...Wow, we have been talking for 76 minutes. AS: you have your work cut out for you. All images used by permission of the artist. Posted by Gary Wiseman on May 14, 2010 at 15:32 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |