|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

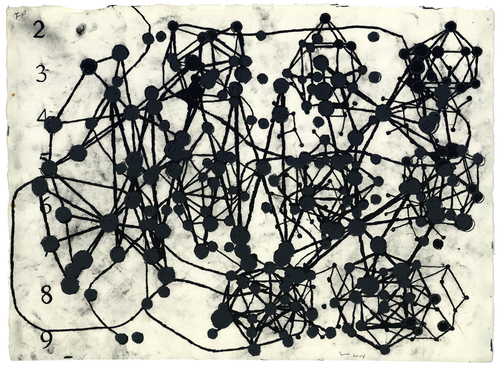

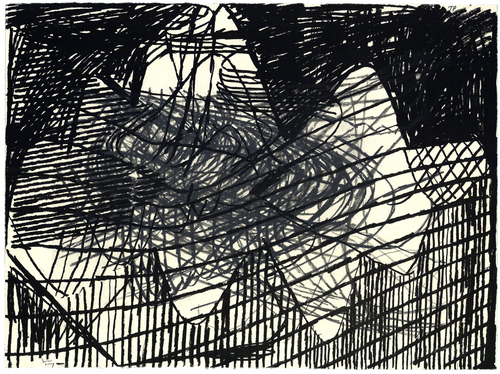

Terry Winters at Reed College  Terry Winters, Bond (2004) When you walk into the excellent exhibition of recent prints by Terry Winters at Reed College's Cooley Gallery, you are confronted by a remarkably consistent body of work that is the product of both a sustained rigor and an unflinching critical thought. Winters's work is a complex, evolving fusion of material and image while refusing to allow itself to be only defined as one or the other. His recent work often includes a series of self-generating forms that he describes as knots. The knots often intertwine with one another so that positive and negative space merge to create new kinds of forms with are in turn explored and expanded with additional layers of information. These forms serve as a guide to the pictorial and critical transformations that guide the intent behind most of the prints in the exhibition.  Terry Winters speaking at Reed College It was interesting last night when Winters started his lecture at Reed College by talking about how his work often starts with things that are external. His sources often include things like images, diagrams, or forms. The sources are then remade, explored and transformed during the his process of making the work. It is not until those forms are reworked that they begin to have an internal resonance for him. Like an alchemist, the external is reworked until it has an internal significance. He also talked about the importance of the idea of the signal to noise ratio to his work where the relationship between the coherence or legibility of the image is challenged by the natural properties of the materials that are used to make the work. Most art is about illusion and making someone think that something is one thing when it is really something else. Winters doesn't hide anything in his work. It is all right there on the surface. Whether it is a smudge of graphite or the roughness of a brush stroke, everything is allowed to be according to its character. The nature of the material is allowed to come through to challenge and expand the image. He often works from sources that might be drawn with the precision of a computer but when he redraws it there is an incredible coarseness and tactility to his work. His images are made by hand and you can feel it.  Wave (2004) You sometimes get the feeling that the smoother and more perfect the image is, the rougher Winters is going to be when he is reworking it. It is as if he is asking that if one thing is true about an image, is the opposite equally true? Would it still be true if you layer something else on it? And what would happen if you layer something on it again? He is breaking his source material, reconfiguring them and splicing them back together again creating a hybrid synthesis of image and material. The work is an exploration of line or color or pushed into new spaces. His work is never about any one thing. It is a multiplicity, an unexpected totality all at once. Someone asked about why his work is never about any single image, idea or form; it is always layered or challenged and why is that act of negation important to the experience of the work? When I was thinking about the question I realized negation has certain associations like erasure. You erase something because it does not work or it is not what you expected. It implies you are judging and evaluating, an act that is only possible if you are outside of the work. His response to the question was very clear. He said it wasn't so much about negation as it was another way of exploring the potential of the work. If he erases something, it is not as much about erasure, as it is drawing by subtraction. His process is additive. One of the most important things about his work is that he doesn't stop. He doesn't stop when a form is beautiful or there is a jarring juxtaposition of diagrams. He doesn't stop when the work reaches some preconceived idea about what the work should be. He is able to get himself outside of work. It is as if the work has a life and language of its own and he just tries to help it along. I think that is an incredibly rare quality in an artist. The result is that when you are looking at the work, you are free to inhabit and explore the worlds that he creates for you on your own terms. Terry Winters: Linking Graphics Prints 2000-2010 Reed College, Cooley Gallery January 26- March 7, 2010 Posted by Arcy Douglass on February 26, 2010 at 9:00 | Comments (15) Comments "He doesn't stop when the work reaches some preconceived idea about what the work should be. He is able to get himself outside of work. It is as if the work has a life and language of its own and he just tries to help it along." Arcy -- I don't mean to pick on you, but this passage jumped out at me and I am compelled to comment: All artists worth their salt work this way. You start a painting and there is a certain dynamic; much of the rest of your work is the close listening necessary to discern the form suggested. Or, to be a bit less simplistic, there is a give and take. This is true whether you are Winters or (forgive me) Chardin. Okay, I have about three thoughts and now I have foisted two of them on you. I can't remember the third; maybe your next essay will shake it loose and then my work here will be done. Posted by: rosenak Sure, I think that statement is true of many successful artists but to put it back in the context of the entire essay Arcy is making a case for Winters as a remarkably procedural painter. He starts with source material and through a very rational process investigates how in his words, "open up" that source material. Recently that has been a series of knots... and in an alexandrian turn he's trying to cut those gordian knots. Is he a more procedural painter than Chardin, hell yes... because he's all about the process and investigation to the point that he sometimes sacrifices aesthetic satisfaction to the process. Chardin was much more interested in pictoral harmony. In that way Id say Winters is most related to Cezanne but he's even more extreme (being very indebted to the post impressionist). Arcy is right to consider Winter's somewhat extreme though there are a few other painters like Kain Davie and Bernard Frize who share some similarities.... in the end though Id have to say Winter's is the one who tests his process the most on every single painting. Frize and Davie tend to test their process by changing the process from work to work, Winters works over a single painting more than those two. Each method has its strength but again, Winters is hardly like most painters... he's definitely an extreme example because he's so orderly and dedicated to the process. We could discuss Kieth Tyson, Sol LeWitt and Pollock too but they too are less true of Arcy's statement... though much more so than Chardin.

Posted by: Double J Hi Rosenak, Thanks for commenting. It is a rare thing for an artist not to get in the way of his or her own work. In Winters' case, he is letting his language evolve and present itself on its own terms. It is like we are witnessing a natural process except that it is in the physical forms of an artist's practice: drawing, painting and prints. I will still insist that it is a surprisingly rare experience to be look at an art work and not feel like you have to work through the artist to get to the work. When I look at Winters' work I feel the language but not the artist even though I know full well that there could not be the work without the artist. There is a difference. The best artists, like Chardin although there are of course other examples, make the work seem so direct and so straight forward that someone looking at the work is immediately given a new way of looking at the world. The work is self evident. I think that is what good art does, it keeps our perceptions of ourselves and the world evolving. Posted by: Arcy Yes, you're right that I pulled the passage out of the context of the whole essay; and, yes, we're comparing a matter of degree, but that was my point -- it seemed to me that Arcy was saying that this process makes Winters' work essentally different, and I was arguing with that. Sure, there are many other artists whose work is closer to Winters in that way, but that's why I used Chardin as an example (in both this and my last round of comments) -- his work is very different while still sharing the process Arcy describes. Posted by: rosenak I'm really not quarreling with your interpretation of Winters -- whose work I don't know; I'm arguing -- here and elsewhere -- for a way of looking at representational art that is less cut-and-dried than that which we are too-often taught is correct. Posted by: rosenak Okay, on second thought I guess I only have one thought! Posted by: rosenak Now we are getting somewhere. Let's start with the differences between representational and abstract art. When you paint a picture of a tree. It is a bunch of material on the canvas positioned to have a visual resemblance to something that we would collectively call a tree. The painting is not a tree. It is not tree and does not have anything in common at all with a tree. The painting is an illusion, a representation but never thing in itself. The painting is always separated from the subject matter. One could say that a representational painting is the opposite of the subject matter. An abstract painting on the hand, is exactly the subject matter. A circle is a circle is a circle. A brush stroke is a brush stroke. The painting is the subject matter. They are the same thing. It does not pretend to be an illusion of something that it is not. A Winters painting is exactly about the space that he is creating in the work at that moment. Nothing more and nothing less. This is a crucial difference. Now we know of painters like DeKooning that were able to operate in some sort of middle area but he had a very clear idea of the rules that he was playing by. If your question is can you update Chardin? I would have to say no. Chardin was Chardin and everybody else is everybody else. If De Kooning could not do it, there is no hope for the rest of us. Are the lessons that can be distilled from Chardin's work that would be relevant to today? Absolutely. A reinvention of representation would have to address the whole problem of illusion. If you address the problem, the painting is probably what we would call abstract. Posted by: Arcy "If your question is can you update Chardin? I would have to say no. Chardin was Chardin and everybody else is everybody else." What do you mean by "update Chardin"? If you are making a painting using something like his language, do you mean that the painting is necessarily about Chardin or about claiming a certain relationship? Or do you mean that because you are not Chardin (or anyone else) you must use a language that is entirely your own? "If De Kooning could not do it, there is no hope for the rest of us." Why? "A reinvention of representation..." Why is it a given that we need such a thing? "...would have to address the whole problem of illusion." Why do you call illusion a problem?

Posted by: rosenak No one can understand Chardin's language as well as Chardin did. Someone can not understand another artists language deeply enough to be truly innovative with it. If someone tried to use Chardin's language, they would be derivative and not as good as the original. They would be like a caricature. Also the artist would be missing the issue of context. Chardin's paintings meant something specific for his time. Our times are different. If you think otherwise, you are disrespecting the original artists work. Everyone has to find their own voice. As for the rerepresentation, that came from you: "I'm arguing -- here and elsewhere -- for a way of looking at representational art that is less cut-and-dried than that which we are too-often taught is correct." Posted by: Arcy I had an entirely different—and admittedly much more negative—take on both the show and the lecture. There's a portion of Gulliver's Travels where a university professor has spent his whole life designing, building and operating a giant press for cucumbers on the theory that if sunshine is necessary for things to grow it must therefor be possible to squeeze sunshine out of cucumbers. Winters strikes me as a master of the sort of academic kabuki that uses the library of aesthetic theory to disable critical objection. That he's not hurting for an audience or for recognition says he must be doing something right, so that's fine and good for him. But I was like Gulliver at that lecture: nodding in appreciation, declining to get involved, hastening out of the room. Posted by: Hg "No one can understand Chardin's language as well as Chardin did. Someone can not understand another artists language deeply enough to be truly innovative with it. If someone tried to use Chardin's language, they would be derivative and not as good as the original. They would be like a caricature." As I understand it, here you are saying that -- even though people can understand each other well enough to be moved by the art others make -- we must nevertheless be entirely original in our artmaking because other people are hopelessly other. (If an imperfect understanding of others is a problem so severe that it prohibits speaking the same language as others, why presume to make art at all?) Too slavish imitation results by definition in bad art, but you can speak in someone else's language and be original enough to make live art, or should we quit speaking English because others -- others we may not entirely understand -- have made it their own? "If someone tried to use Chardin's language, they would be derivative and not as good as the original. They would be like a caricature." Would you substitute your favorite English-speaking author's name for Chardin's and say the same thing? "Chardin's paintings meant something specific for his time. Our times are different. If you think otherwise, you are disrespecting the original artists work." No, I am agreeing that we cannot hope to understand his work exactly as he did and I'm asking why -- if that is prohibitive -- the same thing wouldn't apply to all art made by others. If we are incapable of fully understanding a piece of art in the same way that the artist does or did, and it is disrespectful to regard it any other way, shouldn't we just gouge our eyes out? Posted by: rosenak Arcy -- If you aren't too bored or annoyed by this, I'd still like to hear what you mean by "the problem of illusion." In any event, thanks; it's been fun. -- David Posted by: rosenak Hi David, The question of illiusion is probably one of the biggest issues that drove 20th century art. I am little worried that we are going off topic and a proper response would require more time and space than I have here but I will say that illusion is the enemy of the present moment. Let's talk about one of Chardin's still lifes. Today,when we talk about the painting we might look at the composition or the technique or simply that they are beautiful. All of which are true. However, if you were to walk into the studio when he is making one of his still lifes, I would be surprised if you or anyone would barely be able to breathe let alone talk about any of the issues that we were talking about the painting. I assume that you have come across rotten meat at some point in your life so that you would know what it smells like. I assume that there are worse smells but none come to mind at the moment. It would have permeated his studio and everything that he would have come across. I wouldn't be surprised if there are accounts that Chardin began to smell like the meat in his studio. You can't escape it. If the smells of the studio were probably the dominant sensory experience in the studio why is it, thankfully, not accessible to us? It is because a representational painting is a window into a world that is not available to us, ever. A representational painting is a window into a world that we can see but never participate in, never move around in or see change. It is static, fixed perspective, mono view from one view from forever. It is never real and the more it tries to present itself as real, the less real it becomes. For whatever reason, up until the 20th century, it seems like the focus of western art was to separate the viewer from the subject matter. The paintings are windows, separated by frames so that we are looking into a space rather than participating in it. Our scupltures come on pedestals to make sure the space of the sculpture is not interfered with by the the space of the room. This a uniquely western approach. The Chinese did not separate viewer from subject, nor did the Japanese, or the Africans or the Native Americans. I wonder if the problem of illusion even exists outside of a strictly western approach to art. Is the obsession with illusion about some sort of intellectual distance or some sort of Victorian idea about art appreciation? Now you might say the question of illusion is more than just representational painting. The same thing applies to scuplpture. Look at a sculpture by Rodin, let's say Balzac. When I am standing in front or walking around that sculpture, we exist in two entirely different worlds. Mine is dynamic, variable and not defined by a pedestal. His is although it might be rather larege is nonethless defined by the pedestal on which it rests. There is nothing for me to participate with in that sculpture except in a visual,read western, way. There is always an insurmountable gap that cannot be crossed between my world and his. So far we have discussed the ways that illusion separates the viewer from the space of the work. I want to elaborate on why illusion is also a rejection of the present. An illusion is only successful if it makes somebody believe something that doesn't exist. There is a basic agenda in that statement, illusion is trying to direct the attention or the focus of people who interact with the work. An illusion is the opposite of having people figure things out for themselves. With illusion, viewers are by definition directed, solicted or fooled. Do we really not trust ourselves that much? There is also a potential darker side to illusion with things like propoganda, advertising and politics. Once you start manipulating people where does it stop? I think that Winters work provides an interesting commentary on illusion here. I have referred to his work being coarse. The coarseness prevents an coherent reading of the illusion of space. After the pencil or brush stutters the illusion of space is destroyed. So what initially looks like an issue about craft or technique is really about the deeper issue of illusion. Of course, that also opens up the possibility that it could be slightly exagerated or mannered. Works could be made deliberately rougher to prevent the image to be stronger than the material than something made by someone with his skillset would suggest. Posted by: Arcy Thanks. Would it be fair to say that your objection to illusion is that it cannot deliver truths? I would again respond with the analogy of spoken or written language. The words "rotten meat" fail as rotten meat, but they can be very suggestive, especially when combined artfully with other words. You might not be able to clear a room with them, but you can convey something truthful about the rotten meat experience. Was Chardin trying to deliver the "dominant sensory experience in (his) studio" or was he trying to convey something broader about life through suggestion and evocation, something he would not have been able to get across by simply displaying a plate of past-date venison? "(A representational painting) is never real and the more it tries to present itself as real, the less real it becomes." This would be a problem if a representational painting depended for its effectiveness on convincing the viewer that it is not a painting but an actual piece of meat. We can safely assume that the artist intended no such trickery because an actual piece of meat would have been so much more effective, not to mention easier to produce. In fact, the opposite is true: the effectiveness of representational painting depends on your awareness that it is a painting, an illusion, an object constructed to speak through allusive means. This is not "separat(ing) the viewer from the subject matter" (nor is it "some sort of intellectual distance or some sort of Victorian idea about art appreciation") because the nominal subject is only a vehicle for opening the viewer to a larger awareness (that's how the good ones work, anyway). "There is also a potential darker side to illusion with things like propoganda, advertising and politics. Once you start manipulating people where does it stop?" That's true, but if that's an argument against representational painting it's an argument against speech. "An illusion is the opposite of having people figure things out for themselves. With illusion, viewers are by definition directed, solicted or fooled. Do we really not trust ourselves that much?" Why do you write, then? Posted by: rosenak "An illusion is the opposite of having people figure things out for themselves." This is no more true of illusions than it is of experiences, stories, or dreams. Posted by: rosenak Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)